By Franz Chávez and Leny Alcoreza*

This is the second story in a series on protection mechanisms for journalists in Latin America.**

La Paz, Bolivia — Six journalists covering incidents related to the seizure of agricultural land in the province of Guarayos, Bolivia, were abducted on Oct. 28, 2021.

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez - Altais)

A group of hooded men with long weapons subdued the journalists, five men and a woman between the ages of 30 and 50, and held them for seven hours in the most violent attack on journalists in recent memory in Bolivia.

News of the abduction captured the attention first of the social networks and then of media and journalists' organizations that broadcast messages of denunciation and protest. This escalated to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and calls to establish a mechanism for the protection of journalists in Bolivia.

Bolivian journalists have not been immune to attempts at censorship or intimidation and the two years prior to the abduction of the six journalists saw an escalation of attacks, particularly in the wake of the political crisis that brought down the government of Evo Morales in October 2019.

In 2021 alone, the National Press Association (ANP, for its acronym in Spanish) of Bolivia, which has an aggression monitoring unit, documented 38 verbal and physical attacks against journalists.

But, the abduction of six people was an unprecedented event, revealing the deteriorating security conditions for Bolivian journalists.

So, as in other countries of the region, talks are underway to set up a protection mechanism for journalists that would limit violence against press professionals. Plans are largely under wraps at this point, but the violence against journalists that spurred them is in plain sight.

The abduction

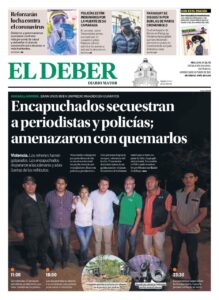

The front page of the newspaper El Deber of the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra shows the journalists and a police officer abducted by land invaders in the Guarayos province of the department of Santa Cruz, on October 28, 2021.

At the invitation of the National Association of Oilseed Producers (Anapo), an organization of agro-industrial businessmen, a group of journalists traveled to the Guarayos area, in central Bolivia, to verify the alleged occupation of lands promoted by sectors related to the party in government.

The region had already recorded violent incidents related to this land conflict. For example, one day before the journalists' visit, a group carrying firearms invaded the property called Las Londras and four agricultural workers were wounded as a result of the action.

For this reason, the journalists' visit was accompanied by a security force made up of police chiefs and agents, as well as agricultural workers in the area. About 800 meters (about 0.5 mile) from the occupied land, the police were talking with representatives of the occupants explaining the reason for the visit, but they were ambushed by armed hooded men, according to the account of the television network cameraman Roger Ticona.

The visitors were in passenger buses and the assailants forced everyone to get off.

“They took us off the minibuses. I was in the last vehicle and when I saw what was happening, I ran to the mountains together with the driver of the truck in which I was riding,” Ticona told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). He said he managed to be evacuated from the region in a small plane provided by the farmers.

Six colleagues did not have the same luck and were held by the armed group: photographer Jorge Gutiérrez from the newspaper El Deber; reporter Silvia Gómez and cameraman Sergio Martínez, from the private television network Unitel; reporter Mauricio Egüez and cameraman Nicolás García, from the television network Uno, and cameraman from the network ATB, Percy Suárez.

After her release, Silvia Gómez told the newspaper El Día: “We were held hostage for seven hours. They had long guns that they used to shoot at our cameras and the vehicles that transported us.”

“They beat us with sticks and we were kicked. Then they took us to a shed where there were about 80 hooded men who continued to beat us; they threatened to burn us with gasoline; They asked us who sent us and how much they paid us.”

Cameraman of the ATB television network, Percy Suárez, shows the impact of the bullet on his video camera that was left unusable.

Credit: Guider Arancibia – El Deber

Percy Suárez, a cameraman for the private television network ATB, recounted to LJR how he was forced to lie face down on the dirt floor, and one of the attackers destroyed the video camera with a precise shot from a shotgun.

But despite the damage to the equipment, Suárez managed to rescue the digital memory stick where the scenes of the assault were recorded. The image broadcast the next day by different media remained as an irrefutable testimony of the violence.

The news of the abduction was revealed immediately thanks to the fact that Roger Ticona had managed to escape. Journalists and citizens joined in calling for the government to intervene immediately, and this clamor was probably the reason the journalists were released just seven hours later.

Outrage

Indignation among Bolivian journalists over the abductions triggered a protest that caught the attention of the United Nations, after the Association of Journalists of Santa Cruz, the department where the abductions occurred, demanded an investigation from the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The abduction also prompted the launch of an initiative to create a protection mechanism for journalists, given the seriousness of the attack, which had not been seen in the recent past.

Since Bolivia had experienced a political crisis two years earlier, the country was under the spotlight of international organizations and in November 2020 the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights formed an Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) to investigate acts of violence in the months before and after the elections that year.

Because this violence had affected journalists, the GIEI recommended the creation of a non-state entity "to provide support and legal, administrative and psychological assistance to journalists whose rights are at risk of being violated."

The recommendation arose after an eight-month investigation carried out by the GIEI on acts of violence recorded before, during and after the general elections of October 2019 that were annulled due to allegations of fraud and ended with the resignation of President Evo Morales (2006 -2019).

The Monitoring Unit of the ANP recorded, between October and November 2019, a total of 89 attacks against journalists and 16 media outlets that covered the conflicts in departmental capitals and rural towns. That was more than half of all aggressions recorded in that year.

A hooded man points to the camera of the private network ATB during the abduction of journalists, on Oct. 28, 2021 in the Guarayos province of the department of Santa Cruz. Credit: ATB Network

Since November 2019, after the elections but before the GIEI began working in Bolivia, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights sent a technical mission to Bolivia to collect information on human rights violations and arrived at the same conclusion as its counterparts from the IACHR.

A report from this mission issued in 2020 recommended “promoting a safe and favorable environment for human rights defenders, social leaders, journalists and other social actors, including the systematic and public condemnation of any act of intimidation against them and the establishment of a protection mechanism endowed with sufficient resources that guarantees the safety of those people who are at risk.”

This report initiated a consultation process of the Technical Mission with journalists, press organizations and unions, to collect opinions about the risks that journalists face and the types of protection they require during the coverage of conflicts.

It is a process that is still ongoing and its conclusions have not been published, so it is not yet known what form this mechanism would take or if it would be modeled on experiences in other countries.

Participants in the consultation process include journalists attacked in the past year, representatives from media workers unions, leaders of journalists associations, academics specializing in freedom of expression and leaders of non-governmental organizations working in this field.

For Bolivian journalists, it is an advance to stop the wave of attacks of recent years, since most have gone unpunished.

Before the abduction

The abductions of the journalists in Guarayos was not the only attack in 2021. During the year, the Monitoring Unit of the National Press Association reported a total of 38 verbal and physical attacks on reporters and cameramen, and no case has been investigated by the public prosecutor’s office, according to the ANP’s records.

Several of these attacks happened during reporting and were at the hands of security forces.

Of these, another worrying case is the violent attack by riot police and the subsequent detention of Carlos Quisbert, a journalist from the newspaper Página Siete, in the midst of protests carried out by coca farmers from the Yungas region.

On Tuesday, Sept. 21, Quisbert was covering the clashes between farmers and police in La Paz. While he was recording images for his reports, a policeman ran over him with his motorcycle and the journalist reacted to this by protesting the aggression.

Immediately, about eight policemen equipped with anti-riot gear rammed the journalist, spraying him with tear gas and handcuffing him to a police van, according to Quisbert.

After protests from his colleagues, he was released for a few minutes, and again detained and taken to a police station where he remained for several hours.

Authorities did not respond to requests for comments about reported police violence against journalists.

Quisbert was consulted for this report on the impunity from the attacks he suffered.

“The police, politicians, officials and many times people who participate in street protests go unpunished after attacking journalists due to the lack of representation of leaders, media owners and union institutions that do not seek effective punishment of the aggressors,” he told LJR.

The 2019 crisis

The general elections of October 2019, questioned by opposition parties to the then-president and candidate for the Movement for Socialism (MAS), Evo Morales, sparked protests in the main cities of Bolivia.

A 20-day civic strike in the city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra and demonstrations in the cities of Potosí, La Paz and Cochabamba sparked a political crisis that led to the resignation of Morales on Nov. 10, 2019, and his hasty departure from Bolivia and refuge in Mexico.

The types of attacks that occur around elections and protests frequently create a risky situation for Bolivian journalists: reporting on political or social conflicts when they involve security forces or groups of protesters.

Between October and November 2019, journalists covering demonstrations or vote counts were the target of verbal attacks, stigmatization and because of their status as media representatives. This period became one of greatest hostility toward the work of reporters and the media.

During the counting of votes in the cities of La Paz and Cochabamba, journalists and cameramen were beaten by police and supporters of the parties in the electoral race, according to data from the ANP Monitoring Unit.

The television cameraman for Red Uno of the city of Cochabamba, Alejandro Camacho, appears during his recovery after being hit by a tear gas projectile while covering clashes between supporters of political parties, on Oct. 21, 2019.

Two days after the elections, on Oct. 22, a correspondent for the newspaper El Deber, Humberto Ayllón, was injured in the head by the impact of a tear gas grenade launched by the police. The journalist was covering the clashes between demonstrators who reached the gates of the Departmental Electoral Tribunal in the city of Cochabamba.

A day earlier, the television cameraman for the private network Red Uno in Cochabamba, Alejandro Camacho, suffered head injuries and lost consciousness after being hit by a police tear gas projectile. It’s unclear if the projectile was aimed at him or if he was hit randomly.

On Monday, Oct. 28, photojournalist for the newspaper La Razón, Miguel Carrasco, was hit by a stone that caused a head injury. He was covering the confrontation between people blocking a street in the Calacoto neighborhood of La Paz, and militants of the ruling party.

Police officials did not respond to inquiries about these aggressions.

Photojournalist from the newspaper La Razón de La Paz, Miguel Carrasco, appears with a bloody face after being hit by a stone during the post-election conflict of October 20, 2019, in Bolivia. Photo credit: La Razón

Aggressions were also directed at journalists from state media and those affiliated with the ruling party. The television channel BoliviaTv and Radio Patria Nueva suspended broadcasts on the afternoon of Saturday, Nov. 9 after demonstrations by groups of people who requested the cessation of broadcasts of both media.

The director of the radio station of the Trade Union Confederation of Farm Workers, José Aramayo, was tied to a tree and threatened with a dynamite explosion by residents of the Miraflores area of the city of La Paz.

Argentine press correspondents who covered the conflicts in La Paz took refuge in their Embassy after being harassed by demonstrators during their reporting.

Case goes unpunished

The October 2021 abduction was relevant not only because of the nature of the attack, but also because it was of a type not seen before in Bolivia. If the previous attacks had been in the context of protests and in many cases carried out by the police, in the case of Guarayos, the attack took place during reporting when the journalists were protected by the police.

However, in all cases the common denominator is that journalists have become the target of violence, either by the security forces or by political or social groups.

Meanwhile, the case of the abduction in Guarayos remains unsolved in the police and prosecutor's files. It joins dozens of cases of attacks on reporters that remain unpunished.

To date, only two people have been detained and sent to preventive detention for their alleged participation in the attack on press correspondents. During the abduction, the violent group hid behind hoods and used hunting weapons that in some cases fired projectiles that damaged television cameras.

Pensive as if anticipating a day in which his life would be in danger, El Deber photographer Jorge Gutiérrez appears in the aircraft that was transporting him to Guarayos. Credit: Jorge Gutierrez

In recent weeks and after complaints of fraudulent actions, the public prosecutor’s office triggered the detentions of judges committed to the release of people convicted of femicide, in an action aimed at recovering the image of a deteriorated justice system.

“I feel a great disappointment because while the Bolivian judiciary expedites other cases, the abduction case seems to be as it was at the beginning. And it would not surprise me if in a few weeks the two identified as having been at the scene with weapons and who were imprisoned appear free on the streets, as if nothing had happened,” photojournalist Jorge Gutiérrez, one of the victims of abduction, told LJR.

"I hope I'm wrong, but the feeling I have is that the guilty are not going to be punished," he says.

The prosecutor’s office has not given any updates on the case.

"When I spoke with the judge, I told him that apparently one of us needed to come out wounded or dead from the jungle for this process to move forward. The images that I managed to take of people armed and shooting are convincing, but not even with such evidence was anything acted upon," Percy Suárez said in an interview with LJR.

The organization that represents the main Bolivian newspapers, the National Press Association (ANP) issued a statement on Feb. 6, and expressed concern about "the lack of progress in the investigations into the abduction and torture of journalists, and noted its protest over the changes in prosecutors and investigators.”

*The authors of this article, Franz Chávez and Leny Alcoreza, are Bolivian journalists and direct the Monitoring Unit of the National Press Association. The ANP is participating in the talks about the protection mechanism.

**This is the eighth report in a project on journalist safety in Latin America and the Caribbean. This LatAm Journalism Review project is funded by UNESCO's Global Media Defense Fund.

Read the rest of the articles in this project at this link.