Faced with both physical and digital threats to the safety of journalists in Mexico, a group of leaders from civil society, media, technology companies, academia and the government met recently to discuss how to sustain journalism in a country that has seen 144 deaths of journalists and media workers from 2000 to date.

“The safety and security of journalists is under threat globally, but with greater intensity in certain parts of the world. Mexico is one of those places,” reads a report prepared in the wake of the event.

Participants of the private meeting discussed not only the physical and digital threats to journalists in Mexico, but also ways technology can help protect them. They also looked at the impact of government policies on the industry.

Among the recommendations? More collaborative projects, building alliances, improving media and digital literacy and paying greater attention to cybersecurity. They also said there must be more global pressure and public support for journalism, as well as further development of technological tools.

Battling different types of violence

“Sustaining Journalism in the Face of Security Threats” was held on June 25, 2024 in Mexico City and convened and co-sponsored by the Center for News, Technology & Innovation (CNTI), and news company Mexican Editorial Organization (OEM).

(Raquel Abe/Knight Center)

The meeting was part of CNTI’s plans for cross-industry meetings that promote evidence-based, reflective conversations with the goal of building trust and ongoing relationships.

One of CNTI's main goals is to analyze what is happening with journalists' cybersecurity and online harms and abuse that journalists are experiencing, said the organization’s executive director Amy Mitchell.

“Mexico in general is one of the most dangerous places for journalists, particularly around these two topic areas, (cybersecurity and online harms and abuse), so it makes a lot of sense to host this convening in Mexico City,” Mitchell told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

And although the original plan was to focus more on digital security, participants expressed that it was necessary to also talk about the physical threats that journalists face in Mexico, Martha Ramos, editorial director at OEM, told LJR.

According to a study by Reporters Without Borders, Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries to be a journalist. And more than 40% of the attacks, both physical and digital, that have been documented in Mexico were linked to government actors, according to an Article 19 report.

The more than 20 participants in the meeting delved into the different types of violence that journalists experience in Mexico, including online harassment, defamation, spying and threats. The people carrying out these attacks include not only organized crime, but also authorities, civil movements and citizens.

“CNTI was very struck by the penetration of violence in all areas due to the growth of organized crime, because they did not know it in depth. That is, how the growth of the cartel organization itself has penetrated levels of government of various ranks,” Ramos said.

“It is always striking how it has permeated so much that covering a crash in the street can be something that costs you your life, because it turns out that the person in the crash was someone you shouldn’t photograph,” she added.

Unfortunately, violence against journalists has permeated much more in the most marginalized areas of Mexico, largely due to the absence of professional journalism and organized media companies that can protect their journalists, Ramos said.

“There is an absence of state protection, and there is a need to communicate. This need to communicate leads people to create Facebook pages, to denounce things through social networks, they do not have a formal media outlet, they do not have the training, and this ends up putting them at a very high level of risk,” Ramos said.

The nature of this violence varies according to the different ways in which journalists carry out their work in Mexico, according to the report.

“In some regions and localities, journalists handwrite their stories which are then delivered within local communities, increasing the risk of encountering physical threats and violence,” the report said.

(Raquel Abe/Knight Center)

Threats are also finding journalists online. For example, the report noted a major leak in journalists’ personal data in January 2024, or highly sophisticated cyber threats attacking journalists.

Another problem is coming from the journalists’ phones themselves.

“One of the things we heard in Mexico City’s convening, as well as elsewhere, is in many cases journalists are working on devices that are four generations old, they are personal devices. How can technology build stronger tools that really facilitate the needs at the time,” Mitchell said.

Armando Talamantes, executive director of Quinto Elemento and one of the meeting participants, told LJR that the situation of the press in Mexico is precarious.

“We now live in a context where the host of the most popular radio news show can be the target of an armed attack in Mexico City or a female reporter can be harassed for days on social media just because she asked the president an incisive question,” he said.

Recommendations for moving forward

Despite the adverse conditions that journalists in Mexico face in terms of physical and digital security, the meeting participants identified practical steps to reduce the damage. Although they are aimed at journalists in Mexico, they are applicable throughout the world, according to the report.

The first recommendation concerned digital and cybersecurity literacy.

“This kind of knowledge requires journalists and their employers to dedicate themselves to new training that builds ongoing knowledge of and comfort with technology, the ways to use it for their protection and the ways current practices and programs can compromise it,” the report said.

The participants also recommended further development of technological tools and use of artificial intelligence. The goal is to build stronger and more comprehensive technological tools to combat online attacks.

“Such tools, along with greater digital literacy, can help the benefits of technology outweigh the harms,” the report said.

The participants also discussed exploring regulatory options, which is especially difficult because government leaders in the country are often at the head of attacks on journalists.

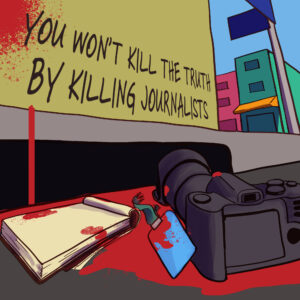

A 2010 protest in Mexico City against the murders of journalists (Knight Foundation, CC BY-SA 2.0)

“This makes regulation a challenging strategy. Regulation could not only fall short of its intended goal but also backfire,” the report said.

Some participants shared that they have been working toward legislative protections for decades but without any improvement in the safety of journalists in Mexico.

And finally, participants mentioned that the State must take a role in protecting journalists, and emphasized that the global community should pressure States to do so.

The global community also has a role to play in taking cases of abuse to court to set legal precedent. And the global community can create safe spaces for knowledge and lesson exchange.

Finally, the participants said media must build trust with the public so that citizens will support journalism, and to nurture young journalists who will want to enter the profession.

Next steps

Following the publication of the post-meeting report, Ramos said next steps should be to create a communication network with the participants to carry out projects with a common goal that also address the problems discussed. She hopes that this effort will come to fruition before the end of the year. In order for that to happen, efforts must be made to insist on collaboration and unity from the Mexican journalism industry.

Mitchell said CNTI will continue to share the findings and recommended steps arising from the meeting in Mexico. Another plan is to launch an international survey for journalists at the end of September. It’s based partly on the experience in Mexico and is being drafted now.

“It will be translated in at least nine languages. It has the potential to reach a nice group of journalists globally,” she said. “That will be a terrific way to gather more data about what they are experiencing, if they have avenues to talk about it, to share information, if not, what are the mechanisms to facilitate that.”

Additionally, CNTI is reviewing the possibility of creating a “living database” for journalists, which is safe and secure, where they can share what they are experiencing and connect with other colleagues experiencing similar issues in other parts of the world, Mitchell said. Having a database that is continually collecting information makes it easier for technology companies to have a better idea about what is happening, she added.

“This is not the first time an external organization is interested in what's happening in Mexico, but there is a need for more monitoring and documenting of what’s going on in the country, “ Ramos said.