Amid the scarcity of journalistic publications dedicated to culture in Brazil, two such media stand out for their longevity and method of financing – a state publisher that decided to invest in journalism, and, with public funds, has been doing so consistently for decades.

Created in their first versions, in 2000 and 1986, respectively, magazines Continente and Pernambuco (formerly Suplemento Pernambuco) are publications from Cepe (Companhia Editora de Pernambuco), a publisher that is also responsible for publishing the Official Gazette of the State of Pernambuco. Linked to the state government of Pernambuco, the organization also publishes books on literature, art and essays.

With a national reach and without equivalent in the country, the magazines have a new look. In June last year, journalist and anthropologist Mário Hélio Gomes, founder of Continente, took over editing both publications, following the change of state government in January 2023.

There were reforms, such as the merging of teams and a reduction in permanent employees. Furthermore, Pernambuco became a magazine instead of a literary supplement in the newspaper format, and its edition count, previously at number 213, was reset to zero. Previously with an openly left-wing editorial line, it now has the comprehensive slogan “magazine of literature, books and reading.”

Beyond national audiences, Continente also wishes to reach international ones, and has thus become bilingual, and now also publishes quarterly. There were also adaptations in the editorial line, no longer dealing only with cultural works and now encompassing, according to its editor, “a comprehensive understanding of culture,” also including, for example, tourist topics.

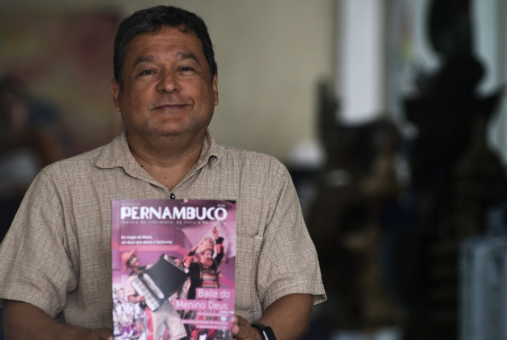

Journalist and anthropologist Mário Hélio Gomes, the new editor of Continente and Pernambuco magazines (Photo: Courtesy Leopoldo Conrado/Cepe)

The objective of both, according to Gomes, is to reach broad and plural audiences.

“A publication made by the government has to be plural, encompassing many forms of thought. The world has become black and white, and that is why it is even more important to be truly plural,” he told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “The important thing is that the reader has good taste and wants to be civilized. Books, newspapers and magazines are civilizational achievements and have an educational role. Not in the doctrinal sense, but in the sense of opening our eyes to a critical awareness.”

The projects, however, are not immune to criticism. In their new incarnations, the magazines made strong breaks with previous versions, and some say run the risk of losing important achievements, such as their captive audiences or national relevance. Others say Pernambuco's design and editorial line are more conventional, while Continente, by targeting an international audience, risks assuming an advertising rather than journalistic tone. Furthermore, some of those who previously worked at one of the magazines have warned about political influence in its pages in the past.

Pernambuco's changes correspond to the third phase of the publication, originally created in 1986 under the name Cultural Supplement of the Official State Gazette. This period lasted until 2007, when the literary newspaper called Suplemento Pernambuco was born.

Now looking like a magazine, with the price of R$10 (about US $2) per issue and monthly frequency maintained, the publication now has 72 pages per edition, a significant increase compared to the standard of 32 in the previous version.

The relaunch edition, with number 0, came out in December last year, and since then there have been two other issues. The covers focus on themes such as the art and profession of translation, the Christmas show "Baile do Menino Deus," by Ronaldo Correia de Brito, Assis Lima and Antonio Madureira, texts by the painter from Paraíba based in Pernambuco João Câmara.

In addition, there was the publication of extensive features on Arthur Rimbaud, hip hop and on José Cláudio, a visual artist from Pernambuco who died in December.

The January edition of Pernambuco magazine, dedicated to the writings of the painter João Câmara

The ambition, according to Gomes, is to focus, in addition to literature, on “the entire production chain of the publishing and book market, as well as public policies on books.”

“The magazine covers the literary world, books, libraries, publishers, but we also want it to consolidate itself as an instrument of public policy, to think about this chain. Being a government magazine, I think we have a social and cultural responsibility,” he said. “But it is also a magazine of literature because it is open to literary creation. Everyday there is less space for those who write short stories or short essays, and we offer this space.”

So far, there have been a preponderance of renowned artists and themes linked to the state of Pernambuco and its capital, Recife. The break with the previous administration is evident, when the supplement prioritized non-canonical writers and directly political contemporary themes.

Schneider Carpegianni, who was editor of the supplement from 2014 to 2022 and adopted the editorial orientation that gave the publication national relevance, being distributed in 12 capitals, told LJR that, in his management, he “had absolute editorial freedom to deal with what was happening in Brazil at the time and to take a political stance.”

“I took over the magazine when the fourth wave of feminism, the Black and trans movements, but also fascism, were gaining strength,” he said. “The supplement then had this very political brand, with a very left-wing position. It was supposed to be really left-wing, I'm totally against the idea that there is objectivity in journalism. Journalism does have a side, and we needed to stand against fascism. The supplement fulfilled its role very well, it was possible to use the outlet quite freely.”

His replacement Gomes classifies the editorial line that preceded him as “woke culture.”

“There was an agenda related to woke culture, this culture in which minorities have special relevance. There were stories related to feminism, gender identities, sometimes with ultra-specific concerns. They defended the issues in an almost militant way, with a line of activism,” Gomes said.

“In my understanding, this subject is as valid as any other. We don't say now that we're going to deal with the opposite of that, all of that remains a topic of interest. But it is one issue among others, it is no longer as dominant, as absolute, as it was for almost a decade. We understand that literature is very varied, and involves a lot of things.”

In the case of Continente, according to Gomes, the intention is for “culture to be understood in the broadest way possible.”

“We understand culture in the anthropological sense, as behavior, as a complete human sense and not just an artistic one,” he said.

This journalist's return to publishing takes place more than 20 years after his first stint. When he founded Continente, whose first edition came out in December 2000, he stayed there for two years and two months. The adjective “Multicultural,” which was part of the publication’s beginnings, returns as a complement to the official name.

Pianist Amaro Freitas, one of the greatest jazz musicians working in Brazil, appears on the first cover, and in an extensive report on contemporary music in Pernambuco, heir to the old “Continente Documento” section, which delved deeply into one topic. There are also reports on topics such as the presence of cangaço in cultural works and the so-called Hippie Trail that leaves Europe towards Nepal and India.

Brazilian Jazz pianist Amaro Freitas on the cover of the single new edition of Continente magazine

Alongside the eminently journalistic themes, there are others of a more advertising nature linked to the state of Pernambuco, such as a text about the Suape Industrial and Port Complex – the fifth largest port in the country –, and another about the paradisiacal island of Fernando de Noronha.

Gomes makes no secret of the fact that one of his intentions is to sell the image of Pernambuco, which is why the magazine is also published in English, making it 196 pages long.

“In the case of the printed magazine, Cepe is working on partnerships so that the magazine can be distributed on flights, including to encourage the more touristy part. We will continue to do tourism articles,” he said. “But we will also continue to sell at newsstands and bookstores, in the traditional way.”

According to the journalist, when the publication's new website is up, “the project will become clearer.” The intention, he said, will be to update the website weekly. There is also an app being produced, he said.

Regarding the themes covered in the two publications, despite the preponderance of artists with ties to Pernambuco, the editor denies that the magazines will be limited to the state.

“What I say simply is that it is the themes that define the choices, not geography,” he stated. “Of course, as there are important things happening here, we will also cover them. Pernambuco is as national as São Paulo, but, due to the economic importance that the latter has assumed and a process of self-colonization, what happens in São Paulo is considered to be of national relevance, and what happens in Pernambuco, regional.”

The changes arouse reluctance among some readers and former employees. Now a professor of social communication at the Federal University of Pernambuco, Eduardo Cesar Maia joined Continente in 2003 as an intern. He stayed there until 2011, serving as writer, assistant editor and editor of some editions. Until last year, he published sporadically in the magazine.

A specialist in the relationship between literary criticism and journalism, Cesar Maia said he fears that journalistic acumen and criteria are being left aside in both magazines.

“In relation to Continente, there is an attempt to return to a past era, a very old one, like 2002 and 2003. There are very abstract editorial lines and it seems to me that it is no longer a journalistic thought that is behind it, but rather an interest in thinking about themes in an academic sense. The feeling is that many texts no longer comply with journalistic demands,” he told LJR.

Cesar Maia said he was particularly concerned about the text about the port of Suape, which he considers propaganda disguised as journalism.

“If you have an order from the government to do an article about Suape, you put it out as advertising, and don’t try to disguise it as an article, because it isn’t,” he said. “It seems like it’s a magazine made for tourists, that wants to sell the state’s good things to an audience that isn’t even from here, saying ‘Pernambuco is wonderful.’”

The danger, he added, is that Continente, which had been closely following local and national cultural production, “ends up becoming a catalog magazine of good things from Pernambuco.”

“It is the opposite of the project that Continente was building, a project of critical cultural journalism, which examines cultural production from a critical point of view, instead of being a menu of good things for tourists,” he said.

Regarding Pernambuco magazine, Cesar Maia says that he had criticisms regarding the previous project, which he considered to be not very pluralistic and too biased in political terms for a public publication. However, he fears that the publication will lose relevance.

“From the point of view of publicizing the name of Suplemento [Pernambuco], Schneider’s [Carpegianni] work was extraordinary, he got great writers, transformed the publication into a very attractive product for our time, managed to make Suplemento surpass Continente from the point of view of public interest,” he stated. “But I find orientation of a primarily political nature, whether left or right, problematic.”

Cesar Maia said that, as some collaborators remained, it is still possible to find stories based on the previous incarnation. The researcher's criticism of Pernambuco is its visual language, which he considers outdated.

“The design of a cover immediately took me back to 2004. In visual terms, the feeling is that the new administration thought of resuming an old project. This impression was very bad. It’s legitimate to want to do something different, but not go back in time.”

One old edition of the now-extinct Suplemento Pernambuco with the cover dedicated to French philosophers Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze; the title says 'the anti-fascist life'

Regarding the criticism of the perceived lack of journalistic criteria, Gomes refuted the argument and returned the accusation: “It is obvious that the magazine in the previous model had a more academic touch, but in fact it was less journalistic than in the new model. We seek to have a broad approach to culture,” he said.

According to him, the proposal is to have “an absolutely diverse cultural approach, and this will show in practice. This means understanding culture in the century we are in, in all its scope, which includes good things and tourism.”

Gomes added that “interest in culture shows itself in practice. How did a magazine that features Amaro de Freitas on the cover move away from cultural journalism, or how is it outdated?”

Regarding Pernambuco's design, he said that the criticism is “a matter of opinion. Others may have the opposite view. No one can say that a magazine is less interesting than a newspaper in terms of graphic possibilities. The previous project had not evolved at all since 2007. It spoke to a niche in difficult language. The niche may not be happy, but our effort is to speak to a much wider audience.”

The tension between academia and journalism is a long-standing cause for concern. Journalist Homero Fonseca, who worked at Continente from 2001 to 2009, five years as an editor, said that at the time he only had journalists and academics as collaborators. This division led him to create “the most concise writing manual known: ‘1 – Journalists: write like academics. 2 – Academics: write like journalists’. It was a unique experience,” he told LJR.

In this regard, Gomes said that he seeks “journalists and academics who do not write like academics. If I edit a magazine for academics, that's one thing. But, if I edit for the entire public, the magazine cannot be dull,” he said.

Researcher Natalia Francis, who studied contemporary Brazilian criticism in digital environments during her doctorate, highlighted the importance of the online presence of the media outlets, which do not yet have new websites up and running.

“For these media outlets, the internet does not serve as a dissemination platform, it serves as a means of maintaining contact with the public. There is no point in having a separation, there is an interpolation of media. These publications currently operate on the logic of creating a circuit,” Francis told LJR.

Still taking the first steps in their new iterations, the two magazines also serve to reflect on the usefulness of public support for cultural journalism in Brazil. The only existing similar initiative identified in Brazil is Correio das Artes, published by the newspaper A União in the state of Paraíba.

Gomes said that the longevity of the publications he edits was only possible because Cepe, the company responsible for the publication, “knew how to reinvent itself.” In addition to journalism, the publisher's investments in literature also bore fruit. In 2020, a book from the publisher won the Jabuti, Brazil's main fiction award.

“Any government could put an end to these magazines with the stroke of a pen, but that didn’t happen. There was a State commitment throughout several governments, and this happened because the official press knew how to reinvent itself and show that it was important for the population,” Gomes said.

One question that remains is about the possible influence of politicians on the magazine. In this regard, Fonseca says that I don't remember “any official pressure,” having gone through “the entire mandate of governor Jarbas Vasconcelos and two more years of the following administration, Eduardo Campos (from another political party)."

Cesar Maia has a different view, and said that “lobbying happened with some frequency. The bosses' task was fundamentally to try to protect the magazine's content from interference from people outside cultural journalism, linked to politicians, people who are no less relevant but are friends of the deputy or governor and are publishing a book. This shielding depended fundamentally on the editors-in-chief’s ability to say ‘this isn’t happening, we have autonomy.’”

Gomes ruled out this possibility, and stated that the time is one of independence and pluralism.

“There is zero political influence, there is none. I didn't receive any phone calls, not even the slightest hint. I don’t know if it happened in the past, but there isn’t one at present,” he said. “The objective is total plurality. This is one of the hardest things in journalism. It is much easier to say that you want to give a broad vision than to actually practice it.”