After being murdered in 2012, Mexican journalist Regina Martínez was re-victimized through allegations that tried to smear her reputation.

Attacks on honor are a situation that many female journalists in Latin America face, in addition to other threats and aggressions, according to Sandrine Rigaud, editor-in-chief of Forbidden Stories, the global network of investigative journalists based in Paris that works to pursue the work of reporters who are threatened, censored or killed.

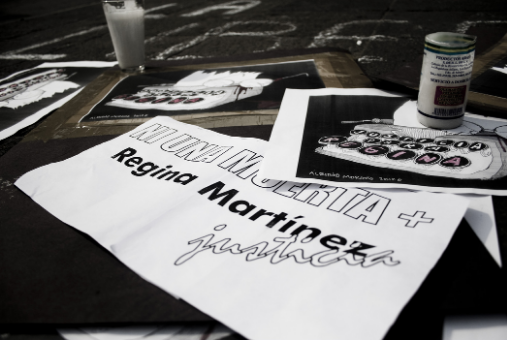

The investigation of "The Cartel Project" dedicated to Mexican journalist Regina Martinez's work was awarded with a Cabot Prize. (Photo: Adri Lagunes CC BY-NC 2.0)

The organization coordinated “The Cartel Project”, a journalistic initiative that investigated the global networks of Mexican drug cartels and their political connections, and whose efforts to continue the work of Martínez received a Special Citation this year as part of the Maria Moors Cabot Prize.

Rigaud talked to LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) and said that such recognition means an important reward for this unprecedented collaboration, in which 60 journalists from 25 international media and 20 countries came together in 2020 to take up the unfinished investigations of their murdered Mexican colleague.

According to Rigaud, Martínez led a continuous fight for the truth for more than 30 years. She investigated excesses of power and corruption ravaging the state of Veracruz, where she showed how politicians and organized crime interests colluded with one another. “The Cartel Project” exposes that eight years after Martínez’s death, those who ordered her murder have still not been arrested.

The Cabot Prizes are given by Columbia Journalism School in the United States and they “honor journalists and news organizations for career excellence and coverage of the Western Hemisphere that furthers inter-American understanding.”

This year, for the first time since their foundation in 1938, all winners are women journalists. They will receive gold medals and a $5,000 honorarium. The awards ceremony is scheduled for October 12, 2021.

LatAm Journalism Review: This year, all Cabot Prize recipients are women. What particular challenges do women journalists like Regina Martínez face reporting on Latin America?

Sandrine Rigaud: The situation is difficult for all courageous journalists in Latin America, whether they are men or women. But when you are a woman, you can be attacked differently, trying to smear your reputation to imply that you are not a professional or responsible person.

That's what they tried to do at the time of Regina's death: to make her out to be someone she wasn't, to imply that she was seeing men over to the house alone. For a while, the thesis of a "crime of passion" was circulated. For the colleagues of Regina who knew her and for her entourage, it was terrible. Not only did they have to fight to get the truth out, but they also had to fight so that the memory of their colleague was not soiled.

LJR: In recent years, the state of the media in Latin America –particularly in Mexico– has become increasingly challenging. What is your vision for the near future of journalism in this region?

SR: Since the publication of “The Cartel Project” in December 2020, journalists have been murdered in Mexico. The situation is of course still extremely challenging, but there is an awareness: the world discovered what Mexican journalists were facing every day, the threats they are under, the physical violence they can suffer. At the time of the publication, the Mexican president recognized that this drama should be a national priority. There is a lot of work to be done of course and there is a huge gap between political statements and the reality on the ground.

The situation of journalists is a reflection of a more endemic problem: the corruption of political elites with drug money. This is a pervasive problem, and unfortunately violence is not limited to journalists. As long as these deep-seated problems are not solved, the situation of journalists will remain extremely difficult.

Sandrine Rigaud is the editor-in-chief at Forbidden Stories. (Photo: @sandrinerigaud)

LJR: What does the Special Citation of the Cabot Prize for the investigation about Regina Martínez’s work represent for Forbidden Stories?

SR: It is a recognition of the incredibly courageous work of that highly-respected journalist who spent her career reporting on corruption, human rights violations, health scandals and drug trafficking.

Regina Martínez refused all forms of censorship, even as impunity reigned. She depicted the reality of a place where impunity silenced most dissident voices.

LJR: Why is collaboration a key element to continue the investigations of murdered journalists?

SR: As Laurent Richard, the director and founder of Forbidden Stories, wrote in 2018 at The Guardian, when “The Daphne Project” was published: “Cooperation is without a doubt the best protection. What is the point of killing a journalist if 10, 20 or 30 others are waiting to carry on their work? [...] Journalists are the enemy of the corrupt ecosystem that has been constructed. But what if this exposure becomes global, and the message amplified? Wherever you go, you will be questioned by the world’s press.”

With “The Cartel Project,” the crimes that Regina denounced made the headlines eight years after her death. The corrupt politicians that she was investigating were singled out by the international press. For the criminals who tried to silence her, it is a failure.

LJR: How did the team solve the difficulties of working on a case from different countries?

SR: The collaboration between journalists from different countries, sometimes separated by an ocean, was rather an asset. Thanks to the platforms that we use and the communication tools that exist today, it is easier to work without seeing each other. But getting sources on the other side of the world is not easy for a journalist working alone.

On the other hand, when you work hand to hand with a colleague who can confirm your information thanks to their sources, or a fellow journalist who can work on drug supply chains or on money laundering networks, it is extremely valuable. Collaboration is beneficial for everyone and it greatly increases the impact of your work.

LJR: What journalistic specializations are needed to develop investigations such as those that are part of “The Cartel Project”?

SR: You need to bring together almost every journalistic skill: data journalists who have access to huge leaks, journalists who have police sources, others who are experienced reporters and who know how to work in dangerous fields...

The most important thing you need to be part of an international collaboration like this one is to have a collaborative mindset. You can be the best journalist and not want to share your information. “Lonely wolves” still exist in our job! But what a project like “The Cartel Project” shows is that sharing information often pays off. And it's a great human adventure.

LJR: What piece of advice do you have for young journalists in Latin America reporting on narco-politics?

SR: Don’t hesitate to collaborate with each other and to promote collaborative journalism. When the crime is global, the response has to be global.

*Editor’s note: Rosental Alves, Cabot Board Chair, is founder and director of the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, which publishes LatAm Journalism Review.