On April 26, Paraguay celebrates Day of the Journalist in commemoration of the founding day of its first newspaper. After Paraguay achieved independence, El Paraguayo Independiente was established in 1845.

On the same date but in 1991, journalist Santiago Leguizamón was murdered by organized crime in the border city of Pedro Juan Caballero, Amambay department [Paraguay]. The journalist was attacked after leaving the radio station he ran, Mburucuyá 980 AM. He denounced injustices and crimes that were being committed in that city since then.

To date, it is not known whether the crime committed against Leguizamón took place on Journalist's Day as a coincidence or as a clear message from organized crime. Since then, crime has continued to claim the lives of several journalists and threatens many others. Since Leguizamón's death, there have been at least 20 murders of journalists in Paraguay, which have remained in almost total impunity.

Monument in honor of journalist Santiago Leguizamón, murdered in 1991. (Photo: Hugo Diaz Lavigne via Creative Commons)

However, this year's Journalists' Day will mark an important milestone: The presentation in the Paraguayan Congress of a bill for the safety of journalists. Organizations defending freedom of expression have been working on it for months, after several failed attempts to create legislation to provide protection to the journalistic profession.

"Paraguay still does not have a Law for the Protection of Journalists," Dante Leguizamón, executive secretary of the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordinator (Codehupy, by its Spanish acronym) and son of the murdered journalist, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “We have built a project with enough consensus from civil society and from some State institutions. [...] The idea is to present it on April 26, Day of the Paraguayan Journalist and the anniversary of the murder of Santiago Leguizamón.”

The push for this project is part of measures established by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Inter-American Court) in a sentence issued in December 2022. It held the Paraguayan State responsible for human rights violations in the case of Leguizamón's murder.

For Codehupy, the conviction represents a landmark ruling that could be an important step forward in the struggle to make authorities guarantee protection for journalists.

"Regarding the sentence, there are key resolutions," said Leguizamón. "We see that this sentence opens a very important door to negotiate and demand, especially from the State, protection measures for journalists and for the fight against impunity in journalists’ cases."

The Inter-American Court ruling also establishes that the Paraguayan State must adopt measures to strengthen the work of the Roundtable for the Safety of Journalists of Paraguay and jointly create a fund "to finance programs aimed at the prevention, protection and assistance to journalists who are victims of violence."

The Roundtable for the Safety of Journalists is a body made up of state institutions and civil society organizations, such as Codehupy, the Union of Journalists of Paraguay (SPP) and the Society of Communicators of Paraguay, which was formed in 2016 following the exhortation of Unesco to adopt strategies and policies to address violence against journalists.

Although its creation was an important step forward and has served to provide some protection to journalists under threat, the Security Roundtable has its shortcomings and its operation depends on the will of the agencies involved.

"The operation of the Security Roundtable is still very handcrafted. It works based on the pressure we can apply and on the good will of the people who are there. There is no legislation or regulation to compel the proper functioning of that entity," Santiago Ortiz, Deputy Secretary General of the SSP, told LJR.

The Security Roundtable receives reports of threats or attacks against journalists throughout the country and coordinates actions with authorities, such as the Ministry of the Interior or the National Police, to take protective measures. However, these are not necessarily fully complied with, Leguizamón said. In addition, it does not have its own budget that would allow it to implement actions such as the transfer of an at-risk journalist or the purchase of protective equipment.

"Many times the request [of the Security Roundtable to the authorities] is for complete protection, but often only partial protection is offered, such as randomly following [the reporter] or monitoring the area [surrounding the reporter’s home]. And there is a 'back and forth' with the National Police," Leguizamón said. "It is a Roundtable that does not have an independent budget. In other words, it depends on the institutions’ will and actions."

In addition to ordering measures to strengthen the Security Roundtable and to promote the approval of the bill for the protection of journalists and human rights defenders, the Inter-American Court also ordered reparation of damages for the Leguizamón family, as well as the creation of a task force to determine the circumstances of the journalist's murder.

"Just as Santiago's murder was a very hard moment and had a significant impact on freedom of expression, we want the sentence to also have that impact on the protection of journalists, on the fight against impunity," Leguizamón said. "A sentence from an international body is basically a political tool to continue challenging public policies in the fight for human rights. And for the protection, in this case, of a specific group, namely journalists."

The bill that Codehupy and other organizations are working on together with the Human Rights Commission of the Paraguayan Senate envisages, among other measures, setting up a protection mechanism for journalists with the direct participation of State security agencies, Leguizamón said.

This mechanism would have three approaches: Individual protection for journalists under threat; collective protection, including the creation of a support and alarm network for communicators; and social and psychosocial protection to help mitigate the impact of security measures on the life and work of journalists under the mechanism.

"That would also go hand in hand with a budget. We would need for it to be a flexible budget and have enough money to implement measures," the journalist said. "It’s useless to have a well-made or solid institution, if we cannot effectively implement security measures."

Of the 21 murdered journalists in Paraguay since the fall of Alfredo Stroessner's military dictatorship in 1989, eight have taken place in the department of Amambay, most of them in the city of Pedro Juan Caballero. The most recent case was that of Alexander Alvarez, producer of a morning news show at the local radio station Radio Urundey. He was shot dead on Feb. 14 of this year while in his car, waiting for the green light at a traffic stop, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

The other journalists who have been murdered in Amambay are Humberto Coronel, in 2022; Leo Vera, in 2020; Gerardo Servían, in 2015; Fausto Gabriel Alcaraz, in 2014; Carlos Manuel Artaza, in 2013; Samuel Román, in 2004; Marcelino Vázquez, in 2003; and Santiago Leguizamón himself, in 1991.

#ALERTA #PARAGUAY | El periodista, Alex Álvarez locutor de @r_urundey conducía su vehículo esta tarde en la ciudad de Pedro Juan Caballero, cuando fue acribillado por dos sujetos. Llegó sin signos vitales al hospital, pero murió en el quirófano. pic.twitter.com/RGmcc89T27

— Voces del Sur (@VDSorg) February 14, 2023

Amambay is located in northern Paraguay, on the dry border with Brazil. Its capital, Pedro Juan Caballero, borders the Brazilian city of Ponta Porã, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

"It’s the area with the greatest influence of organized crime and the area with the highest homicide levels in the country. We are talking about [that in the area] between Asunción [the Paraguayan capital] and Central [the adjacent department], for every 100,000 inhabitants there are six homicides. In Amambay, that figure could reach 60," Leguizamón said. “There is important evidence that this is an extremely complex area, an area that has a very high level of violence and murders.”

Local and federal authorities have done very little during the last three decades to provide security to the population. Cases of murdered journalists in Amambay enjoy total impunity, to the extent that this and other border departments of Paraguay were designated in 2017 as "silenced zones" for the practice of journalism by the IACHR.

The situation in Amambay has to do with the advance of organized crime, which has co-opted State institutions, including the National Police, the Public Ministry and even the executive branch, Leguizamón said. President Andrés Rodríguez, who led the coup against the Stroessner regime, was linked to drug trafficking cases, and Horacio Carter, who governed Paraguay from 2013 to 2018, was designated in 2022 by the United States for corruption and links to international crime.

"That shows the strength of organized crime in our country, which makes the exercise of freedom of expression quite limited by these levels of impunity for violence and lack of specific protection," Leguizamón said.

Some of the murders of journalists in Pedro Juan Caballero are even predictable, but given the power of organized crime in the region, the protection measures offered by institutions are not enough.

"I could tell you, with much regret, but without fear of being proven wrong, that in the next three years more journalists will be killed in Pedro Juan Caballero," Leguizamón said. "The work that Codehupy and the Union of Journalists have been doing in the Security Roundtable shows that, at this moment, at least two journalists have received death threats in the area. They are under some security measures, which clearly have been historically insufficient."

Some journalists even choose to refuse protection out of distrust of the authorities. Such was the case of Humberto Coronel, who prior to his murder had reported receiving death threats. Coronel, who hosted a news program on Radio Amambay and investigated cases of corruption and organized crime, rejected the police custody assigned to him.

For the Paraguayan Union of Journalists, the violence against journalists in that area has to do with the country's economic and political model, which is characterized by the concentration of wealth in few hands.

"It is a very exclusionary model based on the crooked accumulation of wealth," Ortiz said. "When you denounce that or denounce the privileges of certain sectors, you end up being under threat from these sectors who are very powerful, mainly organized crime. And in some areas this is more evident, as is the case of Pedro Juan Caballero and Amambay."

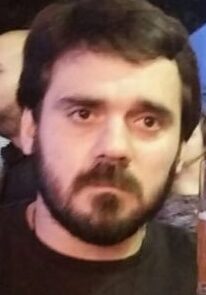

Dante Leguizamón, son of Santiago Leguizamón, is executive secretary of the Human Rights Coordinator of Paraguay (Codehupy). (Photo: Twitter)

In the case of Alexander Álvarez, the police said that the evidence pointed to the fact that the attack that took the journalist's life was aimed at his brother, who was allegedly involved in illicit acts, and ruled out from the beginning that the crime had anything to do with journalism.

"This is the main problem when we talk about impunity. The State does not investigate and says that the murders have to do with other things," Leguizamón said. "That is always the 'answer' that is wielded to distort, even though there are instructions from the State Attorney General's Office that say that the main hypothesis must be work-related. The main hypothesis has to be that, and [the investigations] do not necessarily translate in that sense."

In many of the cases, in addition to negligence and possible complicity, there is a lack of knowledge on the part of judges and prosecutors about crimes against freedom of expression, Ortiz said. Regarding Coronel's murder, the prosecutor in charge blamed the crime on the journalist himself, for refusing to receive police custody. The prosecutor said that Coronel should have "been more careful" after receiving threats and that "a threatened person should take shelter," "try to fix things," and not "give himself away" to crime.

"The Prosecutor's Office has an instruction manual for its officials which prescribes how to act when dealing with a crime against a journalist. It says that, among the lines of investigation, the one that should be exhausted in the first instance is the one linked to his journalistic work," Ortiz said. "The lady [prosecutor in the Coronel case] did not take that into account and made unfortunate and inappropriate statements. That lack of competence is also a real reason for impunity."