Almost five decades after journalist Vladimir Herzog was murdered by Brazil’s military dictatorship, his widow, Clarice Herzog, who is now 83, will receive a state pension as a reparation. A decision by the Federal Court orders a lifelong monthly payment of R$34,577.89 ($5,900 USD) to Clarice. The case underscores the decades-long struggle for justice and memory in Brazil, where impunity for the dictatorship’s crimes persists—even in Herzog’s case, those responsible for his murder remain unpunished.

Herzog’s assassination was one of the most emblematic cases of Brazil’s dictatorship (from 1964 to 1985), and the strong response contributed to the regime’s fall seven years later. The case has been the subject of multiple rulings, including a landmark 1978 decision in which Brazil’s judiciary condemned the federal government for his illegal detention, torture, and death. In 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in Costa Rica reaffirmed the decision, condemning Brazil for failing to investigate and prosecute those responsible.

In 1996, a Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances officially recognized that Herzog was murdered, but his family refused the compensation offered, arguing the state should continue investigating the crime. The reason for accepting the pension now is that Clarice Herzog, who lives with Alzheimer’s disease, needs help paying for medical care, Ivo Herzog said.

“My mother never wanted to pursue financial compensation because she feared it would make it too easy for the state to resolve the issue—just write a check, and that’s it,” Ivo Herzog, Clarice and Vladimir’s son, told LatAM Journalism Review (LJR). “For her, the fundamental issue has always been proving he was murdered and seeking accountability for those responsible.”

Vladimir Herzog, known as Vlado, was a journalist, professor, and filmmaker. Born in Croatia—then part of Yugoslavia—in 1937, his family settled in Brazil in 1942. He began his journalism career in 1959 at the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo. In the early 1960s, he married Clarice Herzog, with whom he had two sons, Ivo and André. Over the 1960s and 1970s, he worked for several outlets, including the BBC’s Brazilian Service in London and Visão magazine. He also taught journalism.

In 1975, he was appointed news director at TV Cultura, a public broadcaster owned by the São Paulo state government. He became the target of a smear campaign led by members of the pro-dictatorship political party ARENA in the São Paulo Legislative Assembly. That year, on October 24, Army agents summoned him to testify about alleged ties to the Brazilian Communist Party, known for its initials PCB, which was banned under the regime.

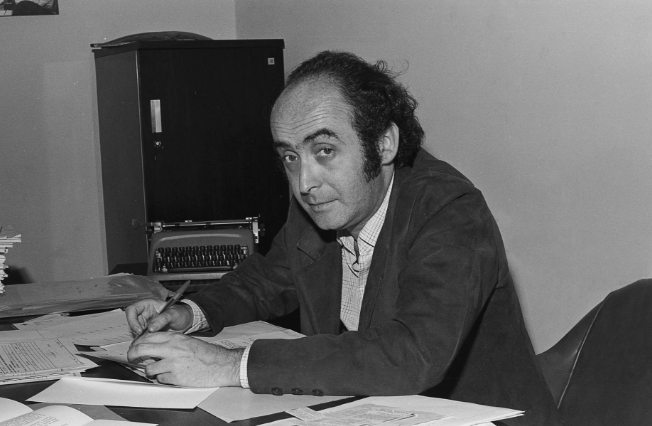

Journalist Vladimir Herzog at his desk at TV Cultura on October 9, 1975, weeks before he was murdered by Brazil’s military dictatorship (Photo: CEDOC TV Cultura / Acervo Vladimir Herzog)

The next day, according to the Vladimir Herzog Institute, he voluntarily went to the headquarters of the Army’s DOI-CODI intelligence unit, where he was detained along with two other journalists, George Duque Estrada and Rodolfo Konder. During questioning, Herzog denied any links to the PCB. Afterward, the other two journalists were taken to a corridor, where they heard an order to bring the electric shock machine. Loud music was played to drown out the sounds of torture, and Herzog was never seen alive again.

Hours after his murder, the Army claimed Herzog had hanged himself with a belt, even releasing a staged photo of his body inside a cell. In 2012, the photographer, Silvaldo Leung Vieira, admitted to Folha de S.Paulo that the image was staged—one of the many lies told by the military during the dictatorship.

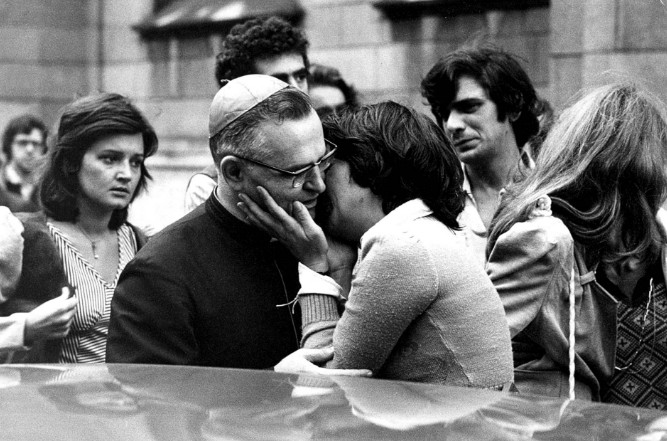

The outcry over Herzog's death was immense. The dictatorship's lie was made public and its brutality laid bare, sparking a wave of public protests. A week after his murder, more than 8,000 people attended an interfaith service at São Paulo’s Sé Cathedral.

Among those present was Márcio José de Moraes, at the time an apolitical lawyer who would later play a central role in the case.

“I was indifferent to these issues,” Moraes told LJR. But “when I saw the headline that he had died, I was completely disillusioned. I thought to myself, ‘I’ve been a useful fool. That was my political awakening.”

Clarice Herzog and Cardinal Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns leave the ecumenical service held at São Paulo’s Sé Cathedral on October 31, 1975, in memory of journalist Vladimir Herzog, who was murdered days earlier by Brazil’s military dictatorship (Photo: Acervo Vladimir Herzog / Estadão Conteúdo)

Months after the murder, Clarice Herzog and her two sons filed a lawsuit in São Paulo’s courts—during the military regime—seeking an official declaration of the state’s responsibility for Herzog’s illegal detention, torture, and death.

Clarice refused to seek financial compensation, fearing it would blur her objectives. “She told us: ‘My lawsuit is political. I have a political objective,’” family lawyer Samuel Mac Dowell Figueiredo told LJR. “She wanted a case that directly confronted the regime. And that’s what we did.”

The case unexpectedly ended up in the hands of former lawyer Márcio José de Moraes, who had become a judge. The judge originally handling the casewas about to retire and had already prepared his ruling. He scheduled a hearing to announce the decision, but the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office obtained an injunction preventing him from disclosing it. The next day, Moraes, who was the substitute judge, took over the case and wrote a new ruling.

In 1978, at the age of 29, Moraes had been a judge for just over two years. He recalled that the Brazilian judiciary operated under a climate of oppression, with senior judges—appointed rather than selected through competitive exams—hesitant to criticize the military government. However, he also noted an evolution in public law within the Federal Judiciary. Some Brazilian legal scholars had recognized that the 1967 Constitution, drafted under the dictatorship, contained provisions that allowed for rulings contrary to the regime’s interests.

“The Herzog case marked a shift in our legal interpretation against the dictatorship,” Moraes explained. “I expanded its interpretation to hold the federal government accountable for Vladimir Herzog’s torture and death.”

On October 27, 1978—three years after the crime—Judge Moraes issued a landmark ruling. He declared that Vladimir Herzog had not died of natural causes while in government custody. The ruling also deemed Herzog’s detention illegal, concluding it involved abuse of authority and clear evidence of torture. Never before had Brazil’s judiciary published such a strong decision against the dictatorship.

“What mattered most at that moment was establishing the state’s responsibility for persecution, murder, and torture,” said attorney Mac Dowell Figueiredo. “Holding individual military officers accountable was important, but it wasn’t the primary issue. The priority was institutional—we were fighting a military dictatorship, and civil society was united in that goal.”

In addition to holding the state accountable, Judge Moraes requested the case be sent to the Military Justice Prosecutor’s Office for an investigation and prosecution of those individually responsible for the crime. Clarice Herzog filed several other legal requests for further investigations, but they were never heard.

One major obstacle to justice was the Amnesty Law, enacted by the military regime in 1979, which granted pardons for political crimes committed between 1961 and 1979. The prevailing interpretation of the law extends its protection to torturers and other agents of the dictatorship.“It’s a distorted interpretation,” Ivo Herzog said. “But the fact is, the ordinary courts at all levels have dismissed the case, either citing the Amnesty Law or, later, arguing that the statute of limitations had expired.”

In 2009, Clarice Herzog filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights requesting an investigation into the Herzog case. Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the Brazilian state was responsible for failing to investigate, prosecute, and punish those responsible for Herzog’s torture and murder. The ruling also held Brazil accountable for violating the rights of Herzog’s family to truth and personal integrity.

Initially, Ivo Herzog was against taking the case to the Inter-American Court, exhausted from 40 years of fighting for justice. However, his mother convinced him to move forward, arguing that his father’s case was emblematic and could pave the way for other families seeking justice. The legal process was long and arduous, with difficult moments in court, including offensive statements from military officials directed at his mother, said Ivo Herzong. Ultimately, the case was victorious.

“The ruling went far beyond what we expected because it didn’t just address my father’s case—it applied to all those who faced similar situations,” Ivo Herzog said. “The decision says the Brazilian government has an obligation to investigate these crimes, which are crimes against humanity—unforgivable offenses to which no form of amnesty applies. It was the first time in Brazil’s 500-year history that the country was condemned for crimes against humanity.”

And yet an individual investigation into these crimes has never materialized. In 2013, Vladimir Herzog’s death certificate was amended to reflect that he died due to physical violence rather than suicide. Last year, Brazil’s Amnesty Commission officially recognized the harm suffered by Clarice Herzog during the dictatorship. The family could have sought financial compensation years ago but only did so recently due to financial difficulties arising from her health condition.

Since 2009, the family has operated the Vladimir Herzog Institute, an organization dedicated to preserving the memory of Herzog’s case, exposing other crimes committed during the dictatorship, and advocating for freedom of expression, democracy, and human rights.

The latest legal decision in favor of Clarice Herzog comes at a time when Brazil is once again grappling with authoritarianism. On one hand, the film I’m Still Here, which tells the story of former congressman Marcelo Rubens Paiva’s murder by the military regime, is competing for an Oscar in three categories, including best film. On the other, far-right groups are calling for amnesty for those convicted of storming Brazil’s government buildings on January 8, 2023, in an attempted coup, as well as for former president Jair Bolsonaro, who is set to stand trial before the Supreme Court this year for his role in the coup attempt.

The renewed push for amnesty outrages Ivo Herzog.

“Amnesty is for political crimes—when someone is persecuted by the state for their beliefs and faces imprisonment or exile,” Ivo Herzog said. “But now, people go out, destroy property, set fires, throw bombs—and they want amnesty? What they really want is to allow a fascist, authoritarian ex-president—who has always defended the dictatorship and its murderous torturers, who says the problem with Brazil’s dictatorship was that it didn’t kill enough people—to escape justice and return to politics.”