In the last two years, the migration of Cubans to the United States has shot up exponentially as a result of factors such as the economic crisis unleashed after the impact of COVID-19 on the island and after monetary reforms approved by the regime at the beginning of 2021.

The above, coupled with changes in U.S. immigration policies, has led to an exodus at record levels between 2021 and 2022, a period in which more than 220,000 Cubans arrived at U.S. land border points, and more than 3,000 entered by sea, after crossing the Florida Straits.

While the figures show that most of those who leave Cuba for the United States succeed in their journey, there are some who die or disappear along the way.

Faced with such a migratory emergency, DeFacto, the fact-checking and data journalism unit of the independent Cuban digital news outlet elTOQUE, wanted to focus precisely on the dead and missing migrants, of whom little is said in the press and whose stories fade out among statistics.

elTOQUE's multimedia and data journalism project seeks to compile the identities and stories of Cuban migrants who have not made it to the U.S. (Photo: Screenshot of elTOQUE)

The result was "Migrar: Una decisión de vida y muerte [Migrating: A life and death decision]," a multimedia and data journalism special that seeks to compile the identities and stories of Cuban migrants who did not make it to the United States, while offering a service of accompaniment and information for the families of the missing and a tribute to those who lost their lives.

"There is drama behind this, there are not only happy stories, there are also people who have not made it and that is what we wanted to tell," Jessica Domínguez, editorial coordinator of the project and director of DeFacto, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “No matter how small the numbers [of migrants who don't make it to the United States] are, we need to count them, we need to know how many there are, where they are, who are the people who haven't made it. That was the essential motivation to start with this product and no other. We tried to go after the data and information that was missing.”

"Migrating: A life and death decision" consists of a database on people who have died and disappeared during their migratory journey, obtained from sources such as press articles, official reports and social media posts. The database is organized by migration events (deportation, detention, death, disappearance, or rescue), type of migration (land or sea), place (country, city and geolocation), number of people involved, among others.

The database, which has open access and is downloadable, was developed after more than a year of monitoring the various sources to gather enough information to reflect an overall picture of the situation. However, the database continues to grow as the project progresses.

"This special is not the end of the journalistic work, but rather the starting point. It is a living work," Domínguez said. "The process of identifying people has been very difficult because the information is absolutely scattered, dispersed. [...] What we did was to start building a database where we systematized all the events associated with Cuban migration that we were detecting in a series of official and media sources that dealt with the issues. From there, we started to cross-reference."

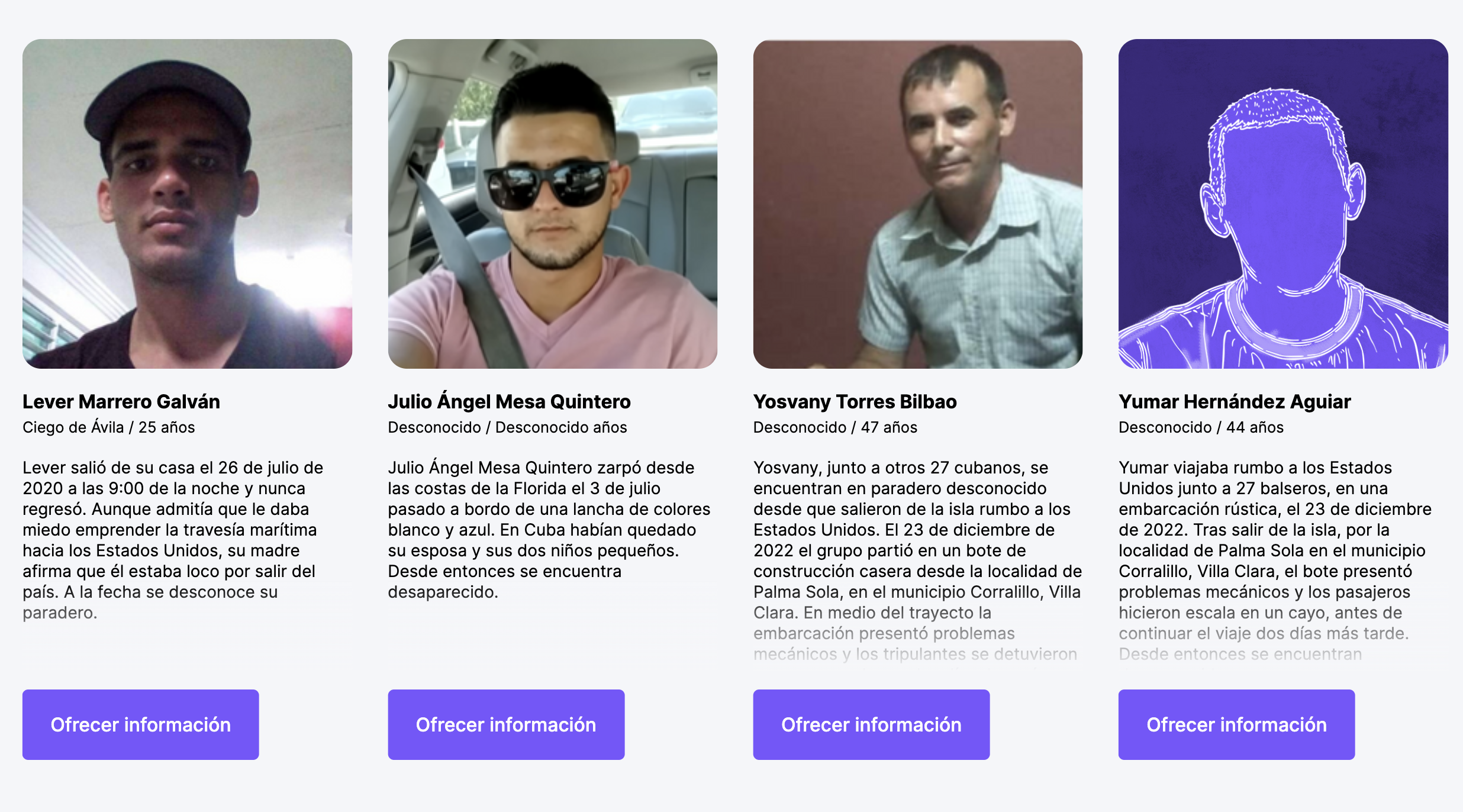

From the database, the DeFacto team developed a section with profiles of the more than 118 deceased persons they have been able to identify as of March 25, 2023. The profiles include name, age, photograph, and circumstances of death of the deceased.

They also developed a section with the profiles of missing migrants, which as of March 25 totaled 357. The purpose of this section is to help families find the whereabouts of their missing persons. To do so, the digital news outlet resorted to a crowdsourcing process through an open form, with which readers are invited to contribute with data to complete the information on the missing that could help to find their whereabouts.

"When someone disappears, they can remain in that state for months and the family knows absolutely nothing. So we want to help at least to shed light, to publish that information, to try to facilitate contacts, to facilitate information as much as we can. Because we also understand that we are not a migratory authority and cannot give exact answers, but we can help with information," Domínguez said.

Since the special’s publication on Feb. 27, DeFacto has increased the number of cases of missing or dead migrants thanks to information provided by relatives, which the team verified with Cuban institutions and organizations that also monitor migrants. From 91 deceased people reported at the time of publication, the number increased to 118 less than a month later.

But the crowdsourcing process is not limited to the open form. The team has a proactive role that involves an entire community management strategy. This includes what the team calls "active outreach," which consists of searching social networks for relatives of deceased or missing migrants in order to obtain information that will help them fill gaps in the database.

Readers can contribute with information that could help find the missing migrants through an open form. (Photo: Screenshot from elTOQUE)

"We have collected a lot of data, but there are many people who are incognito, we don't know who they are," Loraine Morales Pino, who is in charge of the project's community management, told LJR, "[We] try to find out what part of the island they come from, so we take on the task of — based on the relatives' own reports or by gathering information from relatives — them giving us the information."

Facebook and Facebook Messenger are the platforms that have been most useful to the DeFacto team to get in touch with migrants' relatives, explained Morales, who personally talks to people and manages the information. Once communication is established, the journalist asks relatives if they wish to move to other platforms for a more secure interaction, such as WhatsApp.

Since the special was published, Morales has contacted at least 50 families. In the process, the journalist and her team have encountered people who are open to providing information, but also people who are suspicious and hesitant to provide sensitive information about their relatives.

"There is this feeling of persecution. The family is sometimes a bit fearful, because at the same time there have been cases of extortion, mainly from groups that live, for example, in Mexico, who call them and tell them that their family member has been kidnapped," Morales said. "That’s where we also put into action a mechanism of delicacy, of putting oneself in their place. I tell them 'this is my Facebook profile, I am the information manager. If you like, we can have a video call and you can verify that I am who I say I am.'"

Morales added that, so far, no person she has contacted has refused to collaborate. However, there are also people who not only agree to provide information without hesitation, but also ask the team to help them locate their migrant relatives.

"I feel that there is a kind of lack of political will to help these relatives by governmental or diplomatic institutions. The families feel very lonely, that is what I’ve been able to perceive," Morales said. “I always tell family members that we have every disposition [to help] and that we are totally sensitive to their situation, although we cannot fully understand how difficult it must be for them. But we do want to accompany them, precisely so that they feel that their pain matters.”

After talking to relatives, the team cross-checks the information with existing records and uploads it into the database. A few days later, they contact the families again to follow up and find out if there is any new information.

In the next stage of the project, DeFacto will seek to establish pathways to act as intermediaries between the families of migrants and authorities in the various countries where migrants die or disappear. Morales, who lives and works in Mexico, has begun to investigate what would be the ideal management channels to more effectively reach out to agencies that could help Cuban families.

"In the case of Mexico, there are many collectives here devoted to searching for missing persons or missing migrants. These are experiences we can draw on [...] to move forward a bit faster," Morales said. "We want to forge these links or these collaborations with civil society organizations that, at the same time, have already traveled this road, to give us tips or show us ways to reach authorities in perhaps a more effective way."

Morales said that in April they will undertake the task of contrasting the database of "Migrating: A life and death decision" with the records of authorities not only in the United States and Mexico, but also in the Bahamas, where hundreds of Cubans have arrived in their attempt to reach the Florida Keys.

When it comes to obtaining official figures on any subject, Cuban journalists always run up against the secrecy that characterizes Cuban authorities, who rarely make public information about their actions.

And migration is no exception. For the production of the multimedia special, the DeFacto team has had to resort to official data from other countries and information from independent Cuban media operating from outside the island.

"From Cuba there is nothing. Everything we have looked for has not been from Cuban sources. Cuba does not give away those statistics. We don't even know, for example, how many people have left legally, because a lot of this migration leaves legally but continues illegally in the rest of the borders," Domínguez explained. "The rest of the sources [we have consulted] have been in Mexico, in the United States, in the Bahamas, in Nicaragua, and in other regions."

Since the publication of the project, the DeFacto team has been able to identify almost 120 deceased migrants. (Photo: Screenshot from elTOQUE)

However, the biggest challenge for the team behind "Migrating: A life and death decsion" has not been access to information, but the correct handling of it. The creators of the multimedia special are aware that they are working with a very sensitive subject that affects thousands of Cubans. Nevertheless, DeFacto decided to do it in order to leave a graphic testimony of the consequences of migration and to put numbers and faces to the phenomenon.

"We know that it is a painful subject that is also alive, in full development and has not ended, so we are telling practically in real time painful situations for the families," Domínguez said. "Managing that for us is an important challenge. There is a level of specialization or a level of sensitivity that makes journalists who work with these issues different from those who work with other types of material."

A month after its publication, the special has had an impact inside and outside the island. It has been picked up by media outlets such as Telemundo, in Florida, and the independent news outlets Incubadora (Cuba) and Descifrado (Venezuela).

In addition to the databases and profiles of migrants, the special has spinned off a dozen stories on the migratory phenomenon, as well as videos for elTOQUE's YouTube channel and its social media.

"For us, the impact on the Cuban community is relevant as well. [The special] has opened the door to a social debate in multiple media on this issue," Domínguez said. "It has triggered being able to speak forcefully about figures, data, but above all about people's names, to put a face to a phenomenon that touches many families."

Banner photo: DukeUnivLibraries via Creative Commons