Two new laws and the suspension of funding through US agencies could deliver the final blow to independent journalism in Venezuela. The new pieces of legislation are part of a long history of restrictive and criminalizing measures imposed by the regime of President Nicolás Maduro to silence critical voices, according to journalists and experts in that country.

Although these laws are not specifically directed at the press, their collateral impact would restrict the exercise of journalism and freedom of expression, according to organizations defending press freedom, which have expressed concern about the potential violation of fundamental rights and the obstruction of the flow of information.

The above, added to the recent executive order by President Donald Trump to suspend financial aid from the U.S. to foreign organizations, and the Maduro government's discourse criminalizing media that received this type of financing, leaves the independent press with very few options to carry out their work.

Two laws that would affect the free operation of independent media in Venezuela came into effect in the last months of 2024. (Photo: Screenshots of the Venezuelan Official Gazette)

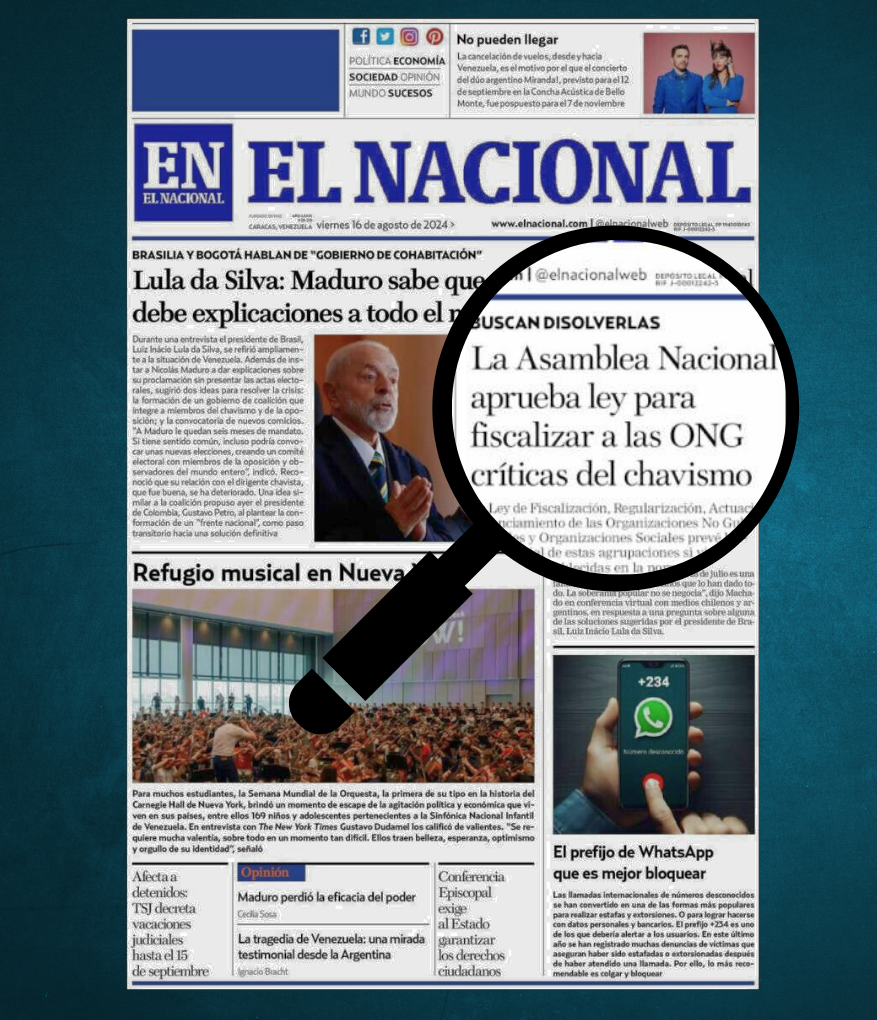

One of the new laws in question is the Law on Control, Regularization, Operations and Financing of Non-Governmental Organizations and Non-Profit Social Organizations. Popularly known as the Anti-NGO Law or Anti-Society Law, it was approved on Aug. 15, 2024 and came into force three months later.

The objective of the law is to regulate and supervise the activities of NGOs that operate in Venezuela. In the country, a large part of the independent media are established as nonprofit organizations, according to the Press and Society Institute of Venezuela (IPYS, for its initials in Spanish).

The law requires NGOs to register with authorities with statutes aligned with the new regulations. As part of this process, they must provide detailed information about their finances, including the national or foreign origin of their funding sources, the record of donations received, and even the identity of their donors.

The requirement that the media hand over their financial information to comply with the new law raises alarm bells, said Saúl Blanco, program officer for promotion, defense and public action at Espacio Público, a Venezuelan freedom of expression defense organization. Furthermore, he said, the Anti-NGO Law was approved in a context of increased persecution of journalists and human rights defenders after the post-electoral crisis in Venezuela.

“For the State to have information about the financing of organizations can mean a new wave of repression against civil society organizations, especially taking into account that there is a criminalization of external financing by State officials,” Blanco told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Failure to comply with the obligations provided for in the new law will be punished with penalties ranging from fines to cancellation of the organization's registration. However, the law also establishes that failure to comply with obligations could give rise to civil and criminal sanctions established in other laws.

Melanio Escobar, a Venezuelan journalist and activist specializing in freedom of expression and human rights, warned that financial information from NGOs could be used as evidence to create cases under laws with gray areas of interpretation, such as the law against terrorist financing or the law against hate. Although the Anti-NGO Law does not include prison sentences, those other laws do.

“Without having any type of evidence in its hands, the regime has already used international financing to criminalize, discredit and attack media outlets, journalists and organizations,” Escobar told LJR. “You can imagine what can happen if the organization voluntarily delivers to the Venezuelan State information and amounts of what the projects are, their purpose, who the donor is, and in what timeframe they must be executed.”

Experts question the real need for the new law, beyond serving as an instrument of control and repression. Many of the new requirements do not make sense within the Venezuelan legal system because there were already regulations that regulate NGOs, Blanco said.

In addition, much of the information that authorities are requesting from organizations is already public and easily accessible, especially those that are registered abroad, added Escobar, whose organization and news outlet RedesAyuda operates from the U.S.

“When you have an organization registered in the United States, you tell the [American] State how much you receive, who you receive it from, how it was spent, etc. And those tax returns are public,” Escobar said. “If the Venezuelan State wanted to know who finances it, how much they finance, or under what project they finance an organization, it can do so with a Google search.”

Another aspect of the Anti-NGO Law that worries experts is the prohibition of registration, and therefore the possible closure of the organization, for NGOs that "promote fascism, intolerance or hatred," and those that carry out activities "for political purposes," as the law states. That represents a wide risk because it leaves the definition of these concepts open to the interpretation of authorities, Blanco said.

“The issue is that ‘political’ is a very broad term. Working for human rights already falls within the political sphere,” Blanco said. “If the Venezuelan State determines that media outlet X was ‘inciting hatred’ against an official, the organization could be subject to annulment and with this, well, basically the media outlet could no longer exist.”

Another law that was approved last year, the Organic Law Liberator Simón Bolívar against the Imperialist Blockade and in Defense of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, commonly known as the Simón Bolívar Law, also includes regulations that could represent legal obstacles for the press.

Venezuelan journalist and activist Melanio Escobar said that the Maduro regime seeks to set aside social oversight with the approval of laws that criminalize journalistic work. (Photo: Screenshot from Melanio Escobar's YouTube channel)

This law was announced as a measure to defend the country against blockades and sanctions imposed by foreign countries on the Maduro government. However, IPYS said that it is actually part of the regime's strategy to criminalize information and opinion, and to make censorship official when it comes to matters of public interest.

According to said law, media, journalists or any person who disseminates content that is considered to promote international sanctions against officials or state companies will be subject to the revocation of their concessions and fines of up to 50 million bolivars [more than US$776,000].

“Even without a prior procedure and on the basis of suspicion, the law allows restrictive economic measures to be imposed,” IPYS said in an analysis of the legislation.

In addition, the Simón Bolívar Law establishes the creation of a national registry of people suspected of being involved in “actions contrary to the values and inalienable rights of the State,” which could be sanctioned with restrictive economic measures, including the freezing of assets and the prohibition of establishing commercial or civil companies.

“Due to the recurrence of stigmatizing discourse against the independent press, which total 95 events in 2024 according to IPYS Venezuela records, any media outlet or journalist runs the risk of being incorporated into said registry and being under latent threat,” IPYS said in its analysis.

For Escobar, the intention of the Maduro regime in putting NGOs and media on the ropes through legislation like these is to consolidate a communication hegemony that they have tried to impose for several years in order to control the narrative about what’s really happening in the country.

“They don't care about what happens in Venezuela, what matters to them is how what happens in Venezuela is told and they want to dominate that narrative and the only way to dominate it 100 percent is to close all the media and human rights organizations,” Escobar said. “This is a way for them to get the social control off their backs and be able to continue with their dictatorial and criminal actions.”

According to Escobar, since the government of the late President Hugo Chávez withdrew the concession to the channel Radio Caracas Televisión (RCTV) in 2007, for alleged violations of telecommunications laws, Chavismo understood media critical of power could be criminalized through the creation of laws.

“According to their narrative, they are not putting anyone in prison for expressing themselves, but that person broke the law against hate and they are only imposing the law,” Escobar said. “Or they are not going to close an NGO that was asked to be audited, but rather, since [the organization] did not want to do so, it can no longer operate.”

Although the new laws could affect the operation of independent media in Venezuela, what most seriously threatens the survival of journalism in the country is the suspension of aid from US entities, according to Venezuelan journalists and experts.

“In the situation in Venezuela, companies either do not want to finance journalism, or they do not have money. And if they have it, they are under threats from the government to not do so,” a Venezuelan journalist who requested anonymity told LJR. “So, how can we sustain journalism if not with international help?”

The journalist said that, despite the persecution and judicial harassment that the critical press has suffered in recent years, their outlet has been able to circumvent the threats by trying to gauge the regime's reaction after the publication of its investigations and adjusting its publication strategies accordingly.

“Despite the existence of these draconian laws that place us in a situation of legal vulnerability [...], what is really achieving the goal of suffocating civil society and the media is what unfortunately the Donald Trump government is doing through [the cancellation of support from] USAID and other organizations,” the journalist said.

In Venezuela, media and NGOs affected by the suspension of US funding have remained silent in light of the narrative promoted by the regime, which maintains that resources from US agencies have been used to destabilize the country and attempt to overthrow Maduro.

News media that operate as NGOs have few options to avoid being affected by the application of the new legislation.

The purpose of the Anti-NGO Law is to regulate the activities of non-profit organizations operating in Venezuela, including dozens of independent media outlets established under this legal structure. (Photo: Screenshot and Canva)

In the case of the Anti-NGO Law, in legal matters, organizations could present requests for protection, or even request the annulment of the law, Blanco said. However, he added that considering the lack of independence and impartiality of the Venezuelan Judiciary, it is unlikely that such measures will work.

“This law effectively affects the right of association, the right to privacy and other rights,” Blanco said. “But the issue is that even when one can argue this, and even when this makes sense, many times the Venezuelan State has made decisions contrary to human rights to protect certain public interests.”

Escobar said that, in the absence of legal protection, media outlets that operate as NGOs have two options: face oversight with the hope that the information provided will not be used against them, or simply fail to comply with the law.

“I think that all newsrooms and all human rights organizations are discussing whether we are going to enter into illegality or if we are going to comply with the legal requirements that the Nicolás Maduro regime is giving,” Escobar said. “So far I have not met anyone that has decided to be audited, within the ecosystem where I work. Among the organizations I have spoken with, they are deciding.”

The journalist, who asked to remain anonymous, said the registry only affects media outlets that operate as civil associations and not as public limited companies. In addition, the law cannot sanction media outlets that operate from exile.

However, closing operations in the country to transfer to a foreign country multiplies the difficulty of doing journalism about Venezuela, Escobar said. Not only is it more expensive to hire staff in other countries, but the risks are also increased when carrying out coverage within Venezuela.

“I can no longer hire a journalist in Venezuela to cover the news for me or to produce the story for me if I am no longer operating there. That even represents a risk for the journalist, working for me illegally,” he said.

The Anti-NGO Law establishes a period of 90 days after its enactment for organizations to present their statutes adjusted to the new regulations. This deadline was Feb. 13. NGOs whose statutes do not comply with the provisions of the new law have until May 14 to reform them.