Recently, Peruvian President Pedro Castillo met with a group of journalists from the Huánuco region at the Government Palace, in Lima. He proposed that they form their own press agency so they could receive state advertising money and that he himself would advise them, as published by the news site Sudaca.

The regional journalists then promised to provide "support for democracy," the site noted.

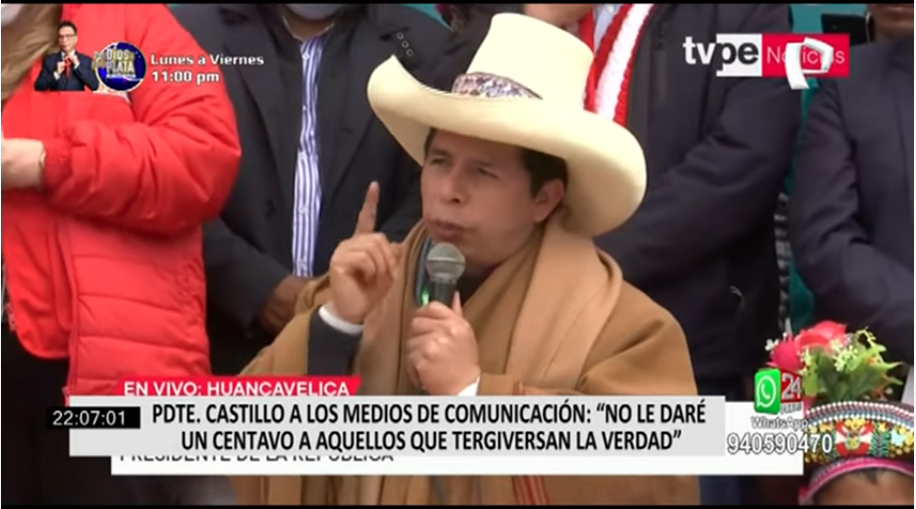

Days before, President Castillo, told media he would not give "even a penny" to those who misrepresent the facts, misinforming, as published by La República. Castillo alluded to the video posted by various media of a group of people who rejected the president shouting "vacancia" (meaning, he should be removed) while he had lunch in a busy restaurant in the city of Arequipa, stated the newspaper. According to the president, it was not a protest as some media had said, but rather just a few people screaming.

Peruvian President Pedro Castillo addressing the press. (Screenshot)

On Tuesday, Dec. 7, the Peruvian Congress voted for a moción de vacancia against President Castillo to remove him from office due to permanent moral inability to govern, for appointing ministers with alleged ties to terrorism, among other reasons. A majority of the voting legislators rejected the motion.

"What the president said was tremendously unfortunate, he took 10 steps back, giving advertising a political connotation again, when what is being fought for is that this is a purely technical issue," Zuliana Lainez, president of the National Association of Journalists of Peru (ANP, for its acronym in Spanish), told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "State advertising is the responsibility of the State and must respond to mechanisms that, from the State, promote the sustainability of a good media ecosystem."

Castillo also expressed his "gratitude" to the country's regional media, recognizing them for the work they do, because they know what the "great problems of the country" are, as reported by El Comercio.

"If you analyze the speech of the president and those close to him in the Executive branch, they have this dichotomy between the 'Lima press,' which harbors political interests, versus the 'regional press,' as the press that really knows 'the people,'” Rodrigo Salazar, executive director of the Peruvian Press Council (CPP), told LJR.

Adriana León, director of the area of freedom of information at the Press and Society Institute (IPYS) of Peru, described President Castillo's comments as "populist."

"Journalists from regions in the countryside work in very poor conditions, so the president's proposal is even more serious, because by asking them to commit to democracy in exchange for state advertising, they risk ending up serving as an echo chamber for his government,” León told LJR.

The skewed media coverage of the recent polarized elections in Peru must have created in the president an animosity towards the press, León reflected.

"Castillo as president does not speak to the press, does not give interviews nor does he open the door of the Government Palace to journalists" from Lima.

At first the ANP had its hopes up, when Castillo proposed the decentralization of state advertising in his inauguration speech on July 28, Lainez said.

“The state advertising distribution model in Peru must be reformulated urgently, it must be decentralized. Unfortunately, state advertising continues to operate under little technical criteria. It is not only this government, it’s been a criticism we’ve had of at least the last three or four governments.”

According to an article in media outlet Sudaca, after the government of Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000) and onwards, the investment of state advertising in the media decreased. Between 2005-2020, according to the study by journalist Jaime Cordero on which the Sudaca article is based, state advertising represents only between 2 percent and 8 percent of the total income of the country's large media, such as Grupo El Comercio, América TV/Canal N, Grupo La República, Grupo RPP, Latina and Grupo Expreso/Extra.

Since July of this year, Congress has been discussing a series of modifications to the Law that regulates State Advertising (Law 28874), enacted in 2016, in order to make it more equitable at the national level, as published by the state agency Andina.

The modification of Law 28874 would include criteria that consider the duration of the state campaign, target audience, coverage, informational balance, impact of the campaign, price, location of the media and validity of authorization from the Ministry of Transport and Communications, as appropriate, La República reported. This initiative, the newspaper said, also calls for prioritizing media from districts, provinces and regions with local programming that is at least 50 percent of the content.

State advertising, according to the Peruvian Congress, are all public resources that are disseminated in the country's media, public or private. These can be health, education, environmental, safety campaigns, etc. The formats can be photographs, video, illustrations, posters, radio spots, etc.

When a first draft of the proposal to modify the law was presented in 2019, under then-president Francisco Sagasti, the Peruvian Press Council (CPP) questioned, among other criteria, that state advertising be allocated on the basis of whether the media have been authorized by the Ministry of Transport and Communications. "This can be used as intimidation," the Council noted at the time on its website.

The CPP has always supported a more equitable distribution of state advertising so that it reaches more regional media, Salazar said.

“The problem in Peru is that we have no in-depth market study at the national level that really reflects the scope of digital, print, radio, and television media. Or sometimes it is known, through surveys, what is the reach of the media in Lima, but the reach of the provincial media is not being measured,” he explained.

According to Salazar, the CPP has proposed all along that this market research at the national level be carried out by the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), in collaboration with a private entity, every two years, to measure the readership and reach of the country's media by periods.

Lainez agreed with Salazar that surveys of the media's reach in the provinces are almost non-existent in some regions and that, consequently, they do not receive any advertising from the state. "Much of what we colloquially call ‘the advertising cake’ is destined to the big media outlets in Lima," he said.

State advertising should be a priority in those places where it is less sustainable for a media outlet to survive solely from commercial advertising, Lainez said, because they are located in remote cities, with little commercial activity.

“Geographic criteria should be incorporated into distribution issues. A rotation system for the assignment of advertising funds should also be considered, to fundamentally sustain media that generates local information. That for us is key and should be under discussion in the Executive branch," Lainez added.

It is urgent to have a broader debate on issues of state advertising and its allocation in the country, Lainez said. “We must remove the stigma once and for all that state advertising can be used to reward or punish editorial lines. That is terrible for democracy.”