An interesting movement is beginning to emerge, albeit belatedly, in Latin America: the creation of innovation laboratories, or media labs, in news outlets of the region. Inspired by a global trend, the labs are spaces, real or virtual, of interdisciplinary innovation, in which the aim is to develop innovative thinking, accelerate the application of technology, seek solutions to problems and make journalistic impact.

The article "Innovation in journalism: how media labs are shaping the future of media and journalism," published in the academic journal Brazilian Journalism Research, identifies an increase in the number of labs in media organizations since 2014.

"We're talking about less than ten years in which we started to really see media companies creating innovation labs," one of the paper's authors, researcher Ana Cecília Bisso Nunes of PUCRS, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "

"When we look at this context of Latin America, it seems that the phase of these labs moving to being created by companies and having more labs from companies and more independent media and journalism labs, seems to be up-and-coming."

According to researcher Ana Cecilia Bisso Nunes, media labs are more prevalent in digital natives than in legacy media organizations. Photo: courtesy

According to Bisso Nunes, in Latin America, media labs associated with universities is still the most common modality, unlike what happens, for example, in the United States and Europe. One of the reasons for this, according to the researcher, are the costs associated with anything that is not directly related to the core business of journalism, especially in more traditional companies. This is why, in Latin America, examples of innovation labs are more prevalent in digital natives.

"The financial issue is important. For those legacy, traditional companies, this is still a barrier, a bigger risk. For digital native companies, building this kind of lab is going to be a much smoother process of establishing this kind of structure because the barriers to innovation culture are lower," Bisso Nunes said.

For this article, LJR talked to journalists responsible for media labs in three media outlets in the region: la diaria (Uruguay), Pública (Brazil) and OjoPúblico (Peru). Following different approaches, the three share a similar focus: the use of technology to bring the newsroom closer to the audience. In the case of la diaria, this is fundamental to guarantee the financial sustainability of the business. For OjoPúblico, it’s a way of finding collaborators in other news outlets and regions of the country. At Pública, the experience with the lab yielded an important lesson: technology serves to solve problems, and not to make them bigger by creating access barriers.

In the genesis of the Uruguayan newspaper la diaria, a print publication launched in 2006, the challenge was how to dispense with newsstand sales for the distribution of the paper edition. With no advertisers, the then-new newspaper, owned by a cooperative of workers, had in readers its main source of income, but the share that fell to the newspaper owners would make the business unfeasible. This need led to innovation, in a model that took a chance on 100% of income on subscriptions, which guarantees the newspaper's financial health to this day.

"We wanted to build a news outlet that was distinct, but in competition with legacy newspapers, and we realized that we would have to do it outside of the existing distribution system in the country, which was the newsstands. (...) We didn't accept the conditions that the distribution system imposed on us," Damian Osta, innovation manager at la diaria, told LJR. "La diaria has in its DNA an innovative vein. (...) Innovation in the developed world is obviously a child born of abundance. In our case, we innovated many times because we had to survive. And that's where we had to reinvent ourselves and reach the limits of the possible."

La diaria lab works on the second floor of the Uruguayan newspaper's newsroom. (Credit: Courtesy)

Since 2016, the newspaper has maintained the la diaria lab on the first floor of the three-story building where the newsroom operates, in the old downtown of the capital, Montevideo. This is where journalists and other professionals work to develop products, processes and strategies that will become part of the newspaper’s routine and its readers.

The first major project managed by la diaria lab was Río Abierto, in which the newspaper's subscribers sought out scientists researching water resources and water use. From there, a model of specialized journalism was designed that articulates the knowledge available in the reader base, in which subscribers advise the journalists' work. Today, the "specialized journalism units" of la diaria include education, science, environment, economics, labor, and health.

More recently, it was also from the community of readers that la diaria lab launched a system to monitor the projection of electoral results. And, currently, the lab team is working on investigating applications for blockchain technology in the journalistic process.

"We in the media are innovation takers. We belatedly adapt everything that the big platforms create. And we do it uncritically. We are all the time running after the latest thing we have to do. But our experience shows that it's not that way. We try to rely as little as possible on the technology provided by the platforms to reach our audience," Osta said.

The Journalistic Innovation Lab of Agência Pública de Jornalismo Investigativo in Brazil operated on a limited basis between 2016 and 2019. By promoting collaboration among professionals from different fields to produce feature stories, the lab experimented with a series of tech apps in journalism. In all, six major reporting projects were developed that paired new technologies to tell stories.

"One of the main [lessons], and that's why we only did these six of them and then stopped, is that we ended up discovering along the way that there is often a fetishization of the use of technology. Journalists often use tech for themselves, out of their desire to innovate. It’s innovation for innovation's sake. And it’s not so easy for the public to access that kind of thing. The public prefers something simpler, with a user experience as simplified as possible," Natalia Viana, Pública's executive director, told LJR.

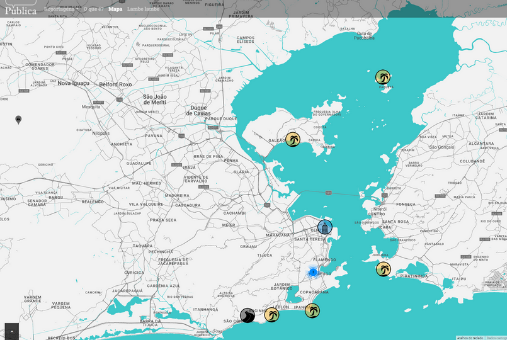

Among the tech tools tried out by the Pública Lab are databases, interactive games, collaborative maps, applications, bots, and 360 video. Three of these specials were recognized in national and international journalism awards.

Developed within the Pública lab, the special feature story on the privatization of public spaces had readers denouncing the closing of beaches. (Credit: Screenshot)

Viana listed three innovations from the lab that, according to her, "worked very well." All of them have in common the possibility of audience participation, either collaborating in the research or using the available data for further research.

"[With] the interactive beach map, people really mobilized on the issue of beaches in Brazil. This was a learning experience, it surprised us, but we received hundreds and hundreds of complaints of beach privatizations. One thing Brazilians like is the beach. So, on this one, what worked was the public’s interest to use participative journalism," Viana said.

One of the “offspring” of the Pública lab that is still active is Robotox, a Twitter bot that tweets every time the Brazilian government authorizes a new pesticide on the market, developed in partnership with Repórter Brasil.

"It is a code that scans the Official Federal Gazette (Diário Oficial da União or DOU, by its Portuguese acronym), transforms it into text and tweets it. It is used a lot as a reference. It is simple and responds to a real demand. Some of our journey was like this. The use of technology works when it responds to a need," Viana said.

OjoLab: open source mentality applied to journalism

Behind OjoLab, the journalistic innovation lab of the Peruvian investigative website OjoPúblico, is the open-source mentality present in the tech community. Since the site's launch, OjoPúblico journalists have approached tech experts in order to develop innovative tools and methodologies in journalism. Among them is the anti-corruption algorithm Funes, which identifies evidence of corruption based on cross-referencing of public data.

"We knew practically nothing about technology, and our entry into this world came about thanks to us coming together with the tech in Peru," David Hidalgo Vega, news director at OjoPúblico, told LJR. "When we got in touch, we learned that the tech community is very open and we absorbed that mentality."

As a result, OjoLab has been operating for five years as a training center for journalists and the general public to spread investigative techniques that strengthen journalism. If on one hand OjoLab offers OjoPúblico's audience more transparency about the journalistic process, contributing to its credibility, it also trains journalists from the interior who may eventually work in collaborative investigations.

"There's a big difference between the new methodologies and ways of working in independent online journalism, basically, versus what has been the traditional media industry, which is quite closed and unidirectional. Instead, these new experiments aim to promote a more horizontal relationship with readers, with other actors in society. And I think that's very valuable right now," Vega said. "When we have an innovation component, we try to spread this example through OjoLab."