As the day dawned on Feb. 6 of this year, shortly before 6 a.m., insistent knocking on the door of his house woke journalist Alexandre Aprá in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Civil Police agents executed a judicial search and seizure warrant from the Police Inquiries Center (NIPO, for its acronym in Portuguese) signed by Judge João Bosco Soares da Silva after the state governor, Mauro Mendes from the União Brasil party, filed a complaint with a police station specializing in digital crimes.

“The police collected electronic devices, computers, iPads. They did not make any other type of seizure,” Aprá told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “It was an operation to try to discover my sources. I never imagined they would take this absurd escalation, but this is a picture of this scenario of complete misuse of the branches of government. Atrocities are happening in Mato Grosso.”

Mauro Mendes, the governor of the state of Mato Grosso, in Central-West Brazil (Foto: Geraldo Magela/Agência Senado)

Two other journalists, Enock Cavalcanti and Marco Polo de Freitas Pinheiro, known as Popó Pinheiro, were also targeted by operations at their homes that morning. The three were accused of the crimes of major slander (calúnia majorada), major harassment and criminal association for republishing on Sept. 23, 2023, excerpts of a report, from website Repórter Brasil. Written by Daniel Camargos and Daniel Haidar, that report alleged that, despite being a partner in a mining company, Appellate Judge Orlando de Almeida Perri, from the Mato Grosso Court of Justice, acted in a judgment related to the mining sector in the state.

The Civil Police made a request to the Court for preventive detention warrants against Aprá. For all three journalists, they requested warrants for the removal of content, for a home search and seizure and for the breach of confidentiality of the electronic devices seized from the three journalists. The request for detention was denied by the Court, but the other requests were granted.

These cases, which were criticized by Brazil's main freedom of expression organizations, are emblematic of what journalists who publish unfavorable news about Mendes face. There is information about 18 journalists being sued, prosecuted or investigated after writing about the governor and his allies.

The targets of the cases say that the governor has the support of Mato Grosso's judicial institutions.

“We have no hope whatsoever in local bodies, because there is brutal misuse of institutions,” Aprá said. “There is a great deal of promiscuity between the powers, and Mauro Mendes is moving worlds to silence us.”

Meanwhile, the governor says he is a victim of slander (calúnia) and defamation, and that he has the right to seek justice. The Civil Police stated that the process is confidential and that it has collected elements that show a coordinated action for the "fabrication and dissemination of fake news and digital files." The public prosecutor’s office of Mato Grosso, which approved the police actions, said the confidentiality of the investigation is in place so its progress is not impeded, and that the actions do not harm freedom of expression or the right to source confidentiality.

On Wednesday, March 6, the Supreme Federal Court (STF, for its acronym in Portuguese) granted a preliminary injunction related to the search and seizure of the electronic equipment of the journalists, and suspended the decision of the Judiciary of Mato Grosso. In her decision, rapporteur Carmen Lúcia cites the unconstitutionality of prior censorship, the impossibility of journalists working after having their materials seized and the violation of source confidentiality as reasons.

Aprá's case is emblematic of the legal torments that journalists in Mato Grosso face.

Mendes' hostility against him, the journalist said, began in 2013, when the current governor was serving the first year of his term as mayor of Cuiabá.

“When he was mayor, in the first stories I wrote, I already noticed the animosity. In the first year, I wrote an article about a bid for a machinery lease that one of his partners won. Soon after, he cursed me at a press conference,” Aprá said. “It was crazy stuff. I realized that he did not accept being questioned.”

From then on, Aprá said, he began to receive “a rainfall of legal cases.”

"I think there are currently 15 cases filed by the governor, his relatives and secretaries,” Aprá said.

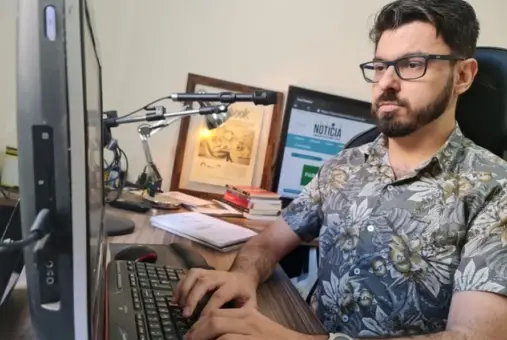

Journalist Alexandre Aprá, whose arrest was requested by the police department of Mato Grosso. The request was denied by the Judiciary (Photo: Courtesy)

In 2020, Aprá was convicted of slander (calúnia) for a news story published in February 2016. In the text, the journalist stated that an independent audit showed that the governor and the first lady allegedly transferred R$23 million (about US $4.6 million) to third parties and defrauded the process of judicial reorganization of Bipar, a company owned by him, harming creditors. Aprá began complying with his punishment in June 2023, with monthly payments of compensation.

Aprá said that Mendes tried to silence him not only through the courts. An example of what the journalist has gone through occurred in 2021 and earned the nickname “Caso Detetive” (Detective Case).

In June of that year, Aprá wrote a column for the site Isso é Notícia about a 2019 Instagram post by the state's first lady, Virgínia Mendes, in which she showed a photo of a ring and thanked publicist Ziad Fares.

From then on, Aprá said, he began to be pursued by private detective Ivancury Barbosa. Unaware that he was being recorded, the detective was filmed installing a tracker in Aprá's car. As reported at the time, in audio recordings with someone working for Aprá, the detective stated that he was hired indirectly to do the job for the first lady of Mato Grosso, and said that he intended to stage a crime in which the journalist would be arrested with drug dealers or with teenagers in a motel.

Aprá handed over the evidence to the Federal Police and left the state at the time, fearing for his life. The case was closed in April 2022 by the Mato Grosso Civil Police without any suspects being indicted.

Since September 2021, the Detective Case has been under the care of the Specialized Police Station for the Repression of Computer Crimes (DRCI).

The police station is at the heart of complaints of persecution made by journalists. According to the National Federation of Journalists (Fenaj) and the Union of Journalists of Mato Grosso, 15 cases against journalists in 2023 passed through the police station.

“Mendes always adopts the same strategy: he files the police report and directs the cases to the Station for the Repression of Computer Crimes, created by him under the justification of combating fraud and fake news. But in reality it became a political police,” Aprá said. “All of the governor’s complaints go to this police station, and the police chief carried out an investigation that was absolutely biased to favor the governor, in the sense of persecuting journalists who displeased the governor.”

A lawyer for some of the journalists claims that, in terms of procedures, the judicial procedures adopted contradict the usual practice of crimes against honor.

According to lawyer André Matheus, who works for the Journalists and Communicators Protection Network and represents six of the journalists prosecuted, in the case of crimes against honor, a category that includes cases of slander (calúnia) and defamation, when someone feels insulted, the person generally goes to a nearby police station. The police station then sends the case to a court, which holds a conciliation hearing, before opening a criminal complaint – a more serious type of complaint.

“Crimes against honor have not been investigated in police stations since 1995,” Matheus told LJR. “But they [Mauro Mendes and his lawyers] are introducing other types of criminal offenses to justify going to the DRCI and increasing the severity, such as criminal association and stalking. But writing an article does not constitute stalking.”

According to Matheus, the DRCIs, police stations specialized in computer crimes that have become more common in Brazil, are designed to combat “major crimes, such as extortion or embezzlement, and not crimes against honor.”

Another journalist investigated by the DRCI was Pablo Rodrigo.

Rodrigo told LJR that Mendes' animosity against him began in 2019, during Mendes’ first year as governor. The sentiment worsened in 2020, Rodrigo said, when he wrote an article with Lázaro Thor Borges for the website Congresso em Foco in which he cited a plea bargain from Operation Car Wash that mentioned an alleged bribe payment to Mendes in 2012.

“After this article, he started to get more annoyed,” Rodrigo said.

The situation, the journalist said, worsened in July 2023 when he published in the newspaper Gazeta Digital that Mendes' son, Luis Antônio Taveira Mendes, was one of the businessmen investigated by the Federal Police for allegedly purchasing mercury without legal authorization to use in mining in the states of Mato Grosso and Pará.

Four days after publication, on July 13, 2023, the governor and his son filed a criminal lawsuit against the journalist and the press outlet that published the story. In the lawsuit, they asked for censorship of the article; public retraction; apology; conviction of the defendants, payment of compensation for moral damages set at R$660,000 (about US $133,000), in addition to paying legal fees, court costs, and interest of 1% per month to be applied from the date of the publication of the story.

The journalist Pablo Rodrigo and the governor of Mato Grosso, Mauro Mendes (Photo: Rogério Florentino/ OD)

With interest, the lawsuit is currently for more than R$1 million (US $200,000), Rodrigo said.

“They used the argument of fake news, considered a computer crime, to judge it there. But how can a report published in a newspaper be a virtual crime?” Rodrigo said. “They are trying to criminalize professional journalism.”

Court filings confirm the investigation, although they do not specify details about the case.

Rodrigo also said that he receives messages “from third parties” suggesting he might be framed for a crime, such as a drug arrest.

“A lot of messages arrive. This harms our profession, including our relationships with sources. There are people who say ‘the guy is being wiretapped, monitored,’” Rodrigo said.

The biggest loss, however, is on a personal level.

“My biggest concern is for my wife and my son. There is an attempt at moral lynching. They tell me that I will undergo a search and seizure, that I will be arrested. Imagine your 13-year-old son seeing in the press that his journalist father lied,” Rodrigo said.

In his defense, the journalist obtained substantial evidence: in November, the Federal Police announced that they were investigating two companies in which Mendes' son is a partner for illegal trade in mercury, used to extract gold in the Amazon. The investigation is ongoing.

In the case of Enock Cavalcanti, it was an opinion piece that resulted in a case for criminal association, a request for arrest and a Civil Police raid on his home.

On his blog “Página do Enock”, the 70-year-old journalist writes articles about national and local politics. He reproduced the Repórter Brasil text, inserting comments before pasting it saying that the allegations deserved investigation, Cavalcanti told LJR.

“Judge Orlando Perri always had a reputation in Mato Grosso acting as an appellate judge fighting against corruption, we never had information that he worked in the mining sector,” Cavalcanti told LJR. “We asked Perri for explanations, because his name as a legal advisor appeared in a sector surrounded by many complaints. In Mato Grosso, mining appears more frequently on the police pages than the economy section.”

According to the search and seizure warrant, Cavalcanti's was suggesting in a text that has since been taken down due to court order, “even if indirectly, that there are illicit negotiations” between Mendes and Perri. To justify this, the Civil Police argued that the journalist wrote phrases such as “Perri owes society urgent explanations” and that the two may be “intertwined in the exploration of the rich mineral veins in Mato Grosso.”

On Feb. 6, at 5:40 am, six civil police officers showed up to seize his cell phone and laptop, Cavalcanti said. According to the journalist, he did not know which accusation motivated the search and seizure operation, and it took hours to find out.

The “biggest absurdity” of the case, Cavalcanti said, was the use of the police apparatus instead of private action.

“The absurdity is not a governor questioning a journalist, but questioning a journalist using the State structure. Mauro Mendes, instead of pursuing private recourse to question it, used six police officers to invade the home of a 70-year-old journalist who should be treated with greater respect,” he said.

One of the journalist's complaints is the lack of national and local repercussions the case has had.

“We are a periphery of Brazil, and who looks at the peripheries of Brazil? In all states, the main advertiser in most cases is the government. He holds the cash, and with that, he controls almost all the newsrooms,” Cavalcanti said.

In the same police operation, the third target was Popó Pinehiro, who is director of the site gw100.com.br and the brother of Emanuel Pinheiro, the mayor of Cuiabá and political rival of Mendes. In that case, police allege he shared the link to the story in a WhatsApp group. In the request made by the civil police, there is only a printscreen of a piece of news shared by Pinheiro in a WhatApp group, with the text “This news is in the top ten most viewed on UOL.”

There are also complaints of alleged sanctions taken outside of court.

VG Notícias, based in Várzea Grande and one of the four most visited sites in the state, claims to have had advertising funds unfairly cut.

The problems began, according to its owner, Edina Araújo, when the editor-in-chief published on the first lady's Instagram criticism of Mendes' wedding.

“One Saturday morning, I don’t know why, one of our employees decided to go on the first lady’s Instagram and wrote ‘forced marriage,’ with little disgusted emojis,” Araújo told LJR.

Soon the media outlet saw its advertising budget from the state dry up, Araújo said.

Then, according to Araújo, the state government began to no longer respond to requests for information.

“After that they started persecuting us. We ask questions in accordance with the Access to Information Law. They don't respond. We requested a version of the facts from other parties involved, and they did not respond. This leaves us vulnerable, as there is a risk of being accused of not seeking the other side, even though we have made efforts to do so,” Araújo said.

Araújo also said that, after reporting on the investigation related to the alleged illegal purchase of mercury by companies linked to the governor's son, she ended up being investigated by the DRCI.

“We do not spread fake news, on the contrary, we are a very responsible media outlet. However, it becomes infeasible to operate in a state governed in this way, where journalists are afraid to ask questions,” Araújo said.

In addition to the journalists mentioned above, there are also 13 others who face legal action after publishing about Mendes and his allies, according to Fenaj accounts: Victor Nunes, João Dorileo Leal, Maria Luiza Nogueira, Janice Ortis Ramos, Edivaldo de Sá Teixeira, Rodrigo Gomes Vieira, João Adevilson de Souza , Marcos Fabiano Peres Sales, Ari Dorneles Pereira, Haroldo de Arruda Júnior, Ulisses Lálio Pereira Barros, Daniel Pettengill and Hevandro Peres Soares.

On Wednesday, March 6, following a request for a preliminary injunction made by the defendants' defense on Monday, Minister Carmen Lúcia, of the Supreme Federal Court, suspended the court decision that supported the search and seizure operation, the breach of confidentiality and the removal of contents.

In the preliminary injunction, in addition to completely suspending the decision against Aprá, Cavalcanti and Pinheiro, Lúcia criticizes judicial restriction on the press.

“In addition to the curtailment on press freedom, there is, at least from the initial report of the factual and procedural situation made by the complainant, the impediment of his professional performance due to the search and seizure of devices linked to his professional conduct. And even more than that, the devices that would have been seized could reveal sources, in another contradiction to the constitutional system,” the injunction states.

Lúcia also defended press freedom.

“By ordering the court to search and seize journalists’ computers and cell phones and imposing the suppression of material with journalistic and informational content, the right to freedom of the press and of expression can be thwarted, inhibiting activities essential to democracy, such as it is political and investigative journalistic performance,” the text reads.

With the decision, according to lawyer André Matheus, the texts that were taken down must be republished, and the seized electronic equipment returned. According to him, the cell phones were returned on Friday night (March 8), and the computers are expected to be returned on Monday.

The lawyer considers Lúcia’s decision “paradigmatic.”

“The case will serve as a paradigm for other cases that attempt to violate source confidentiality,” he said.

The advocacy coordinator for Reporters Without Borders in Latin America, Bia Barbosa, told LJR that she considers the preliminary injunction “another action by the STF in defense of not only constitutional, but democratic guarantees, and the exercise of freedom of the press and journalism in the country.

Barbosa said “there is a very broad understanding in the preliminary injunction that the search and seizure and the existence of an investigation create restrictions on freedom, impede and constrain journalists. In the decision, Lúcia states that the press often deals with what governments hide. She has a broad understanding of the strategic importance of journalism for democracy.”

Before the decision, eight entities defending press freedom, including Fenaj, the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji), Reporters Without Borders, Article 19 and the Vladimir Herzog Institute published a statement critical of the operation against Aprá, Cavalcanti and Pinheiro, classifying it as “a serious violation of press freedom.”

On March 1, the case was analyzed by the Observatory of Violence against Journalists and Social Communicators.

Delegation of journalists from Mato Grosso before the hearing of the Observatory for Violence against Journalists and Social Communicators of the Ministry of Justice in Brasília; in the center, the National Secretary of Justice, Jean Uema (Photo: Sindjor/MT)

In November last year, Fenaj and the Journalists Union of Mato Grosso asked the Attorney General's Office (PGR) for federal intervention in the State and the removal of Governor Mendes due to recurring attacks on the free exercise of journalism.

The Journalists Union of Mato Grosso is working in four of the 18 cases. The president of the union, Itamar Perenha, said he believed that the objective of seizing cell phones and computers from Aprá, Cavalcante and Pinheiro was to discover the journalists' sources.

“When secrecy is broken, it is reaching all sources of journalism. Nobody uses a phone and throws it away like criminals. Journalists have the right to use source confidentiality,” Perenha told LJR.

The journalist criticizes in particular the imputation of criminal association, which he considers to have been used to justify the request for arrest that was denied by the courts.

“It is necessary to have a minimum of contextual elements to try to justify the opening of the investigation with the crime of criminal association. You need to have a boss, each with a role. If not, it is not an association, but a mess. There was nothing to justify it. They appropriated a criminal type to carry out investigations in other cases,” he said.

Matheus, the lawyer, also criticized the use of the expression fake news in investigations to silence journalists.

“In the recent past, there were many people spreading fake news in Brazil. But today they are using defensive jurisprudence to censor journalists who are telling the truth,” he said.

In her decision, Minister Carmen Lúcia gave a deadline of 48 hours for the Police Inquiries Center of the Judiciary of Mato Grosso to provide information about the case. When contacted by LJR, the entity only said that the case files are confidential and it will not comment on the case to the press.

Prior to the recent STF decision to grant the preliminary injunction, LJR consulted Mauro Mendes’ Office about accusations of misusing the public sector and persecuting journalists. It limited itself to saying in a statement that “just like any citizen, the governor has the right to seek the competent authorities when he is a victim of systematic crimes of slander (calúnia) and defamation.”

The Civil Police said in a statement prior to the intervention of the STF that investigations “to investigate the conduct of an alleged criminal association, responsible for the fabrication and dissemination of fake news and digital files, are ongoing.”

Regarding what elements there would be to attribute the crimes to the journalists, the Civil Police said that the questions are “in the context of the police investigation, which remains confidential, and no further information can be provided until the work is concluded.”

According to the agency, “numerous steps are taken during investigations, such as hearing witnesses and analyzing collected and seized materials. During the investigations, numerous pieces of information were collected that made it possible to establish connection and coordination between those investigated.”

The Civil Police also said that “all actions carried out to date have been analyzed and obtained a favorable opinion from the public prosecutor’s office and approval from the Judiciary. All requests made to the Judiciary are based on the records with an indication of possible criminal offenses.”

The Civil Police also said that “it will finalize the investigations and forward it to the State public prosecutor’s office and the Judiciary for assessment of the elements found and holding those investigated accountable. As provided for in the Brazilian legal system, the acts of the Civil Judiciary Police are supervised by the State Public Prosecutor’s Office.”

When contacted prior to the STF decision, the State Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPE) of Mato Grosso said in a written response that the “search and seizure measures were carried out following a warrant signed by the Police Authority and with a favorable statement from the public prosecutor’s office on the legal basis of article 240 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which authorizes the measure so that elements of conviction that are important to the investigation, elements of conviction that could not be collected by other means, can be collected.”

Asked about the need and purpose of breaking journalists' confidentiality, the entity stated that “the evidence found cannot be, FOR NOW, disclosed, because the investigations are under secrecy. However, what can be said, with certainty, is that the searches and seizures were intended to collaborate with the collection of essential information, which could not be obtained in any other way, such as electronic messages sent and received via email or through the WhatsApp application.”

According to the entity, “the intention of the search and seizure measure was never (and will never be) to offend the constitutional principle of protecting source secrecy; especially because the public prosecutor’s office does not condone any unconstitutional act, especially acts that violate fundamental rights and guarantees, as is the case with source confidentiality.”

The MPE also stated that “secrecy in search and seizure measures is enacted when the disclosure of information could harm the progress of investigations, given the possibility of evidence disappearing. However, it is imperative to remember that the public prosecutor’s office is an institution constitutionally responsible for defending the democratic regime and social and individual interests, therefore, of free expression of thought, not condoning acts of censorship.”

The public prosecutor's office also added that it acts “in each specific case with zeal and fearlessness, so that any attempts to intimidate or silence professional activities, notably those linked to freedom of expression, will be immediately repudiated.”

Finally, the entity said that, “according to Brazilian law, criminal investigation is the exclusive activity of the Civil Judiciary Police, however, the investigated party has access to the content of the investigation and, when secrecy has been decreed, this situation is always temporary, because every citizen under investigation has the right to oppose the evidence produced against him and to defend himself before the Police, as well as in court, since the Federal Constitution gives him the right to full defense and defense proceedings.”

After the statement is received from the Police Inquiries Center of the Judiciary of Mato Grosso, a appellate judge may dispute the STF's decision. It should still take at least a few weeks for a final decision from the Supreme Court on the search and seizure case.

Regarding the set of cases, André Matheus said he expected the journalists to be acquitted, because the court's jurisprudence tends to be in favor of press freedom.

“The Supreme Federal Court has had a very consolidated understanding of press freedom since ADPF-130, from 2009, when the Press Law was not sanctioned,” Matheus said.

Until that happens, however, journalists need to deal with the burden of being accused, with sources who don't want to talk, with fear and exhaustion. The process, in this case, is already a form of punishment.

“I spend the day looking for a lawyer, responding to cases, going to hearings. This is what my life has become,” Aprá said.