A stigmatizing discourse that paints the press as the enemy and the impunity that reigns over attacks against journalists are the main factors that have made possible the climate of violence experienced by the press in Ecuador in the last two weeks, in the midst of a national strike in that country.

This is the opinion of several freedom of expression organizations that have condemned the wave of attacks in several cities of the country during the demonstrations, called on June 13 by the Ecuadorian Indigenous leadership and other trade organizations.

Demonstrators demand that the government of President Guillermo Lasso lower fuel prices, cancel debt of Indigenous peoples, set fair prices for agricultural products and increase the health and education budgets, among other demands.

"There is a very serious climate of violence against the press. There have been violent incidents, such as attacks with stones, sticks. Journalists are thrown objects or boiling liquids, they are not allowed to do their coverage," César Ricaurte, director of the organization Fundamedios, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "There has been overall violence in the context of the strike. It has been something permanent, systematic and widespread."

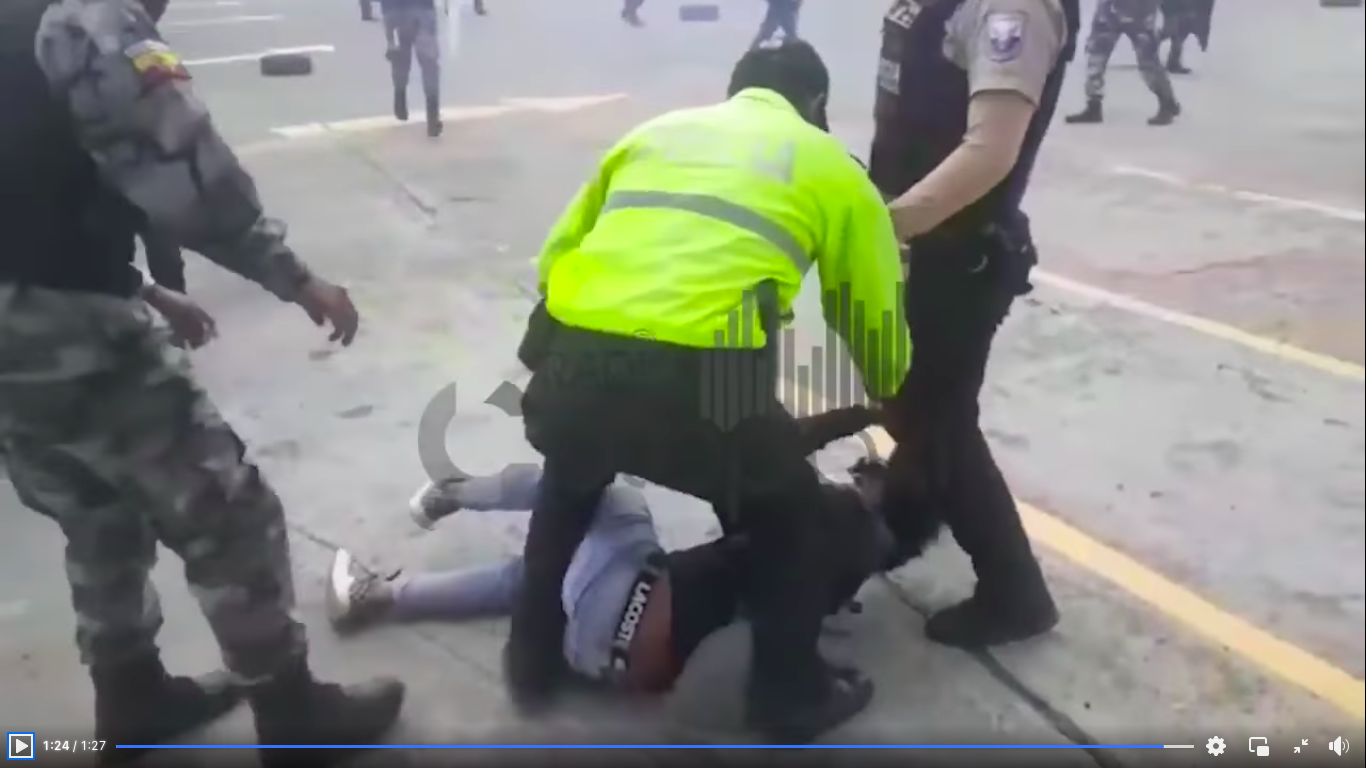

Videos circulating on social media show various attacks on journalists by demonstrators and law enforcement in several cities in Ecuador. (Photo: Screenshot of a Facebook livestream)

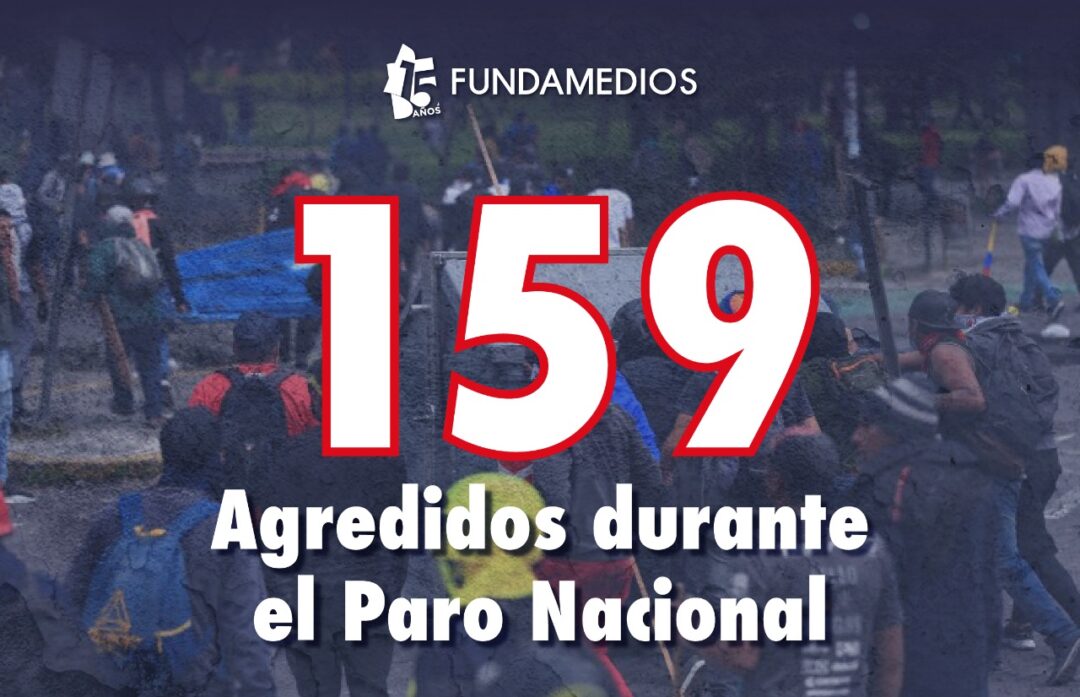

As of June 28, Fundamedios had registered a total of 142 attacks on 159 victims, including journalists (86), camerapersons (27), photojournalists (9), news outlets (8), journalists (5), assistants (4), websites (4) and human rights defenders (4). Eight of the aggrieved journalists were attacked more than once.

The organization revealed that in 117 of those violence cases, the aggressors have been demonstrators; in 14 cases, the security forces; in 13 cases, unknown individuals; in 6 cases, public officials; in 4 cases, non-state aggressors; in 4 cases, political figures; and in one case, an Indigenous leader.

The most frequent attacks have been physical aggressions, with a total of 65. There have been 49 threats, 17 cases of stigmatizing speech, 10 cases of preventing access to information, 6 cases of restrictions in the digital space, 5 cases of equipment theft, 4 arrests, 2 cases of destruction of equipment, and a case of substandard legal process.

The recorded attacks have taken place in the provinces of Pichincha, Guayas, Cotopaxi, Bolívar, Pastaza, Imbabura, Morona Santiago, Napo, Chimborazo, and Zamora Chinchipe.

"The attacks come mostly from demonstrators who accuse the media and journalists of being biased political actors in the national strike called forth by the Indigenous movement," the regional network of organizations for press freedom and protection of journalists Voces del Sur said in a statement issued on June 23. "[...] All this is happening in the midst of a constant discourse of rejection of the presence of journalists and a stigmatization of the work of the media."

"Corrupt press" is one of the slogans most often repeated by protesters in their verbal attacks on media staff. This phrase was popularized by former president Rafael Correa as part of a smear campaign against journalists and news organizations that he waged during his 10 years in power through official radio and television outlets.

This stigmatizing discourse that portrays a press at the service of the government or other sectors of power has spread to social movements, such as the Indigenous movement, which is leading the current national strike.

"If you listen to the speeches, the factor of the press as an enemy is always present. This is something that regional and community leaders also deal with. If one were to review the speeches of the Indigenous leadership, one would see that there is a generalized discourse against the press," Ricaurte said to LJR. "This justifies [their actions]: 'This is legitimate because the moment I attack a journalist, I am attacking the one who is supposedly my enemy.’"

On several occasions, leaders of the Indigenous movement have prevented coverage of their mobilizations under the idea that the traditional media in Ecuador do not tell the truth and do not fairly reflect their voices. According to the director of Fundamedios, there is the notion that if the press does not stick to the truth of the Indigenous leadership, then they are enemies.

Fundamedios keeps a record of the number of attacks on members of the press since the national strike began on June 13. (Photo: Fundamedios)

"There are news outlets that are very critical of the Indigenous movement, of these mobilizations. But even those outlets have the right to carry out their coverage and to do their work safely without being subjected to aggressions and conditions in which they are not allowed to do their work," he said. "That is part of the democratic game, the existence of different editorial lines and that is what feeds the plurality of the media environment."

The Red Voces del Sur network reminded the leaders of the national strike that journalists are not political actors and that their job is to gather all the voices so that citizens can learn about the diversity of events.

"We condemn these aggressions and urge the State and the social organizations that promote the mobilizations to provide due protection and guarantees to carry out journalism and thus acknowledge the importance of the work of the press and journalists in these contexts," the organization said in its statement.

Impunity in cases of violence against the press in previous years is another factor that has encouraged attacks during the current national strike.

In October 2019, Ecuador was the scene of serious aggressions against media outlets in the midst of another series of demonstrations. Among the most serious cases at that time were the attempted arson of the Teleamazonas channel, holding down a group of journalists by demonstrators and the attack against journalist Freddy Paredes, who was knocked down by a stone in the head that sent him to the hospital.

Ecuador's Public Prosecutor's Office only investigated Paredes' case and sentenced the aggressor — a temporary employee of the Ecuadorian National Electoral Council — to four and a half months in prison and to pay a fine of US $2,000, which he did not pay, according to the newspaper El País.

"There has been no other case that has been prosecuted or investigated. There is absolutely no exercise of justice, nor of investigating or punishing aggressions against the press," Ricaurte said.

Social organizations and international organizations fear that the wave of aggressions that began on June 13 could lead to a human rights crisis for citizens, mainly regarding their right to be adequately informed.

Amnesty International said in a statement published on June 20 that the criminalization of journalists and human rights defenders in Ecuador, as well as multiple reports of harassment and excessive use of force, "is causing a human rights crisis reminiscent of that of October 2019."

Journalists covering the protests have been attacked with stones, sticks, objects and even boiling liquids. (Photo: taken from Fundamedios Twitter)

On the other hand, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and its Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression (RELE) called on authorities and social leaders to avoid attacking or stigmatizing the press and recalled the importance for journalists to provide full coverage of demonstrations for the good of citizens.

"[...] The journalistic coverage of social protests, in conditions of security and freedom, is transcendental for citizens to access information and opinions about the claims from perspectives as plural and diverse as society itself," the organizations said in a June 24 statement. “Lack of access to information has the potential to affect both institutional and civil society voices, hinders social understanding of the environment and makes possibilities for dispute resolution more distant.”

The coverage that Ecuadorian citizens receive has also been affected, given the self-censorship that some journalists have opted for. Especially those who report on the front line and those who work for television media, to ensure their physical integrity.

"Television coverage is now from afar, teams are no longer located onsite at the marches but in places where they can zoom in or send a drone to take shots from a pedestrian bridge or a nearby building. But there is no longer front line coverage of the marches. And, obviously, this is a very reasonable self-protection measure," Ricaurte said to LJR. "There is a tendency to self-censor when covering the protests."

Although the active aggressors of the press have been mainly demonstrators and police forces, the State's inaction in the face of attacks and hostility to the press has allowed violence against the media to spread without major obstacles, according to the organizations.

"The State has not articulated sufficient actions to ensure the work of the press. This is in addition to the dangerous speeches of Indigenous leaders who, one day ask for respect for the press and the next accuse the media of sowing hatred and violence. This leads to the creation of an adverse environment for freedom of expression, press and access to information," Red Voces del Sur said in its statement.

For Fundamedios, not only the current government is responsible, but also past administrations of Lenín Moreno and Rafael Correa, during which there were no effective measures to protect journalists.

"The State is responsible by omission, in this case. In the decade of Rafael Correa, the government was the main aggressor against the press. But in the two subsequent governments, what has existed is practically complete inaction. No public policy for the protection and security of journalists has been adopted. Everything has remained in proposals, in truncated experiences, such as the creation of a committee for the protection of journalists," Ricaurte said.