This story was edited and changed for clarity.

The press in Nicaragua has faced attacks and obstacles such as the concentration of media and the lack of access to information since Daniel Ortega came to power. But after the protests of April 2018, when the police violently suppressed protests against the Ortega regime, the situation of freedom of expression worsened to levels that Nicaraguan journalists did not imagine.

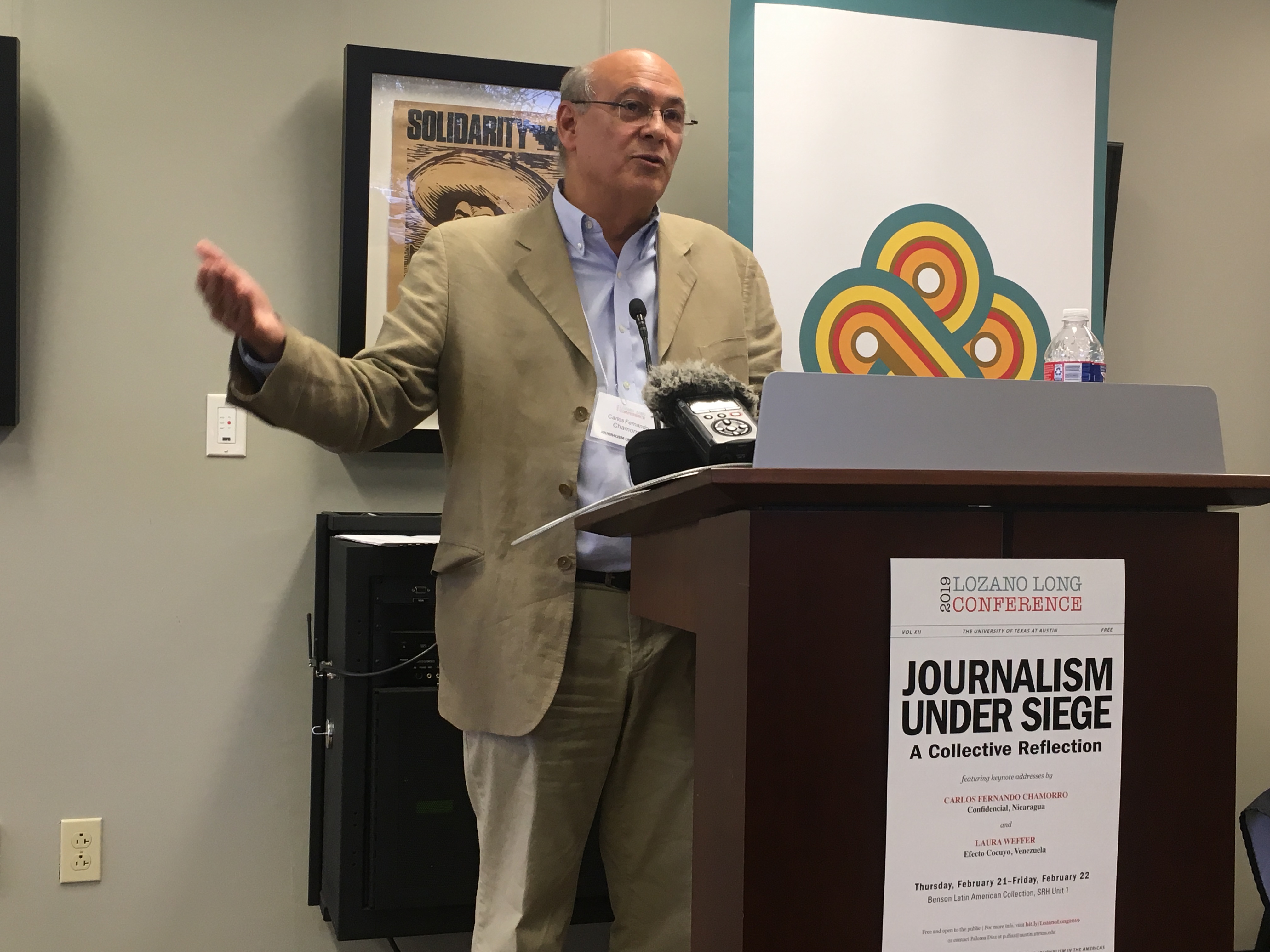

Carlos F. Chamorro directs the independent news site Confidencial from exile in Costa Rica. (César López Linares/Knight Center)

Carlos F. Chamorro directs the independent news site Confidencial from exile in Costa Rica. (César López Linares/Knight Center)For journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro, who left Nicaragua in January and is now working from exile in Costa Rica, getting used to working in conditions of physical and legal insecurity has been a challenge.

As a keynote speaker at the 2019 Lozano Long Conference "Journalism Under Siege," organized by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies and the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at the University of Texas at Austin, Chamorro said journalists attacked in Nicaragua have been at risk of crossing the thin line between journalism and activism.

"We were not prepared to work in conditions of insecurity as in other places. I believe that in El Salvador, in Mexico, in Guatemala, and in other places they went through this kind of crisis before. For us, adapting to that was a shock. And on the other hand I would say that also it has been difficult to manage that line of activism and to push the 'brake' and say 'here we are journalists and we have to put a limit and tell the story in this way.’ It is extremely difficult, because of passion,” said Chamorro, son of former president Violeta Barrios de Chamorro and Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, newspaper editor killed in 1978 during the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza Debayle.

On Dec. 14, 2018, the National Police raided the newsrooms of Confidencial, the weekly that Chamorro founded and directs to this day, and of the television programs “Esta Semana” and “Esta Noche.” A week later, there was an assault against the channel 100% Noticias and the detention of communicators such as Miguel Mora and Lucía Pineda, who have been in prison since Dec. 21, 2018. Chamorro learned that there were direct orders from the Ortega regime to criminalize the exercise of journalism and criminally accuse other journalists, and that led him to make the decision to go into exile in Costa Rica, where he has been since January of this year and from where he continues to remotely direct the newsroom of Confidencial and record his record "Esta Semana."

"The challenges are enormous because in my particular case half of my newsroom is in Managua under very precarious security conditions, and the other half is dispersed in four different countries," he said.

Within these circumstances, media have found important tools in social networks and mobile devices not only to do journalism from a distance, but to fight censorship.

"I didn’t fully value or appreciate the potential for communication that these devices have because the truth is that in Nicaragua they were used primarily for very frivolous, recreational things, of spectacles, of communication, of gossip. But at that time they became the main mechanisms to document repression and resistance,” Chamorro said. “Journalists in some ways became curators in that whole process."

For Chamorro, the difference between the current crisis of freedom of expression and that of previous years in Nicaragua is that before, even despite obstacles, journalists were able to denounce corruption and report on the acts of Ortega's regime, because the press was tolerated as long as it did not represent any risk for the dictatorship.

"The journalism that we did did not have direct consequences, first because all the agencies of the State, the justice, the parliament, the prosecutor's office are controlled by the Executive, nobody would do an investigation," Chamorro said.

"The regime could tolerate media that were obviously critical to the extent that its power was not being put at risk by any social and political movement. That changes after April 18," the journalist later said.

According to Chamorro, an example that journalism is beginning to have consequences in Nicaragua is the work of Confidencial journalist Wilfredo Miranda, "They shoot with precision: to kill!", which permitted a pattern of extrajudicial executions used by the police and paramilitaries during the protests of April 2018 to be established.

The report was recognized this year with the King of Spain Ibero-American Journalism Award and was cited profusely in the reports of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States (OAS) and by the Interdisciplanary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI) that investigated more than 100 murders that occurred in the first six weeks of the repression.

Chamorro said that despite the attacks against Confidencial, the news site has recorded a significant increase in audience, as has happened with other independent media. Chamorro attributes this rise to the fact that young people and people who previously did not consume information, began to do so, and also that the supporters of the Ortega regime do not have reliable channels to inform themselves, given the concentration of media in the hands of people close to the country’s leader.

"The system of official media, all those channels that they came to buy and to have, that dominated and presented the football games and that did the big events and the great shows, that attracted the youth, in a crisis like this, are useless, have zero credibility," he said.

The recent harassment against the press is partly a consequence of the media having increased the visibility of the protests and acts of repression, Chamorro added.

"There is a social, political rebellion, and under these circumstances it is intolerable that there are media that are catapulting and expanding the resonance that the protest has. There is also revenge and there also was a rupture in the system of control of media," so that now there are more journalists and independent media.

The situation in Nicaragua does not seem to show signs of improving, however Chamorro has reason to believe that the regime is unsustainable. And, from exile, he has faith that journalism will resist to be able to witness a democratic change in that country.

"We believe – at least I believe and I want to have the conviction – that we are going to be able to tell the story of how this dictatorship is changed in a peaceful way," he concluded.