This is part two of an article addressing racism and the coverage of racial violence in Latin American newsrooms. To read part one, click here.

Recent coverage of racism and racial violence in Latin America has drawn attention to not only the need for this coverage, but the need to have more Black and Indigenous journalists in newsrooms. Some digital alternative magazines have questioned and analyzed issues of racism differently from many traditional news organizations -- and there are lessons to be learned from their coverage.

Betting on conversation

Kaja Negra is a digital media outlet based in Mexico. Most of its journalistic work has "to do with women from different fields and contexts and with LGBTQ people," journalist and coordinator Lizbeth Hernández told LJR in July. The site, she said, is a cultural project that integrates journalism, a publishing house, and an area of learning and imagination in the form of workshops.

When deciding how the outlet was going to contribute and how it was going to participate in the conversations that were taking place about racism since George Floyd’s murder in the U.S., Hernández said they decided to bet “on conversation, on listening” -- something she considers important in journalism.

Journalist and coordinator Lizbeth Hernández of Kaja Negra. Courtesy

"We believe that journalism is not just those great transnational and collaborative specials," Hernández said. "We can continue doing them, but listening, conversation, dialogue are also important to us, especially when we live in a country like Mexico that is so polarized."

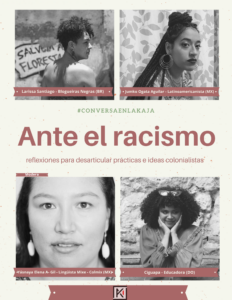

In June, Kaja Negra produced a YouTube live panel “Ante el racismo, reflexiones para desarticular prácticas e ideas colonialistas” (Facing racism, reflections to dismantle colonialist practices and ideas), and then in July had a YouTube live session with Jumko Ogata Aguilar, an Afro-Japanese and chicana writer from Veracruz, in which people were invited to ask questions, publicly or anonymously, about racism. In September, the site had another panel entitled "Ante el racismo: Reflexiones e ideas para desarticularlo” (Facing Racism: Reflections and Ideas to Dismantle It).

Hernández said Kaja Negra seeks to collaborate and experiment with different formats that encourage the participation of a person who may not be interested in reading a long text, but who would listen to, or ask a question during the live video session.

"We seek to create other dynamics, because although journalistic stories contribute a lot, we believe that there is also a time when we have to explore other ways so that people will become interested in the issues,” she said.

It is important to recognize and not make invisible, Hernández stressed, the work of groups that have already addressed the issue of racism long before it exploded in Mexican media. The more media outlets that question and analyze the issue, the more relevant and enriching discussions will be, she added. However, these conversations are being carried out mainly by collectives, civil associations and non-governmental organizations.

"That is where media must really put in the work because there are things that are much more interesting and are being discussed in a better way in other spaces that are not journalistic," she said.

Having these conversations in the newsrooms of the largest media is difficult, she explained, especially during a pandemic in which some mass media did not provide the work and health equipment, and in many cases, the necessary medical insurance for journalists to work safely. In addition, she emphasized that in order to really see inequality and discrimination in media it is necessary to analyze who those in positions of power and leadership are, to which families they belong and their skin color.

"When the media outlet or the project is questioning and analyzing [these issues], it will be noticeable in their work more than in their discourse, because one can make a tremendous speech and when it comes down to it, they come to you with the same formulas that are already proven," Hernández said. “For us it is that we do not want to recreate formulas that have been done before. We want to question and analyze, to address it.”

It is not enough to talk about racism, there must be anti-racist journalism

Writers at the digital magazine Afroféminas, which has collaborators from across Latin America, Puerto Rico and Spain, have helped to make the forced disappearances and crimes committed against Black people in the region visible. Such is the case with the article, “El racismo no acaba, la guerra no termina y ¿A quién le importa las vidas negras en Colombia?” (Racism does not end, the war does not end, and who cares about the Black lives in Colombia?), which talked about the massacres of Black youth and adolescents in just one week of August this year in that country.

"[Five] Afro-descendant boys were murdered in Cali and many people in Colombia did not associate [that] as a hate crime, as it was with the crime of George Floyd in the United States," Alejandra Pretel, Afro-Colombian writer and the site’s representative in Argentina, told LJR. It should be noted that Floyd's murder was recorded and had massive worldwide coverage, she said, but this presents another problem. "[We must] think about what level we have reached that the only thing that sensitizes me is seeing a person dying to understand that a structural system exists and that there are people who are violated every day by those systems."

Alejandra Pretel, Afro-Colombian writer and Afroféminas’ representative in Argentina. Courtesy

Floyd's case was on the front page of many media, something that does not usually happen with racialized people in media in their own countries, Pretel stressed. "It is also important to think about that, that we are in a globalized world and that what happens in the United States is on televisions everywhere and what happens in Latin America, quite honestly, hopefully we will find out," she said.

But, in addition to disseminating these cases, Pretel added that it is important for media to exercise anti-racist journalism, which is more proactive and requires internal questioning by the journalist and the team.

In Colombia, Pretel explained, the ideology of trietnia is deeply rooted, that is, everyone has something Indigenous, Black and white, but the purpose is to whiten both people and customs.

"When I write an article and talk about the Colombian context, I put white people and mestizo people in the same category because due to a lot of historical and social dynamics, mestizo people in Colombia are people who are ethnically privileged," she said.

Anti-racist journalism, Pretel explained, requires unlearning many issues that propagate stereotypes and discrimination, and this includes the language used in the newsroom. In July, Agrupación Xangô, an organization led by Black activists with a social justice approach, and which Pretel is also part of, denounced via Facebook an article from Argentina’s newspaper Clarín. The headline read that Venezuela is “Africanized” and had a photo that showed a Black man eating from the trash. The group declared that the headline was racist and “linked Africa with poverty, marginalization, vulnerability. Pure racism.”

Pretel reiterated that it is necessary to review language, images and concepts that are used and their origins. She gave as examples the etymology of the word denigrar, which is "to make more black," and the word quilombo, which in Argentina is used to mean disorder, when in fact they were spaces where Black people escaped from slavery. She also added that it is necessary to integrate Indigenous people and Black people into the news team.

"An anti-racist journalism goes beyond showing the violence suffered by racialized people, but rather to stop using stereotypes, stigmas, racist language in what we write or what we could create from that place.”