Something that began as a small lie between friends ended up in headlines in important Colombian media, and even one international outlet. The “news” drew attention: a young Colombian woman had won a Golden Globe for her role in the acclaimed film by Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki.

“The talent from Barranquilla that won the Golden Globes,” “This is the Colombian illustrator who won the Golden Globe with an animated film” or “The Colombian illustrator who worked on The Boy and the Heron” were some of the headlines that circulated. Within minutes of the news going viral, it was the audiences themselves who began to doubt the story and dispute the information.

Nota con información falsa en la edición impresa del diario El Heraldo (Barranquilla, Colombia)sobre la participación de una joven colombiana en una película ganadora de un Globo de Oro. (Foto: Compartida en redes sociales)

After a few hours of the scandal and noise spreading on social networks, media outlets deleted their articles and in some cases did not give explanations to their audiences. The director of El Heraldo, a Colombian media outlet in Barranquilla, offered a statement in which they apologized to the audience, but received some criticism for mostly blaming the source.

This has not been not the only such case in the country or the world.

In Colombia, there were headlines about the country’s “first astronaut,” who, according to experts, should not be classified as such. There’s also the case of newspaper El País when it published a photograph on the front page in which former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez was allegedly seen intubated in a hospital bed. Or, in lighter “news,” the “joke” made by American late night host Jimmy Kimmel about a wolf that walked through the athletes' locker rooms during the Sochi Winter Games, and which was republished by several media in the U.S.

“What are the consequences of these events? Disinformation. [Media and journalists] are contributing to this infodemic phenomenon, that is, to the amount of 'fake news' or content with political and economic interests that do not correspond to reality," Colombian communicator Mario Mantilla told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “This violates, of course, the rights of audiences, specifically to have truthful and timely information.”

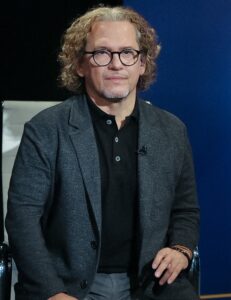

Mantilla was head of the Organización Interamericana de defensoras y defensores de las audiencias (OID), a public editors’ association, from 2019 to 2021.

For experts in journalistic ethics and audience rights, like Mantilla, this scenario in which recognized media end up publishing false information is quite complex.

The problem unites many variables, ranging from new dynamics within newsrooms and the influence of algorithms, to the omission of ethical fundamentals of journalism that shed light on the profession’s responsibilities.

For example, in cases like those mentioned, the omission of something basic is clear: verifying the story and data. This was explained to LJR by Yolanda Ruiz Ceballos, co-head of the Gabo Foundation's Ethics Office.

Periodista colombiana Yolanda Ruiz Ceballos, codirectora del Consultorio Ético de la Fundación Gabo. (Foto: Cortesía)

“We must always think that the source may be lying to us, because doubt is the journalist's core component,” Ruiz said, emphasizing how this doubt leads the journalist to fact-check all the information they receive.

“That work is not being done as it should be done, in general terms,” Ruiz added.

As she explained, it is increasingly common to see that what a single source says is published. Even more serious, in Ruiz's opinion, is to see how this trend is also repeated in “investigative journalism” with a single source. If social media are then used as sources, leading to journalism “with bits of information,” Ruiz said the result is “very dangerous.”

“It seems to me that there is a very great gravity in the way we are relaxing the norms of journalism of confronting sources, of contrasting sources and, above all, of giving context,” Ruiz said.

From his experience as a public editor, Mantilla believes that the media and journalists seem to have forgotten the important role they play in relation to strengthening democracy. In Colombia, he gives as an example, television. In addition to being a fundamental right and a public service, the law remembers that it is not only about entertaining and informing, but about doing so in a truthful and timely manner.

“We must always think that what we do as media contributes to the education of citizens, even if one does not see it as that,” Mantilla said. “Any type of news, any article that one publishes through any of the media, is leaving something in the audience. And that something, as Javier Darío Restrepo said, must be elements that serve as analysis to understand our society and thus be able to make reasoned decisions. In other words, we have a huge responsibility.”

Ruiz highlights another reason for the deterioration in the quality of information circulated by professional media and journalists: the speed with which a newsroom works, especially driven by the search for virality and page positioning. It is not strange then that nowadays journalists must comply with a minimum of daily articles.

“The mere fact that journalists have a production quota is a problem of monumental size. Monumental!” Ruiz emphasized. “Because if they tell you that you have to produce three articles, or five articles or ten articles, obviously that conflicts with the quality of the information.”

But Ruiz is convinced it is a shared responsibility. Journalists and media are firstly responsible for the information that is published. However, advertisers and audiences also have responsibility for what is published.

As she explains, despite the very “impressive” journalistic initiatives that have been born and continue to be born across the planet thanks to the abilities of the digital world, they continue to face the problem of financing. And advertisers, for their part, take the metrics into account when deciding support for initiatives: how many clicks, how many followers, page views, etc.

Tras conocerse la verdad, medios cambiaron sus titulares y artículos, en algunos casos sin dar explicación a sus audiencias sobre la publicación de información falsa. (Captura de pantalla)

“We have fallen into a vicious circle in which what is most emotional circulates more. And the most emotional tends to be the least substantive and that means that the journalism that, ‘sells the most,’ is the most consumed, is the journalism that is not precisely the journalism with the greatest rigor, with the greatest content,” Ruiz said.

“And who does that? Well, audiences. And the fact that journalists respond to what audiences expect and look for,” Ruiz said, pointing out how there are even screens in some newsrooms with social network trends to see what is “moving.”

That is why she is convinced that debate and reflection must also go beyond journalism. She even said that it is urgent to talk about algorithms: what algorithms respond to in order to position certain content or not. Although she is described as “naive” for trying to bring algorithms into the debate, Ruiz said that it is the way to begin to solve the problem.

“It is complex because I believe that in one way or another, audiences, advertisers, media owners, journalists, directors and others make decisions that contribute to the moving machine that is crushing good journalism, keeping it moving,” Ruiz emphasized. “And good journalism is being lost along the way and [people are convinced] ‘that is not my fault, that is the fault of some journalists who are bad, who wake up every day to see how they lie to the world.’”

Literacy of audiences and strengthening of journalistic ethics

Mantilla agrees on involving the audience and is convinced that part of the path to a solution and avoiding falling into the publication of false information even further, involves a serious exercise of audience literacy, as well as strengthening ethics, from universities to workplaces.

With more critical audiences, Mantilla points out, they will be able to demand their rights to receive balanced, truthful information, which is important for making decisions, but they will also be more critical when consuming content.

Comunicador y productor audiovisual colombiano Mario Mantilla, defensor de las audiencias en el canal TRO y expresidente de la Organización Interamericana de defensoras y defensores de las audiencias (OID). (Foto: Cortesía)

Likewise, literacy processes allow audiences to know how decision-making works within newsrooms. In that sense, we could avoid audiences demanding that media publish everything that is seen on social networks as if it were true.

Hand in hand with this education of audiences, Mantilla said he especially believes in mechanisms such as co-regulation and self-regulation. Groups such as journalist associations or media observatories (particularly within universities) are conducive spaces for reflection on journalistic duties and for exercising a kind of control among colleagues.

And finally, Mantilla said self-regulation cannot be left aside. Journalists, directors and media managers must find spaces to reflect and create tools to practice journalism in the best way, he said. Style manuals, codes of ethics, norms within newsrooms that are created by the team members themselves are a good alternative.

“To the extent that self-regulation is something natural in all media, we will have fewer and fewer situations like this and we will also have less legislation that limits, for example, freedom of expression, which would be very serious,” Mantilla said.

Ruiz also invites internal debate from all actors.

“The debate has to be in the profession, obviously. We have to open this debate in newsrooms. Let's discuss if it is necessary to produce 10 articles each. How many are there? How much time do we have? Let's find a way to produce content that is not only based on the excitement and clicks we are looking for. Let's do other things,” Ruiz said. “But also the media owners, what do they want? What is the business format? And advertisers, what is the business format? And the academy. I think it is collective, and that is why it is so complex.”