After two installments (first and second), we are back with the third volume of the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) Glossary of journalistic expressions in Portuguese, English and Spanish.

The subject is refrito, I admit, but it is an original suite, not least because the first two lists served as a perfect borrego and I longed for a rowback.

Before the list, I need to leakum bastidor of our work at LJR: my editor Teresa Mioli hates it when I use the word bastidor in my writings. But, since she knows I'm not a cascateiro, it's hard to kill my stories.

This new list was compiled in part from suggestions that arrived via email latamjournalismreview@austin.utexas.edu and Twitter to LatAm Journalism Review.

Bastidor is what happens away from the public eye | Photo: Marcos Corrêa/PR

In Brazilian newsrooms, bastidor (“backstage”) is a term widely used to refer to information that circulates outside the reach of the public and, therefore, is of journalistic interest. The term is borrowed from the theater, where we have the stage, where the spectacle is visible to the public, and the backstage, where the preparation and all its mishaps take place. That's why in English the word is often literally translated to “behind the scenes.”

“The bastidores of politics and economics, in particular, deserves permanent journalistic investigation,” teaches Folha de S.Paulo's Writing Manual.

Similarly, in Spanish, transcendió is used to refer to information the journalist knows is true, but cannot be attributed, and often circulates behind the scenes of public and private power, and therefore is of great relevance and priority for journalists looking for scoops (see glossary) about political and business deals.

In English, information that transcendio (happens) bastidores (behind the scenes) is usually obtained through off-the-record conversations with sources who are unwilling or unable to identify themselves.

Edward Snowden: Leaks of classified US government documents. Credit: Laura Poitras / Praxis Films

Leaks are all about the behind the scenes. They happen when the journalist has access to information that is not yet public, or that a priori would not be public. In the ideal world, leaks are a way for sources to reach the public with information that would otherwise be kept secret and remain anonymous, protected by source secrecy.

That's how the general public learned what was going on behind the scenes of the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, and more recently, they learned about the existence of the U.S. National Security Agency's (NSA) global surveillance program and a series of U.S. military operations during the War on Terror.

Other recent cases of global impact were revealed by the International Consortium for Investigative Journalism in the cases of the Panamá Papers, Swiss Leaks and FinCEN Files.

Leaks, however, as journalism manuals like the AP teach, must be dealt “with skepticism and extreme caution. (...) And the authenticity and accuracy of any hacked or leaked data sets should be confirmed before their use.”

Trial balloon: a trap for the journalist that can result in scoop or mistake

If a journalist is not careful, he could fall for a source's balão de ensaio, or trial balloon. It occurs when a source, usually from the government, leaks information from behind the scenes in order to assess the impact on the public of a policy under internal discussion. As the source asks to be off the record for the leak, he protects himself from any negative repercussions and can rethink the measure that has not yet been officially launched.

Balão de ensaio is a term borrowed from aviation and refers to a small balloon used to test weather conditions.

The Oxford English Dictionary notes trial balloon being used in 1968 to talk about Teddy Roosevelt: “He also originated the ‘trial-balloon’ technique and gave favored correspondents ‘off-the-record’ statements that they attributed to ‘authoritative sources’. If the statement caught on, Roosevelt would make it his own. If it fell flat, he would drop it.”

In Spanish, however, at least among Mexican journalists, everyone will understand that soltar un borrego (literally, “releasing a sheep”) is the same as spreading false news deliberately with bad intentions.

“It is likely that it refers to the fact that if the story ‘hits’ it can be followed by other media outlets, like sheep, thereby contributing to achieving what the person who released it wanted,” wrote journalist Mario Maraboto.

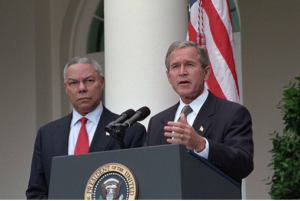

Colin Powell and George W. Bush: Weapons of Mass Destruction story was a mix of leaks and trial balloons that resulted in a huge cascata. Source: The U.S. National Archives

Cascata is a word that in Portuguese means a waterfall and also a lie. Therefore, a cascata in journalism is nothing more than “information without a basis in real facts.” While in the trial balloon the journalist is the victim of a source, in the cascata he is the one to blame for the falsehood of the published information. It can also refer to long, inconsistent text. Whoever writes a cascata is a cascateiro.

In Spanish, and again in Mexico, information that is published but is not true is defined as volada. It comes from the verb volar (“to fly”).

“A ‘volada' is information that is taken for granted without having been investigated. It is a story invented by a journalist that, if well done, can be credible and reach unanticipated levels,” Maraboto wrote.

In U.S. journalism, a classic volada the result of a mixture of a leak and a trial balloon, was the accusation that the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. The cascata stirred up public opinion and supported the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the overthrow and eventual execution of Hussein, without any such weapon having been found. Years later, the government admitted an intelligence failure.

In a media outlet that values the best journalistic values, trial balloons, cascatas, voladas and borregos demand immediate repair, with the admission of error and correction. In some cases, they can even result in internal investigations and dismissals. In others, the media outlet’s liability is minimized by the outlet itself.

Americans call this a rowback. That's when correction isn't quite a correction when admission of error comes with unnecessary justification.

Or, according to the book “Melvin Mencher’s News Reporting and Writing,” a rowback is “a story that attempts to correct a previous story without indicating that the prior story had been in error or without taking responsibility for the error.”

We couldn't find a similar expression in Portuguese or Spanish, which doesn't mean we've never seen rowbacks in Latin America.

Content that is requentado or refrito is not fresh

Like meals from the day before, content that is requentado (literally, “reheated” from Portuguese) or refrito (literally “refried,” from Spanish) do not have the freshness expected from journalism. They usually do not contain original information or field reports, and are produced from the newsroom to add volume to the news quickly and cheaply.

In English, aggregation is used to indicate a story based on other news sources, press releases or news agency content. English journalist Nick Davies pejoratively refers to this practice as churnalism in his book “Flat-Earth News.”

Good journalism dictates that a report that is inconsistent, inaccurate or with gaps in information is derrubada (literally, “thrown out”) either by the reporter or its editor. Anyone who knows the bastidores of a newsroom knows that this is the case in many attempts at trial balloons or borregos, or even with content that is requentado or refrito.

In English and Spanish, journalists treat poor quality reports even more seriously: they say kill the story or matar la nota. Maybe it’s better, so as not to run the risk of it rising and taking to the production line again.

Instead of requentar or refritar, the ideal is to suitar, as they say in Brazilian newsrooms, or follow up in English, or hacer una historia de seguimiento, in Spanish.

In the three languages, the meaning is the same, that is, to follow up on a subject, to produce new reports in the coverage of a case. But in Portuguese it comes from French, suit, that is, to continue, to follow.

A good suíte can be even better than the original story, and follow-up coverage can result in impactful journalism. Otherwise, it may result in a report that is requentada.

Journalists from Latin America who sent in suggestions after we published the first and second editions of the glossary of journalistic expressions collaborated in the development of this list. if you have any suggestions, send them our way in any language to latamjournalismreview@austin.utexas.edu, or send us a message on Twitter.