“El Ñacas” and “El Tacuachi” are two hitmen from the state of Sinaloa, Mexico, who bounce between drug trafficking, politics, business and domestic problems just like anyone else, according to the words of their creator. They are two fictional criminals who carry out their misdeeds with impunity and cynicism, portraying the alternative culture that has emerged from the presence of organized crime in that country.

The characters are the protagonists of a popular comic strip created by cartoonist Ricardo Sánchez Bobadilla that is published in the weekly Ríodoce, a Sinaloan media outlet and winner of the 2011 Maria Moors Cabot Prize.

Bobadilla and other Mexican cartoonists use humor and drawing to mock narco culture and organized crime in Mexico, while making visible the tragedy and surrealism of drug trafficking and criticizing the inefficiency of authorities to combat it.

"El Ñacas y El Tacuachi" has been published in the weekly Ríodoce since 2010. A few years later it was published in the political satire magazine El Chamuco. (Photo: Courtesy Ríodoce)

“El Ñacas y El Tacuachi” emerged in 2008, when Bobadilla and a group of Sinaloan cartoonists founded the magazine La Locha. At that time, then-president Felipe Calderón had started a war against the drug cartels that unleashed a wave of violence that persists to this day. According to Bobadilla, the founders of the magazine noticed that drug trafficking was a daily feature in the local media, but it was always addressed in the pages of la nota roja, a type of journalistic coverage emphasizing the violent nature of crime.

“When we started making cartoons addressing the issue of drug trafficking, what we wanted was to make it visible. Narco culture is there and we take those elements to create humor and make visible that there is a problem,” Bobadilla told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “One of the important functions of the cartoon is to trivialize it a little, which I think happens when you laugh at something, and in this case it also [serves to] cope a little with the tragedy.”

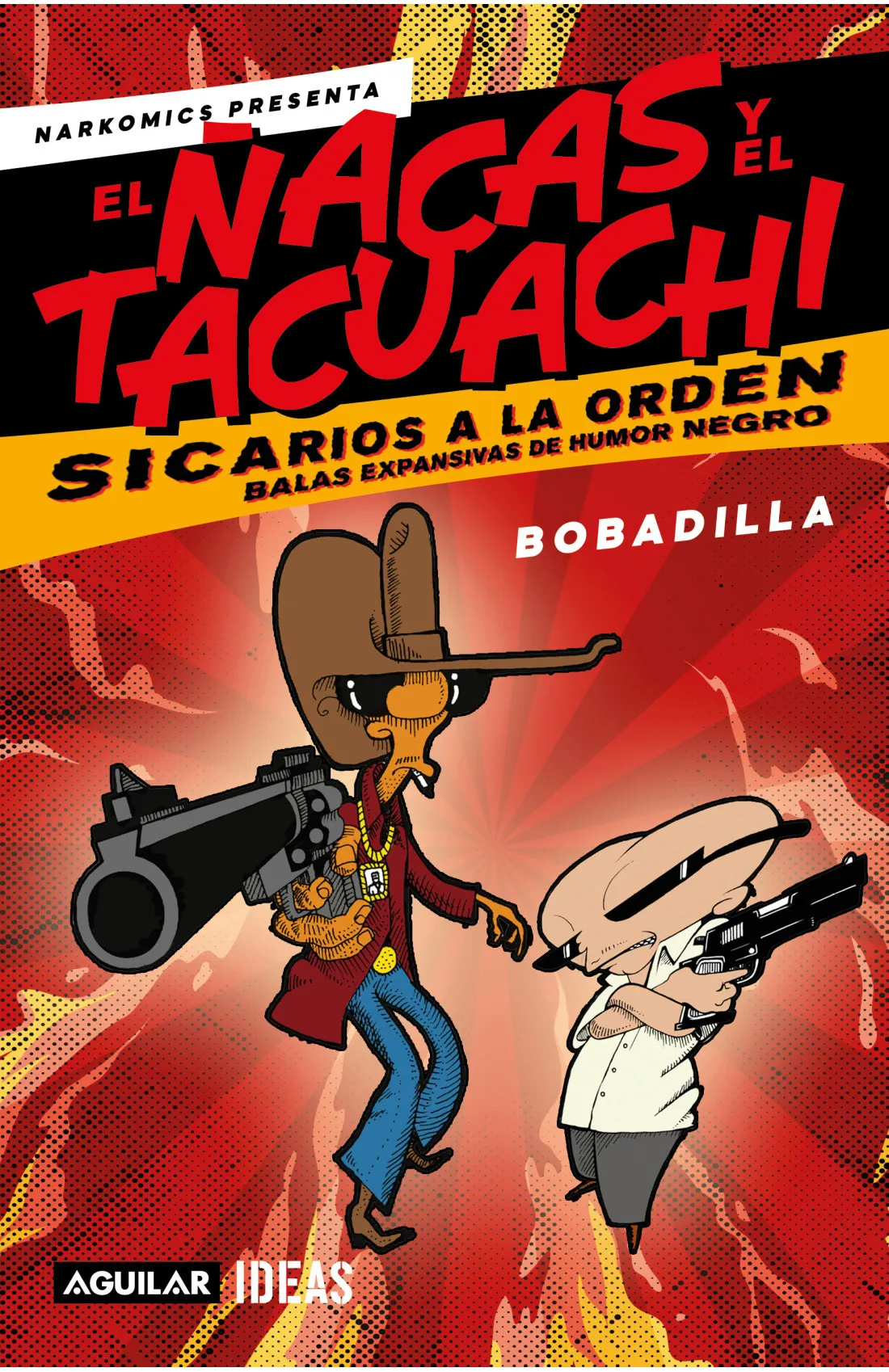

“El Ñacas y El Tacuachi” arrived at Ríodoce in 2010 and a few years later Bobadilla was invited to publish his comic strip in the political satire magazine El Chamuco, which has national reach. And in 2023 the characters arrived in the world of books with ““Narkomics presenta: El Ñacas y El Tacuachi. Sicarios a la orden” (Narkomics presents: El Ñacas and El Tacuachi. Hitmen at your service), a compilation with the most popular installments of the cartoon.

Among the elements of narco culture that Bobadilla uses to satirize members of organized crime in his cartoons are their clothing, their way of speaking, their way of excess, their extravagances and their exuberant women, among others.

“It would be very bold to say that in the matter of drug trafficking there are humorous bents, but the truth is that there are, because it is also a cultural phenomenon where there is everything: ways of speaking, music, fashions, etc.,” Patricio Ortiz, another Mexican cartoonist who addresses the issue of drug trafficking in his drawings, told LJR. “All of that is what I get into most, in that cultural issue that does have many humorous veins.”

Patricio, as he is known, is one of the founding members of El Chamuco. It was he who proposed to Bobadilla to publish “El Ñacas y El Tacuachi” in the magazine when he realized that the situations in Sinaloa portrayed in the comic strip were repeated in other states of the country, so he thought it was important to give it visibility at the national level.

The main objective of cartoons is precisely that: to denounce and criticize power, according to Francisco Portillo, a professor specialized in political cartoons at the College of Political and Social Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. And it is not only about criticizing official power, but also the de facto powers, as many consider drug trafficking.

“That power can be governmental, it can be economic, it can be political, or any other type. If there is something wrong in society, criticism can be made with a cartoon just like it can be done with an opinion article,” Portillo told LJR.

The cartoon that mocks elements of narco culture carries implicit criticism of the authorities who have not managed to effectively combat the problem and have allowed the situation to go so far, the professor added.

Bobadilla published the book "Narkomics presenta: El Ñacas y El Tacuachi. Sicarios a la orden," a compilation with the most popular installments of the cartoon. (Photo: Courtesy Bobadilla)

“Criticism of the government, the State, the authorities in charge of combating drug trafficking and the ineffectiveness they have in terms of being able to reduce it in the way that society would like is legitimate,” he said.

Another comic strip that satirically portrays narco culture is “Quica y Pimpón,” by cartoonist Antonio Helguera, two-time winner of the Mexican National Journalism Award who died in 2021. The cartoon, which tells the anecdotes of an almost deaf and blind old woman and her drug trafficker nephew, is based on situations that Helguera heard in Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco, a city marked by violence for allegedly being part of a region disputed by two cartels.

“Everything he portrayed was basically what he heard from his neighbors. He basically portrayed what was happening around him and that is exactly so surreal, that he had no choice but to portray it,” journalist and cartoonist Rafael Pineda, known publicly as Rapé and director of El Chamuco, told LJR. “Antonio Helguera published some extremely powerful cartoons in the journalistic sense [...]. They were cartoons that are going to be in the history books of what happened with drug trafficking in Mexico.”

Rapé said that humorizing tragic situations such as drug trafficking responds to a human dynamic of laughing at misfortunes to better deal with them. But he also said it is part of the artistic and cultural tradition that exists in Mexico around death.

In the field of cartoon, Rapé said that this tradition dates back to José Guadalupe Posada, the 19th century lithographer who popularized “calaveras” or “catrinas,” drawings of skeletons in elegant outfits that are currently part of the folklore of the Day of the Dead in Mexico. Posada worked as an illustrator for publications aimed at the working class and used drawings of skulls to make social criticism.

“The tradition of cartoons that we inherited from Posada must also be taken into account: laughing at death has been part of our tradition of life,” Rapé said. “There is a whole series of events and human manifestations around drug trafficking and death in Mexico that do surprise me. There are people who condemn this type of work, but as a cartoonist, knowing the history of Mexican political cartoons in this country, I understand it perfectly.”

Cultural products that address the issue of drug trafficking, such as songs, films and television series, are frequently accused of advocating organized crime. And the political cartoons that address the issue have been no exception.

But, unlike television series and songs that portray drug traffickers as heroes, the cartoonists interviewed said that their strips and cartoons do not praise these characters. On the contrary, they make fun of them and the culture around them.

“It is very difficult for someone, after seeing Bobadilla's book, to want to be a drug trafficker because basically it is very funny, very ridiculous, very absurd humor that does not fall into the same category as narco-series,” Patricio said. “In my case, I make fun of the values of the drug world, which are absolutely ridiculous: women who’ve had plastic surgery, music, narcocorridos and ostentatious living and so on. My job is to make fun of all that.”

The cartoonists who draw about drug trafficking are aware of the danger that addressing aspects of organized crime in Mexico represents for journalism. Since the start of the war on drug trafficking in 2006, more than 130 journalists have been murdered in that country, according to figures from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

However, unlike journalists who report on criminals and cartels, cartoonists avoid making specific references to bosses or criminal groups that could put them in danger.

“Rather [what we portray] are themes, they obviously have to do with violence. Even when there is a particular situation that I am touching on, I refer to the situation, but I do not refer to the cartels or the characters,” Patricio said.

Bobadilla lives and works in Sinaloa, a state considered one of the epicenters of drug trafficking in Mexico and the place of origin of the cartel of the same name whose leader was Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

He has experienced drug trafficking violence against journalists very closely. The first media outlet where he worked as a cartoonist, A Discusión, experienced the abduction and murder of its director, journalist Humberto Millán, in 2011. In 2017, when he was already working at the weekly Ríodoce, co-founder of the media outlet, Javier Valdez, was killed. And in 2022, Luis Enrique Ramírez, a columnist for El Debate, another of the media outlets where Bobadilla publishes political cartoons, was murdered.

“In all the media in which I have worked there has been some event of violence against journalists. […] I am very aware of the danger of publishing in local media,” Bobadilla said. “Imagine Javier [Valdez], who had already received an international award, who was already recognized and appeared in national media, they murdered him without any regard… Imagine any journalist here. We really feel vulnerable.”

Several cartoonists who draw political cartoons about drug trafficking publish their work in the Mexico City-based magazine El Chamuco. (Photo: Screenshot of El Chamuco)

Bobadilla is originally from Tierra Blanca, one of the neighborhoods in Culiacán with the greatest movement of criminals and drugs. For the cartoonist, that means that at any moment he can run into members of organized crime.

“I remember that Maestro Helguera drew ‘Chapo’ dressed as a woman, as a prostitute. We could never do that here, because we could go across the street and we could come across the guy, or his henchmen,” Bobadilla said. “I know they read me, because Ríodoce is a newspaper that drug traffickers read. They are written about there, they are reflected.”

According to Rapé, those who the cartoonists should point out by name and surname – just as a journalist does in an article – are the authorities responsible for the fact that drug trafficking continues.

“That is the main responsibility we have, to point out who is to blame for drug trafficking being so embedded in Mexico,” Rapé said. “It would be extremely dangerous for us to make fun of a drug trafficker, but who is to blame for that? Well, the authorities that continue to allow it, well, we must continue pointing it out."

The political cartoon in Mexico has a leftist tradition, according to Bobadilla. Many of the most respected cartoonists of recent decades in that country, such as Rius, Helguera or El Fisgón, have emerged in media considered leftist, such as the newspaper La Jornada or the magazine Proceso.

However, the polarization that has worsened under the mandate of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has led some cartoonists to take sides in the confrontation between those who criticize and those who defend the government.

“There are still very good cartoonists on both sides. However, I believe that this passion and this brutal polarization has generated a phenomenon that seems quite regrettable to me, that you are on one side completely or you are on the other completely,” Patricio said.

In the midst of this confrontation, the humor of the cartoon and the comic strips has been the main victim, he added.

“With this polarization that generates a lot of bitterness, much of the humor in cartoons has been lost,” Patricio said. “Cartoonists are more focused on making their enemies angry than on taking advantage of some opportunities to [portray] humor and absurdity.”

This division is interesting, but dangerous, Bobadilla said, due to the level of influence that a genre of opinion such as political cartoons can have, especially in the current era, a few months before presidential elections and a change of administration in Mexico.

“I believe that there is a media fight and right now an electoral fight that involves them [the cartoonists] as opinion makers and that they have a lot of influence,” Bobadilla said. “A single cartoon can tell you many things, more than an opinion column can tell you. This polarity makes you reflect.”

Rapé said that there is a risk that, in the midst of the current political and ideological climate in Mexico, political cartoons lose their journalistic responsibility. Like all types of opinion, he said, political cartooning must be backed by editorial rigor.

“The only thing I hope and wish is that the very important need to make very well-informed, well-thought-out cartoons is not lost, and that it does not fall into historical or journalistic lies,” he said. "The opinion must be worked on slowly, it cannot be something reactionary, it has to be something that must be reviewed, it must be corroborated, it must be read, thought and in this case, drawn, very carefully."