Just over a month ago, the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul began experiencing the biggest climate disaster in its history. A combination of factors, such as the intense volume of rainfall, linked to climate change caused by human action, and failures in structures such as dikes and drainage pumps, led to the floods that affected 475 of the state's 497 municipalities. More than 580,000 people are homeless and, to this point, 172 deaths have been confirmed.

Journalists who live in the state and are dedicated to local coverage worked hard to report this climate tragedy, which also impacted many of them personally. LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) spoke to professionals from three native digital media outlets based in Porto Alegre, the capital of Rio Grande do Sul, who explained how they organized themselves amid the chaos to inform the population.

The waters that covered entire cities, destroyed roads and paralyzed the state did not stop journalism.

“Unlike other professions, journalism doesn’t stop,” Marcela Donini, editor in chief of Matinal Jornalismo, told LJR. “On the contrary: we have intensified our reporting.”

Part of Matinal's team. (Photo: Filipe Speck)

Matinal, a journalism and culture platform that emerged in Porto Alegre in 2019, produces investigative reports about the city and the state. It also delivers a newsletter on mornings from Monday to Friday, with its own content and curated news that may be of interest to its subscribers.

On May 3, a few days before the start of heavy rains and flooding in the south of the state, the center of Porto Alegre flooded for the first time since 1974. Matinal then began its extraordinary operation to cover the flood in the city, enlisting the entire team of 15 people, including those responsible for marketing and website administration, in covering the events.

“We focused 100% of the team on this coverage, which had already started very intensely. We continued at this pace until last weekend [May 26], which was the first weekend that I managed to have a day off since all this started,” Donini said.

In addition to extra editions of the newsletter, Matinal also sent extra editions of its newsletter in its WhatsApp community, Zap Matinal, with updates on the situation in the capital and the state to its readers. And it carried out an informative shift on his social media profiles, sharing not only links to his own content or content from other media, but also posts without links but with useful information for the population.

Meanwhile, everyone on the team was being affected by the flood, Donini said.

Zap Matinal, Matinal's newsletter on WhatsApp. (Screenshot)

“No one was homeless, but there were people who had to leave their homes, because there was a lot of flooding around their building, and they went to their family's house in a hurry. My father-in-law and his wife are at my house, for example, because their house is still under water. There were people who were left without water and electricity, because the electricity was cut off in the flooded areas and there were water shortages in many neighborhoods of the city,” she said.

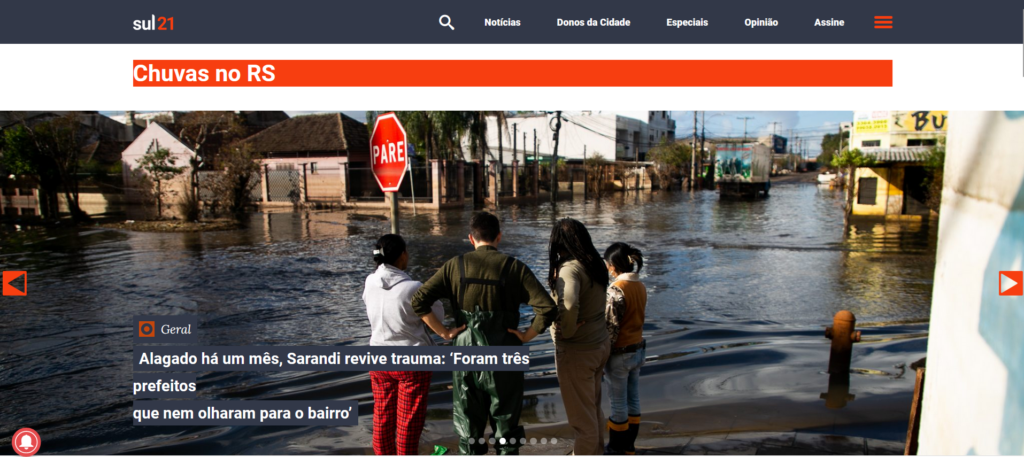

The Sul21 team went through a similar situation. The independent news site has been running since 2010 and has been managed since 2020 by its journalist collective. It provides local coverage centered on the city of Porto Alegre, but has covered the easing of environmental laws in Rio Grande do Sul since 2023, when three extreme weather events in the state left 75 people dead.

“Between Friday, the 3rd [of May], and Saturday, the 4th, was the moment when we realized that we were living in a situation that had never been seen before,” editor Ana Ávila told LJR.

She was the only person scheduled to be on call that weekend, but she soon understood that the entire team needed to be involved in coverage.

“We realized that there was no way anyone [alone] could do it. We reinforced and put practically everyone to work,” she said.

“Since then, we have been working under constant pressure, everyone has practically no time off and is taking turns. We’re also at the limit with physical structures, because we were all also impacted by the flood. Almost everyone had to leave their homes, because even where the water didn't reach, we started to run out of electricity, drinking water, and internet,” Ávila said. “There is chaos in the surroundings, in the entire city, and each of us is experiencing something.”

Part of Sul21's team. (Photo: Isabelle Rieger)

Thaís Seganfedo, director of journalism and editor of Nonada Jornalismo, had to leave her apartment to avoid being stranded in the middle of the flood. She and Rafael Gloria, executive director of Nonada, are married and saw the water rise and reach the building where they live between May 6 and 7.

“An Army truck came by asking if we wanted to be rescued. We decided to take our dog and head out early Tuesday [May 7] early in the morning. This later turned out to be the right decision, because the water rose and remained very high for two weeks,” Seganfredo told LJR.

National reach

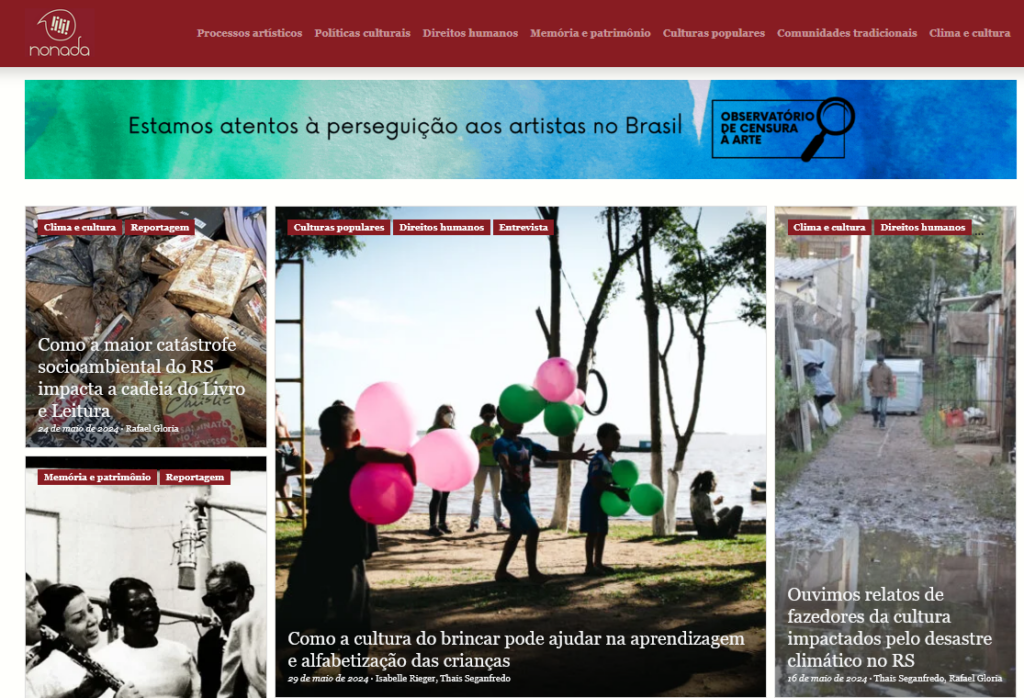

Seganfredo and Gloria founded Nonada in 2010 in Porto Alegre. Unlike Matinal and Sul21, which provide broad coverage of the city and state, Nonada is dedicated to culture, focusing on cultural policies, traditional communities, popular culture and memory and heritage.

In 2022, Seganfredo reported on the impact of the climate crisis on Brazilian cultural heritage. In January of this year, Nonada created the Climate and Culture section, which covers the intersection between the climate emergency and the cultural sector. Just over three months later, the media outlet’s main three-person team – Seganfredo, Gloria and reporter Anna Ortega – had to cover this situation in their own city.

“Seeing it happen here was surreal,” Seganfredo said.

Nonada's website. (Screenshot)

Nonada covered the floods in Rio Grande do Sul by mapping historical properties affected by the waters. Then, the team began to map cultural points and traditional communities affected. They also wrote articles about the impact of the climate disaster on cultural professionals and the book and reading sector, reporting the losses of libraries, bookstores and publishers' collections in the state. And it covered the work of cultural volunteers to bring art to children in shelters for homeless people – according to Civil Defense, more than 37,000 people across the state are in shelters at the moment.

Through an informal network of cultural journalists across the country, Nonada began to disseminate its work and encourage other media to republish it, as did the magazine Afirmativa, from Bahia, the magazine O Grito, from Pernambuco, and the magazine Fórum, from Sao Paulo.

“We wanted to provide coverage in order to help media outlets from outside Rio Grande do Sul,” Seganfredo said.

Sul21 and Matinal were able to base their coverage of the climate tragedy on the reports they do daily on the actions of public authorities in Porto Alegre and Rio Grande do Sul. As their teams know the local scenario and have relationships with sources on the ground, they knew how to where to look in this coverage and even reported on things that would lead to this tragedy.

“The precariousness of Dmae [Porto Alegre Municipal Water and Sewage Department], for example, has been an issue we have been working on since 2021,” Donini said. “We were always on top of it, so we were able to take advantage of our own coverage. We now continue with subjects that were already familiar to us, and we see some stories appearing later in other places as well.”

Sul21's website. (Screenshot)

Ávila cited an article that Sul21 published on May 14 about a manifesto signed by more than 30 experts, including former directors of Dmae and the Storm Sewer Department of the capital of Rio Grande do Sul. They denounced the lack of maintenance of the system that protects the city from flooding and suggested immediate measures to be taken by the authorities.

“We announced this the day after [the signing of the manifesto]. This document is only now having repercussions nationally. It appeared in Jornal Nacional [on May 23] and in other major national outlets, but we have been working with this document and producing stories and interviews based on it since the 14th. We noticed that little by little it starts to break through our bubble and reach other places, farther away,” Ávila said.

The three media outlets also saw the impact of their reports in the increase in post views and followers on social networks. According to Donini, Matinal's Instagram profile received 5,000 new followers, the reach of the posts increased by 623% and interactions with the posts grew by 1,200%. Audience on the Matinal website doubled in May, she said.

According to Ávila, the Sul21 profile on Instagram had an increase of 1,800% in reach and 611.5% in the number of interactions on posts. The Sul21 website saw a 200% increase in views in May.

Seganfredo said that a post on Nonada's Instagram profile about how leaders of African-based religions created a network to help communities of these religions in the state had more than 40,000 views. That became “the post we got the most reach and engagement with, by far,” she said. Also according to Seganfredo, profile reach increased 218% compared to April with 94,000 accounts reached, and engagement increased 188%. Nonada's website audience increased by 20%.

Matinal's website. (Screenshot)

Covering the floods presented material and emotional challenges to reporters, the journalists interviewed by LJR said. Safety equipment and working along with professionals from other media outlets proved necessary for them to be able to move through the floods.

Donini highlighted “a certain precariousness” of digital media outlets like Matinal, which is financed mainly with the support of its subscribers and still struggles to maintain financial health, and does not have the structure to report in the field in adverse conditions.

“One of our reporters said 'I'm going to go out and do an article,’ and I said 'but I don't even have galoshes to lend you, we weren't prepared for that, we don't even have a raincoat, I'm not going to put you in that situation.’ But he said ‘I have it, I can manage here,’ and off he went. (...) It was all done out of fear, but relying on the reporter's common sense, because it came from his initiative, and asking to be cautious and to not enter flooded areas and to do so as far away as possible,” she said.

The Nonada reporter went to the field in Porto Alegre, Seganfredo said.

“We were very concerned about her safety. Our reporter has even gone by boat [to the affected areas]. It is always important to ask every hour how she is doing and if she is safe. We've taken a class on this in the past, but we've never specialized in reporter physical safety. It’s something we have learned in practice and by talking to other colleagues here in the region,” she said.

Marcela Donini, editor in chief of Matinal. (Photo: Geovana Benites)

Seganfredo said that the first thing she thought about when starting this work was the need for courses focused on covering extreme weather events.

“If we had had this, we would have known much better and much faster what to do, how to do it, what equipment to buy, where to go. We didn't even know that. And the care, too. Anna [Ortega, the reporter], who is going into the water, had to take prophylaxis against leptospirosis. So if there were more courses, and I think there will be now, we would know much better [what to do],” she said.

At the height of the floods, it was difficult to move around the city, and Ávila commented that professionals from Sul21 worked with people from other media outlets to move around together.

“Our photographer is a young woman. I didn't want to put her in a situation of greater risk or greater vulnerability. So if they worked together and in larger groups, we felt they were a little safer and more protected,” she said.

Despite the difficulties, Donini said that a positive point is that the entire Matinal team was engaged in the coverage, aware of their responsibility to the public.

“I imagine that it was like this in other newsrooms too, because this is common. When an event imposes itself in this way, on this scale, anyone who works with pleasure and understands their purpose in an emergency situation easily engages in reporting. That doesn’t mean people aren’t tired,” she said.

Ana Ávila, editor at Sul21. (Photo: Luiza Castro)

Ávila said that one of the lessons learned from this coverage is that “we really need each other as communicators and journalists.”

“I have seen, for example, that other local outlets have tried to do investigative stories, in line with what we also do, to reflect a little more on things and not simply report the news. And we have complemented each other in one way or another,” she said.

This experience reinforced a sense of community among the journalists who dedicated themselves to this coverage and made them feel less alone, Ávila said.

“We have seen a lot of recognition for our work and a more collective view of communication,” Ávila said. “At many times we feel isolated in local journalism, doing coverage that is very much our own, something we know, that touches us, and sometimes very distant from the rest of the country or the rest of the media outlets. And I think this moment served to see that we are part of a larger network, of a community in some way.”