Twenty years ago, Brazilian newspaper EXTRA published a special six-page report that would capture the attention of Rio de Janeiro, the country and the world.

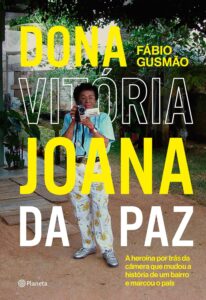

Joana Zeferino da Paz, who passed away in 2023 at the age of 97, is the subject of the rereleased book by Fábio Gusmão.

Journalist Fabio Gusmão told the story of Dona Vitória, an 80-year-old woman who, with courage and a camera in her hand, documented drug trafficking and police corruption in the Ladeira dos Tabajaras community, in Copacabana, one of the main tourist areas of Rio de Janeiro.

In his original reporting, as well as a book published in 2006, Gusmão refrained from using her complete name to protect her safety.

Her death in 2023, at the age of 97, has allowed the journalist to reveal her identity, ending almost two decades of secrecy.

Joana Zeferino da Paz’s recordings, made from the window of her apartment, were crucial to investigations that led to the arrest of 30 people involved in criminal activities.

With a cover that now bears the title “Dona Vitória Joana da Paz” and a photo of the story’s heroine with her camera, Gusmão’s book was recently re-released.

It introduces new developments, including details about Paz's life after publication of Gusmão’s reporting and her entry into the Witness Protection Program.

The new edition also includes exclusive images from the last few weeks of recordings from the window of the witness who had to spend years in exile to protect herself from organized crime. In the new pages, there are also transcriptions of Paz’s complete narration and revelations about the heroine's life behind the camera.

In an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR), Gusmão said that it took a year and a half from the discovery of Paz's records to the publication of his reporting. The team's main concern was the elderly woman's safety. Furthermore, as described in the book's preface, written by Otávio Guedes – former director of EXTRA –, upon listening to Paz’s narration, Gusmão was sure that the real story was happening inside the house and not outside the window. The case was about that woman's life and not the actions of the criminal gang.

Fábio Gusmão and Joana da Paz, protagonist of the article that marked Brazilian journalism. (Photo by Fábio Gusmão)

The case, Gusmão said, generated a profound ethical debate about the role of the journalist in stories of such social relevance, highlighting the care and commitment to the protagonist's safety. The new edition of the book reaffirms the importance of telling real stories that challenge power structures, and at the same time highlights the personal dramas of citizens who live alongside organized crime.

Dona Joana's story transcends journalism and has also conquered cinema. Soon, audiences will be able to watch her journey in the film "Vitória," starring Fernanda Montenegro, a wish of the late Paz. The premiere is scheduled for March 13, 2025.

With the relaunch of the book and the premiere of the film, Paz’s story is consolidated as a landmark in journalism. Her fight against crime and the impunity in the case was recorded by Gusmão, who, in addition to the empirical material and several hours of interviews and conversations with the main character, managed to carry out a parallel investigation into the gang that operated in broad daylight, corrupted and addicted children and colluded with police officers that were supposed to combat them.

This interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.

LatAm Journalism Review (LJR): How did Dona Vitória cross your path? How did you find this story?

FG: It was March 2004. I was a reporter and covered the police beat at the newspaper “Extra,” where I had started in February 1998, even before the newspaper was released on newsstands, when the team was still working on the project for a new popular publication.

I have always worked on police and security, with some sources, mainly in the intelligence sector. I went to the streets looking for a more elaborate story for the Sunday newspaper. At the Civil Police Intelligence Coordination, a police officer mentioned the visit of an 80-year-old woman who had left seven or eight tapes with recordings about drug trafficking and armed men in Ladeira dos Tabajaras, in Copacabana, in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. I saw the material. There wasn't much new in the images because we already knew it happened in Rio's favelas, but I was still interested because it was an upscale neighborhood in the city. The police officer explained that authorization would be needed to release the recordings.

Two weeks later, I got the tapes. Inside the bag, I found a card from the lady who produced the material. When I took the tapes home and turned up the sound on the TV, I realized something was different. In addition to the images, there was a powerful and vibrant narration from the resident. It was the narrative of her life, her daily life, her indignation. I spent the night decoding the recordings and I was sure: I was in front of the story of my life.

Marina Maggessi, the civil police officer who authorized the release of the tapes, set a condition for publishing the story in the newspaper: I could only publish the case in coordination with police investigations. She wanted time to investigate. The next day, in the newsroom, I spoke to my boss. The newspaper team loved the story and hired a production company to capture the images and extract frames.

LJR: How did the negotiation for publication, the contact with Dona Joana and your investigation into the case happen?

FG: The publication took a year and a half. Marina Maggessi was concerned about advancing the investigation, identifying people and avoiding criticism of the police's work. This lasted six months, but her team was transferred from the police station, and I was left with the story, aware that it was the biggest of my career.

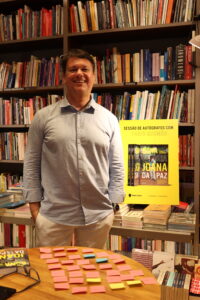

Journalist Fábio Gusmão reveals the true identity behind the name given to the woman who fought against drug trafficking in Rio de Janeiro from the window of her house. (Photo by Stella Daudt)

At the same time, I feared for Dona Joana's life. She had lived there since the 1960s, and had reported drug trafficking several times. When we finally met, it was at a police station. After gaining her trust I went to her house. When I entered the apartment for the first time, I saw the proximity of the boca de fumo [a place where drugs are sold] and I was sure that it would be impossible to publish anything without first ensuring her safety and getting her out of there.

I started visiting her regularly. For two intense months, when we drank coffee and ate cookies, we talked about her life. Time passed. In March 2005, I asked to resume the story, but on the condition that she leave the apartment before publication.

I started a parallel investigation to identify the criminals. The story was about her, but I needed to contextualize what it represented.

She agreed to leave the house, and the police Undersecretary of Intelligence used the apartment as a base for operations. The Public Prosecutor's Office included her in the Witness Protection Program, but she demanded to sell the property before leaving. After a long negotiation and police operations, she left the place.

In July, I had a formal interview with her and organized all the material. On Aug. 23, 2005, at 7 p.m., I started writing the six pages of the special report. At 11 p.m., I finished. Three editors reviewed the material, and at the end of the process, I burst into tears.

LJR: As a journalist yourself, you were somehow involved too, being part of that story, too.

FG: Since college, the ethics of journalists when getting involved in the news have been debated. My perception changed. The story was real, and protecting her life was not interfering; it was a question of humanity. I asked to include a first-person text in the publication of the case, explaining everything that happened and my feelings.

The morning after publication, the response was immense, with calls, emails and interviews. Fantástico, a TV Globo program, scheduled a meeting with her, and international media outlets began to report on the case.

LJR: With all these repercussions, what changed after all the work you did?

FG: Many professional colleagues told me that this was the story they would like to have told. For me, the main change was in the way I see people's stories. I started to look for their essence and understand how their complaints can gain strength when they are really heard.

The ethical debate remains, but I will always be in the same position: her life was non-negotiable.

LJR: How did you coordinate the process and deal with the daily demands of the newsroom?

FG: The anxiety was constant, especially with shootings that occurred close to her house. I told her to protect herself. I feared for her life. If any information were to leak, she could be at risk. On the other hand, I continued my life doing other reporting, but the case consumed my thoughts. Ten days before publication, I got another scoop: a police wiretap with the drug boss of Rocinha, a favela in the South Zone of Rio, talking to goalkeeper Júlio César, who was a member of the Brazilian football team.

LJR: And after publication, what was your contact with her?

FG: After a period of no contact, she left Rio de Janeiro for safety reasons. But I spoke to her a few times. She even left the Witness Protection Program. I convinced the prosecutor to reinstate her to the Protection Program when she left. However, when the book came out, she was upset because I changed details of her life, her name, to protect her.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a neighbor connected us via video. She was old, but still had good memories. When I learned of her death in 2023, I was shaken. I wrote her story as a tribute.

She knew that her story would also be told in a film and always dreamed of having her life represented by Fernanda Montenegro. Now, this story will be immortalized.

LJR: What changed in your career from then on?

FG: Everything. I won the biggest journalism awards and was promoted to editor. But the most important thing was telling a great story, one that still resonates 20 years later.