Starting from the top of South America, they radiated out to the corners of the continent. From their homes in Venezuela to temporary havens in Colombia, Peru, Argentina and the U.S.

They are part of the 5.4 million refugees and migrants from Venezuela worldwide. But, they are also storytellers, and have found ways to create journalistic projects in their host countries to integrate, train or provide quality information to those who are going through migratory processes.

These projects have also meant for their founders a way to keep doing journalism and stay connected with Venezuelan events. Migrant status makes it difficult to legally practice the profession due to a number of requirements or conditions. According to a report published in 2020 by the organization Acción Contra el Hambre on the employment conditions of Venezuelans in Peru, “more than 80 percent of migrants work in unstable, insecure jobs and without access to any type of labor rights or social benefit.”

In this context, LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) spoke with the leaders of four journalistic projects born from and for Venezuelan migration: Capsula Migrante, Semillero Migrante, Sho Soy de Venezuela and Venezuela Migrante.

Cápsula Migrante

In April 2020, the founders of what would become Cápsula Migrante (Migrant Capsule) made a journalistic report for the digital media outlet Efecto Cocuyo of Venezuela about the first Venezuelan who died in Peru as a result of COVID-19. There, they realized the informational need that migrants had in that Andean country.

Hector Villa and Pierina Sora, founders of Cápsula Migrante (Courtesy)

"Before the pandemic, what the Peruvian media reported were negative aspects of migration, but when the mandatory quarantine arrived, that news focus disappeared and was not even considered, despite being a very vulnerable community that was quite affected by the situation,” Hector Villa, co-founder of Cápsula Migrante, said in an interview with LJR.

As a result of this, Villa, together with journalist Pierina Sora, decided to give life to Cápsula Migrante, a project that informs, listens and empowers the Venezuelan migrant community in Peru through videos, forum-chats and WhatsApp groups. Peru is behind Colombia as the second country with the most Venezuelan migrants in the world, according to a World Bank report made in 2020.

Every Monday, they disseminate brief, practical and verified information of interest to the Venezuelan migrant population in Peru and also hold forum-chats with specialists and trainings in various areas.

“The foro-chats have been very successful, people in the community like them very much, we have touched on topics such as migratory grief, healthy eating, how to take care of yourself in times of pandemic,” Villa explained. “Not everything has to be investigative journalism (which is very important and necessary for society) but we also need journalism that is attentive to these communities and provides them with useful resources. Above all, because they are in a process of adaptation.”

The founders of Cápsula Migrante consider that although there are many other accounts on social networks, with a large number of followers, dedicated to reporting on daily events, they are differentiated by their journalistic ethics and vocation to serve their community.

“When we migrate, we have many fears, especially that of growing farther from the profession. I know several colleagues –I was also like this– that during the day we had to work in a different area (bakery, masonry, security guard), and at night we had to be journalists ... With Cápsula, I can practice journalism and, in addition, it allows me to be of use to a community,” Sora told LJR when asked about his immigration experience.

Semillero migrante

Venezuelan photojournalist Fabiola Ferrero, currently living in Colombia, has been building the idea of Semillero Migrante (Migrant Seedbed) for a couple of years. The focus of her career has been migration, visually telling the experiences of those who leave and also the stories of those who remain.

Ferrero partnered with the Roberto Mata photography school and civil association Espacio Ana Frank in Venezuela, and the Ojo Rojo Fábrica Visual foundation of Colombia to create Semillero Migrante, a mentoring program for young Venezuelan migrants in Colombia and their local peers.

Participants in the Semillero Migrante project (Courtesy)

The program is intended to empower emerging talents to develop their vision as visual storytellers and to help them engage with local communities.

“Initially, it was going to be only for migrants, but later it seemed better to include photographers from the local area because the idea is for this to be a space for integration between the migrant and the community that receives them and vice versa. The idea was not to use the space to isolate ourselves and focus on the fact that we are migrants. It is a space to integrate interested people, and who are touched in some way, by the phenomenon of migration,” Ferrero told LJR, from Bogotá.

In this mentoring program, which began last April and plans to culminate in August, eight photographers develop a project that revolves around migration with the guidance of a mentor and they attend weekly online classes.

“We allow them to tell the story themselves. Migration is often portrayed by outsiders ... For my part, the idea with this project is to give back a little and give other migrants tools so that they in turn help others in their training. It is a way of expanding the number of voices that narrate the migration,” Ferrero said.

At Semillero Migrante, they seek to decentralize the narrative established in the media, and by journalists themselves, of the migrant walker who suffers and goes hungry. For the creators of the program, migrating is much more than crossing a border and being a migrant is only part of an individual's identity.

An example is the work being developed by one of the program participants: Andrés Pérez, @le_veneque on Instagram. Pérez, a Venezuelan in Colombia, is developing a project on diversity and duality in migration, taking photographs of people considered "queer" or with unconventional bodies. In this way, he tells the stories of individuals without necessarily focusing on their migration process.

Sho Soy de Venezuela

Venezuelan journalist Oswaldo Avendaño emigrated to Argentina in November 2017, where he felt that migration needed to be further humanized and separated from the narrative of figures or misfortune. So, a little over a year later, he created Sho Soy de Venezuela (I’m from Venezuela – with a play on the Buenos Aires accent), an independent journalism initiative that seeks to portray Venezuelan migration in Argentina through photo reports.

The project arose as a personal need for Avendaño to continue doing journalism independently.

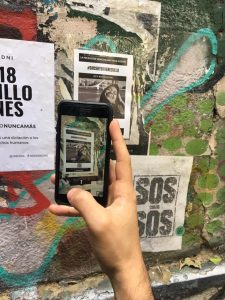

The Sho Soy de Venezuela team put up posters around Buenos Aires to tell the stories of Venezuelan migrants. (Courtesy)

“Not getting a job as a journalist in Argentina, I had to evaluate what my strengths were and what I liked to do. I combined everything, planned and Sho Soy de Venezuela emerged. If I didn't get a job in the media, I understood that I could create a project myself that would keep me doing journalism," Avendaño recalled to LJR.

Sho Soy de Venezuela started in 2019 as a blog to share the stories of Venezuelan migrants in Argentina. However, in 2021 the initiative evolved and they began to post posters in the streets of the city of Buenos Aires with the portraits of the migrants together with a QR scan code to invite passersby to learn more about the stories.

A story that appears on the Sho Soy de Venezuela website is that of José Gregrorio Márquez, a Venezuelan journalist who migrated to Buenos Aires due to the economic situation in his country and the censorship in the media.

“I left Venezuela in 2016 fleeing the crisis. Looking for better job opportunities, a better quality of life, a better future. And, I made the decision when I realized that my salary as a journalist, with 8 years of experience, had been below the minimum salary,” Márquez said in the interview next to his portrait.

Avendaño said the initiative helps to dismantle opinions that disadvantage migrants.

“I am convinced that portrait photos help to empathize. The photos that accompany the micro stories reflect some emotion that migrants have to live with on a daily basis: sadness, joy, nostalgia, fulfillment, etc.,” the journalist said.

Venezuela Migrante

Luz Mely Reyes (Courtesy)

Venezuelan journalist and co-founder of the digital media outlet Efecto Cocuyo, Luz Mely Reyes, is behind Venezuela Migrante, a web portal that seeks to tell the migratory process of those who leave the petroleum-rich country and that also aims to train Venezuelan and foreign journalists so they understand the phenomenon.

Reyes has closely covered and seen the increase in the Venezuelan diaspora, so much so that she defines herself more as a nomad than as a migrant, since she has had to be in constant movement between Venezuela and other countries in recent years.

Venezuela Migrante emerged, according to Reyes, between her stays in Brazil and Colombia where she shared with refugee communities. More recently, she has covered the arrival of Venezuelan migrants to the United States via the Rio Grande in southwestern Texas.

“At Venezuela Migrante, we seek to provide useful content for migrants, specifically those in Peru and Ecuador. But, we also seek to generate networks and relationships among Venezuelan migrant journalists. We want it to be a space where they can meet,” Reyes told LJR.

This idea had begun to take shape in 2018 with Venezuela a la Fuga, a report on the Venezuelan migratory phenomenon that won the Gabo Prize, where the best journalistic stories from Ibero-America are recognized. In 2020, Venezuela Migrante was finally born with the premise of being “a kind of virtual homeland.”

And that's what seems to be forming. Even some of the founders of the other projects that have been mentioned in this text collaborate as writers for Venezuela Migrante.

“I do believe that Venezuelan journalism is reconfiguring itself,” Reyes concluded. “Some have been able to integrate with media in the host countries, others have their own projects, others continue to work for Venezuela from outside, but they are always looking for a way to continue doing journalism.”