On Sept. 21, 1973, ten days after the coup d'état led by General Augusto Pinochet against the democratic government of Salvador Allende, one of the most important photojournalists active during [a then prevailing] military dictatorship in Brazil arrived in the Chilean capital. Evandro Teixeira was sent to Santiago by Jornal do Brasil, where he worked, with the goal of documenting the establishment of a new dictatorial regime in South America. During his brief stay, of little more than a week, he registered notable facts such as the burial of poet Pablo Neruda, prisoner conditions in the National Stadium, and the ostensive presence of tanks and soldiers in the streets of Santiago.

One hundred and sixty of these photographic records, most of them unpublished, make up the exhibition “Evandro Teixeira, Chile, 1973.” It will be displayed from March 21st through July 30th at Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo, Brazil, curated by Sergio Burgi. The exhibition takes place months before the 50th anniversary of the coup in Chile, and has renewed relevance in a moment in which Brazil has just had, for the first time since the re-democratization in 1985, a government led by a former military man with antidemocratic tendencies. The exhibition also highlights the importance of photojournalism for historical documentation, and shows the power of a photographer's courage and tenacity when backed by a strong, well-structured newspaper.

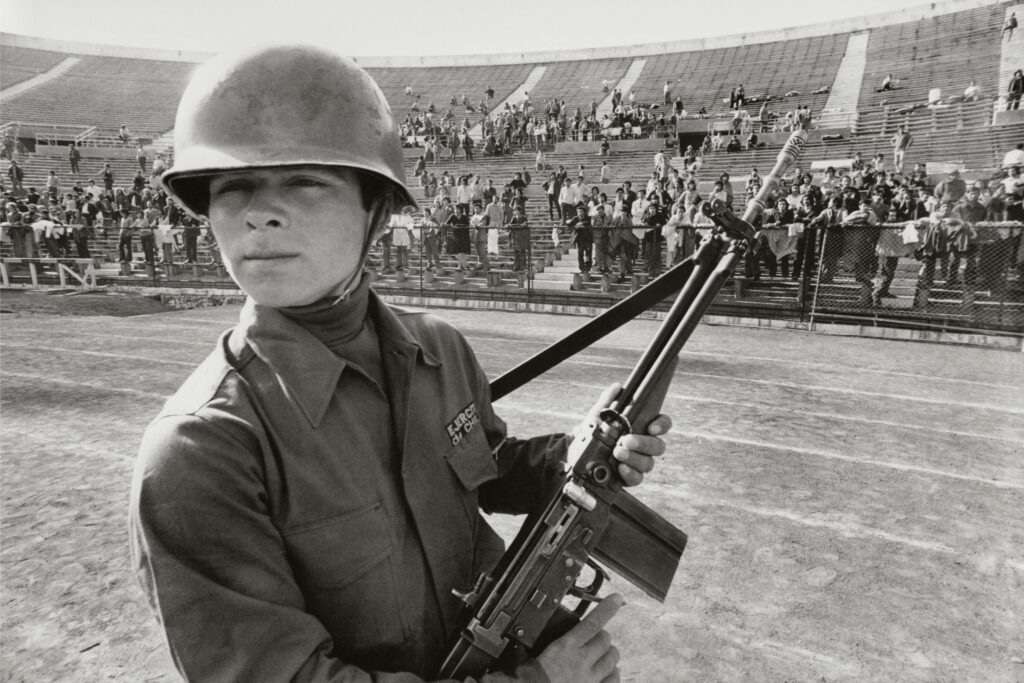

Armed soldier in front of political prisoners in the National Stadium in Chile 09/22/1973 (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection)

Portrait of Evandro Teixeira in Rio de Janeiro in 2013 (Photo: André Arruda)

Teixeira traveled to Santiago with reporter Paulo Cesar de Araújo on Sept. 12, the day after Allende's overthrow and suicide. However, the military junta that had taken power in Chile closed the border and the pair had to spend nine days waiting for it to reopen in Mendoza, on the Argentinean side of the Andes, before finally being able to travel by bus.

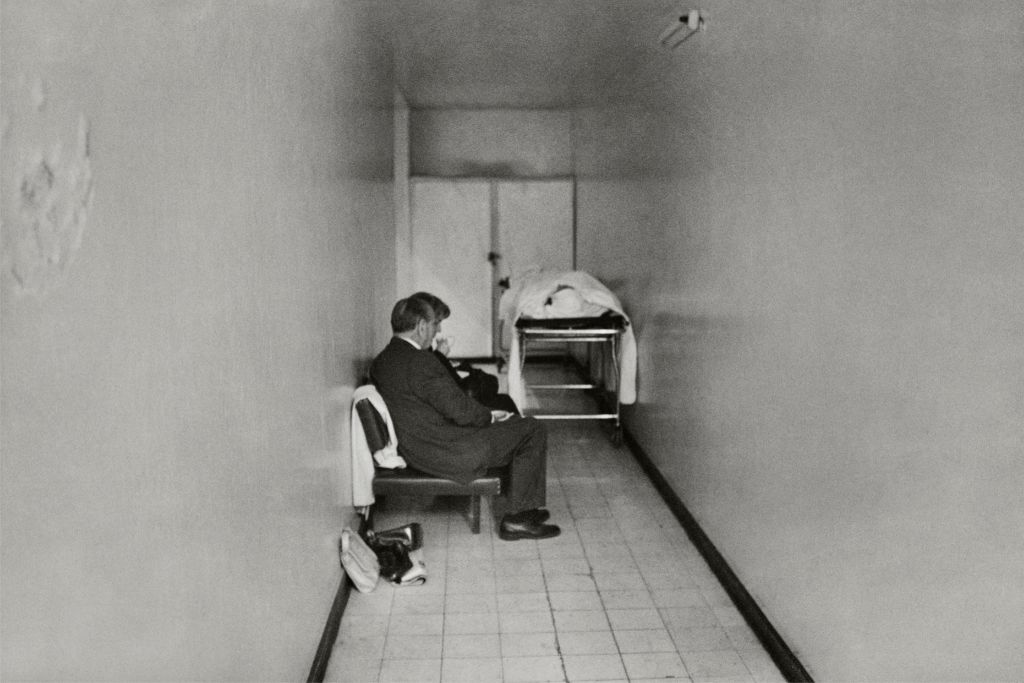

Two days after arriving in the Chilean capital, Teixeira learned from the wife of a diplomat that Neruda, then Chile's greatest poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature less than two years earlier, had been hospitalized. The photographer went to the clinic, but did not photograph the writer, who died that same night. The next morning, already aware of his death, Teixeira returned to the hospital, and wandered around the surroundings.

"Suddenly, a door opened on the side of the building and I went in, with a camera in my pocket," Teixeira, 87, told Latam Journalism Review (LRJ) in his apartment in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. "I was lucky. What helped me most in my career was luck, besides the will to do the job. I always believed I would be able to make the agenda work, and I never had any respect for the acts of madness of those in charge."

Body of the poet Pablo Neruda at Clínica Santa Maria, guarded by his widow Matilde Urrutia, in Santiago, Chile, 09/24/1973 (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection)

Inside the hospital, Teixeira found Neruda's body on a stretcher, watched over by his widow, Matilde Urrutia. The photographer told her that he had photographed the poet five years earlier in Brazil, at a meeting with Brazilian writer Jorge Amado. "She told me, 'your presence is very important here.’ But it wasn't me who was important, it was this beast here, who has impressive power," Teixeira said, picking up from his office desk a Lumix LX100 digital camera, fitted with a Leica lens, the brand he has always used.

The Brazilian photographer was the only one to capture Neruda's body in the hospital, a photo he considers one of the most important ones in his career. Doña Matilde, as she became known, not only authorized him to document the body, but asked Teixeira to accompany her to the couple's residence, La Chascona, where the wake would take place. "We knew he had been murdered by that scoundrel Pinochet," Teixeira said, using an expletive he employed every time he referred to the former Chilean dictator. Lab tests made on the poet's remains released in February concluded that Neruda was poisoned, confirming decades-old suspicions.

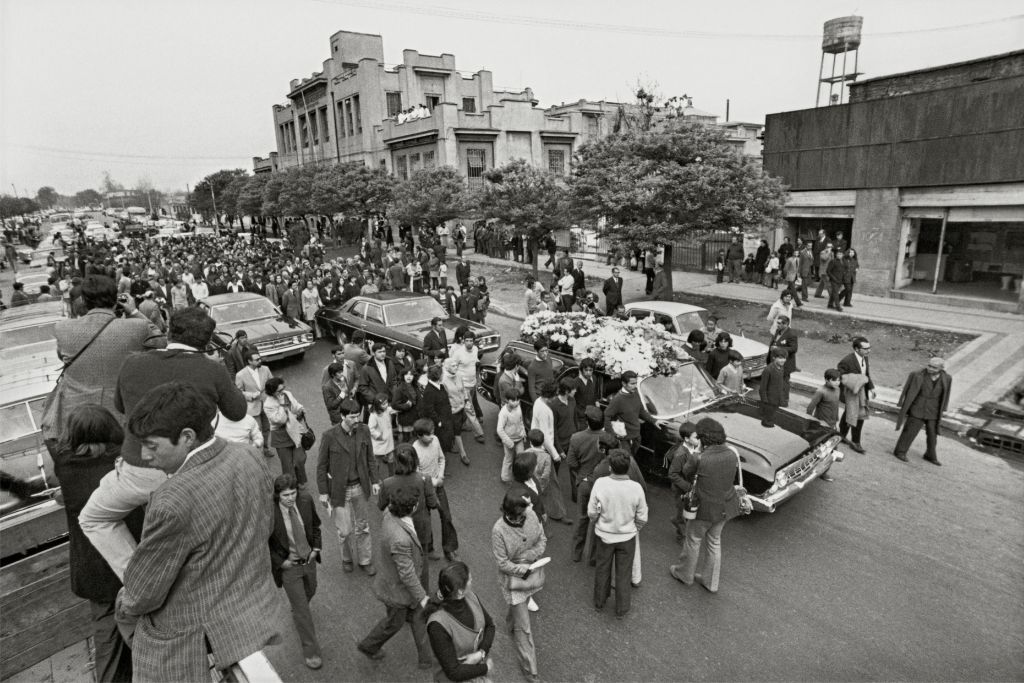

All stages of the poet's wake and burial, which had a large popular turnout, were photographed. The photos show the event gradually filling up, after starting with just a few people. The wake became the first major act against the new dictatorship. Aware of the popular support, Pinochet scheduled a speech at the same time, which Teixeira ignored in order to remain at the funeral.

For curator Burgi, the presence of the international press at the poet’s farewell prevented possible Army repression during the procession through the streets. "Even fascists have to be accountable to international public opinion, and this is a lesson not to be forgotten," he told LJR.

On the way to the General Cemetery of Santiago, the crowd grows with popular supporters, supporters and militants of the Popular Union parties, the coalition of parties that elected Salvador Allende in 1970, on 09/25/1973 (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection )

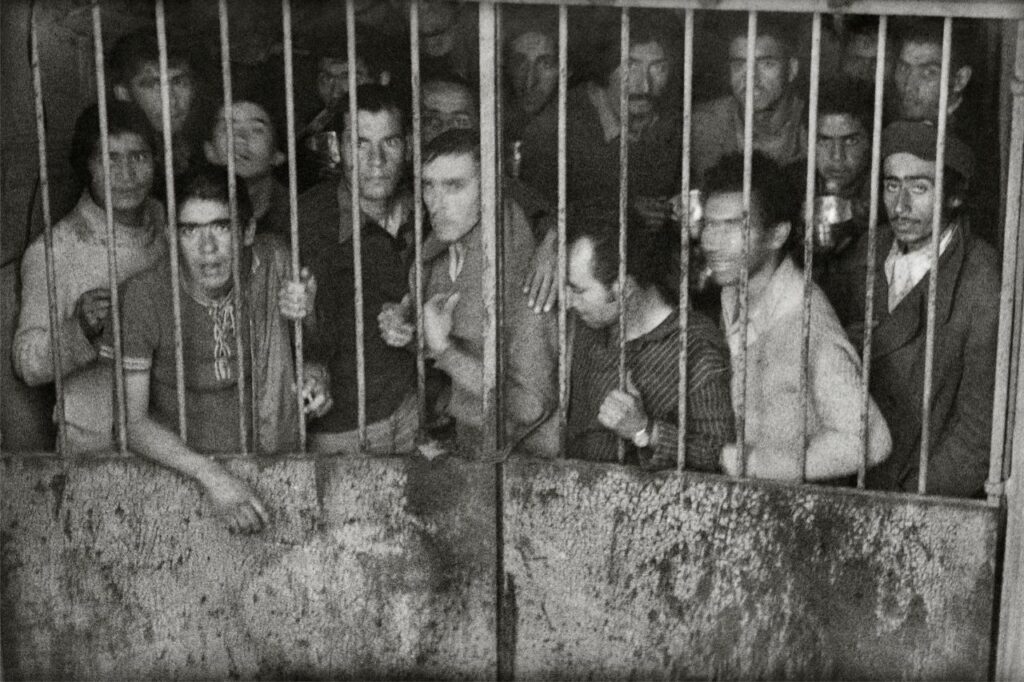

The images that Teixeira took at the National Stadium in Chile, a detention and torture center for thousands of political prisoners, are another core part of the exhibition. At the time, international correspondents were taken by the military themselves to photograph the space, in an official initiative that aimed to cover up the human rights violations that took place there. The military intended to show only a small number of detainees, those under better conditions, in order to deny the occurrence of abuses.

Teixeira had been in the stadium before, during the 1962 World Cup. Along with colleagues, he escaped the official tour and was able to document the unplanned arrival of trucks with a large number of new political prisoners at the stadium. In addition, he managed to enter the basement of the venue, where young students were clustered in overcrowded cells.

"At that moment, the whole visual narrative planned by the military broke down. These photos create a total deconstruction of the official account expected by the regime," Burgi said.

Political prisoners imprisoned in the basement of the National Stadium, Santiago, Chile, 09/22/1973. (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/ IMS Collection)

Two of the photos were published by Jornal do Brasil on Sept. 25. At the time, censors of the Brazilian regime worked in the newsroom deciding what could or could not be published. "I wouldn't be surprised if, during conversations between editors and censors, the argument to get around the censorship was that it was an official visit to the stadium, organized by the Military Junta," the curator added.

Teixeira corroborated this thesis. "Photography always managed to get things past the censors that reporters themselves could not. Censors had more difficulty understanding images," the photographer said.

Many other photos show a heavy military apparatus in the streets of Santiago, where a curfew was then in effect. There are also images of the De La Moneda Palace destroyed by bombs dropped from airplanes. In addition to circumventing local repression, Teixeira needed to develop the images quickly in a small improvised photo lab, which he installed in his hotel room bathroom, and then transmitted them to Rio de Janeiro, where the Jornal do Brasil newsroom was located, using a wirephoto device.

In addition to the photos in Chile, the exhibition includes 30 photographic records of the Brazilian dictatorship. These show from the seizure of power by use of force, in 1964, to the growth of popular demonstrations against the regime from 1968 on, in a dialogue between the two countries. Aside from books and other objects, such as cameras and press badges, the exhibition also presents two films that document the period, Septiembre chileno [Chilean September], by Bruno Moet, and Brasil, relato de uma tortura [Brazil, report of a torture case], by Haskell Wexler and Saul Landa.

The exhibition also prompts a reflection on the importance of the press in authoritarian contexts. Under editor-in-chief Alberto Dines, Jornal do Brasil was the main voice among the major Brazilian publications to denounce the arbitrary actions and violence committed by the military regime. According to Teixeira, the former editor, who died in 2018, "broke the news. He was not intimidated. And he was willing to talk to journalists and photographers, he was very open.

Cover of Jornal do Brasil on September 12, 1973, the day after the coup d'état in Chile, with no headline or photo to circumvent censorship (Image: Jornal do Brasil Reproduction )

The cover published by the newspaper the day after the Chilean coup is historical: Brazilian censorship had authorized that the fall of Allende be reported, as long as there were no headlines or photos on the front page. Jornal do Brasil then made a cover without any headlines or pictures, whose only news, printed in large letters, was the Chilean coup. Outside the visual standards of the newspaper, but respecting the censorship order, the page drew more attention than if it had followed the ordinary.

In addition, the newspaper had undergone a major graphic changes in the late 1950s, which, among other elements, gave prominence to photography on its cover and in its sections. According to Teixeira, in the 1970s there were 35 staff photographers, a number considered high for the current average of a large Brazilian newsroom.

"The newspaper had power. We could travel wherever we wanted," the photographer said. "Nowadays, they would probably use photos from news agencies. But it's different when the newspaper uses its own professionals, who know the house look."

After decades of crisis, especially in the last 12 years, Jornal do Brasil closed its print edition in 2010, practically ceasing to produce original content. After 47 years at the publication, Teixeira resigned three days before the official announcement of the newspaper's end. In 2018, there was an attempt to bring back the print edition, but it lasted just over a year. Journalists from this latest incarnation are claiming in court the payment of back wages.

Teixeira, who is currently in poor health after two Covid-19 infections, but whose reasoning remains perfectly lucid and sharp, said he got part of his nearly five-decade collection from the newspaper, but not everything. What he did get, he gave in 2019 to the Moreira Salles Institute, which currently houses more than 30 archives of Brazilian photographers, making it available for research and to other institutions that want to promote exhibitions. Before this exhibition, among nearly 300 photos by Teixeira in Chile, only seven had been published.

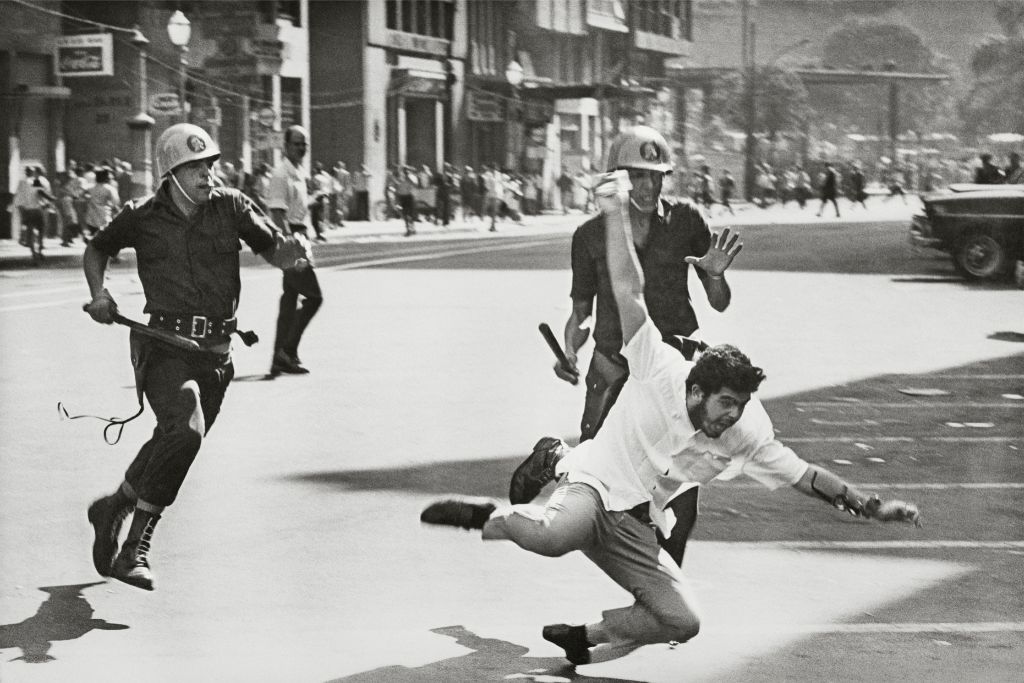

One of Evandro Teixeira's most famous photos, in which soldiers knock down a student running in protest in Rio de Janeiro on June 21, 1968 (Photo: Evandro Teixeira/IMS Collection)

Besides São Paulo, Burgi plans to take the exhibition to Chile, for the 50th anniversary of the coup, and at least to Rio de Janeiro. The curator understands that the exhibition allows new angles of perception regarding the present situation in Brazil, where, in his attempt for reelection last year, Jair Bolsonaro, public defender of the military dictatorship, got 58.2 million votes, equivalent to 49.10% of the electorate.

"The exhibition reveals the importance of documenting moments when there are unacceptable acts, when the Armed Forces of a country are used against its population," Burgi said. "Looking at the dictatorships in Chile and Brazil helps to understand how violent, regressive and discriminatory authoritarian processes are. The photographs help younger generations, who grew up in a more freer environment, to understand what it is like to have their viewpoints canceled out. These ruptures, with which we have recently flirted, represent decades-long setbacks."