*This story was updated.

“At that moment, on the side of the Masp [São Paulo Museum of Modern Art], I was in a group of colleagues, and I said, 'look, it's calmed down, it looks like it's stopped' [the police repression of protesters]. As I said it, a tear gas bomb fell to our side. I pulled a colleague and [the police] started shooting again. I said 'it started again' and I took the hit.”

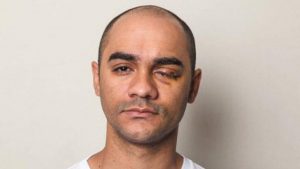

The scene took place 21 years ago, on May 18, 2000, and forever changed the life of Brazilian photographer Alexandro Wagner Oliveira da Silveira. Hit by a rubber bullet fired by the police, he was blinded in his left eye.

Alex Silveira: 21 years in search of justice for being blinded in one eye after being hit by a rubber bullet fired by the São Paulo police. Photo: Sergio Silva/Ponte Journalism

At the time, he was 29 years old and worked for Agora S.Paulo, a Folha Group newspaper. He was covering a demonstration by professors and health professionals on Avenida Paulista, in the heart of São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil. Last week, the Supreme Court (STF, for its acronym in Portuguese), the country's constitutional court and the last stop for legal cases in the country, recognized that he is entitled to compensation from the State.

“I have nothing to celebrate. Not on my personal side of history, for compensation for damages, nor for what this will contribute to strengthening democracy, security for colleagues and freedom of the press. Until now, nothing has been gained, nothing is secure,” Silveira told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) following the STF ruling.

Silveira's skepticism is justified by the 21 years of a costly, arduous and exhausting legal battle. In the first decision of the case, in 2007, the court recognized his right to compensation, but in 2014 everything changed: in the judgment of the appeal, compensation was denied with the allegation that the journalist himself was responsible for his injury for having remained at the scene of the conflict.

It took another seven years for the reversal in the STF, which, however, did not stipulate a deadline or amounts for the payment of the compensation to which he is entitled. Silveira's fear is that a new battle is needed over the value of fair compensation. At the first court level, this amount had been set at BRL 110 thousand (or USD $21,803).

“No one will be arrested, fired, spend years in prison, no one will apologize to me. The only thing that can make a difference is financial repair. (...) I don't believe there will be any improvement, for me or for the stability of the profession's security, if the fine is only symbolic. For it to have an effect, the value must be relevant and fair,” Silveira said.

At 50, he never abandoned photography, although he left journalism. He currently studies oceanography and works as a freelance photographer and 3D designer.

Silveira works today as a freelancer. In the image, a maned wolf photographed by him in the Serra da Canastra national park published in National Geographic Brazil. Photo: Alex Silveira

“I was never hired again in my life with a formal work contract. I only worked as a freelancer. [There was] a job offer, I sent my portfolio, they called me and learned of my situation and they dismissed me. This happened countless times,” Silveira said.

Photographer Sérgio Andrade da Silva is following the case closely. On June 13, 2013, he was covering one of the many demonstrations in the series of protests that swept through Brazil that month. Hit by a rubber bullet, he also lost sight in one of his eyes.

Injured in 2013, Brazilian Sergio Silva hopes to reverse a decision that found him guilty of having lost his sight. Photo: Alex Batista

“There was a big transformation in my personal and professional life. At the time, as I worked as a freelancer, photography was my only income. My career in journalism was interrupted by violence. I left the street, the action, reporting,” Silva told LJR.

At the time he lost his sight, Silva worked for the Futura Press agency and had been working for five years as a professional photojournalist. Today, he works with video production, with “still camera, on a tripod” and has returned to photography doing independent projects.

“I worked at a small agency compared to other outlets. I was looking for my space, looking to move forward in my career. My big goal, and it still is, is to get a space in a large media outlet in which I could contribute [with photojournalism],” Silva said.

His lawsuit against the State goes hand in hand with Silveira's. In the first instance, the Court understood that the responsibility for the injury was his for having exposed himself to risk during coverage. As the STF's decision in the other case is binding, Silva believes he will be able to reverse the sentence.

“The STF saying 10 to 1 that the State is responsible for an action brought about by public security agents is obvious. But the decision is not final, stating that the State must comply with our claim for compensation. And then we are talking about a reasonable indemnity so that, at the very least, it will give us support to repair the material damage that was caused to us,” Silva said.

In Peru, little hope on the horizon

The cases of the two Brazilian photographers are not unique in Brazil, nor in Latin America. Press freedom organizations collect cases of journalists injured during protests, some of which have serious lifelong effects.

Huallpa Cayo’s case was archived in Peru. Photo: courtesy.

Peruvian Rudy Huallpa Cayo was 24 years old when he took to the streets on April 1, 2014 to cover a demonstration calling for the completion of work on a hospital from the Melgar regional government. Injured in the eye by a rubber bullet fired by the police, he was never able to see again.

“I was almost ahead of the protesters. [A policeman] takes a gun, I see it, and he shoots. The pellet that he shoots, at a distance of 12 meters, falls to my left eye,” Huallpa Cayo told LJR. “The vision, you couldn't see it. I thought it was a [temporary] consequence of the impact. But, the doctors later told me that it would be irreversible."

The journalist continues in his profession, working at Diario Sin Fronteras, in Puno, but with little hope of receiving compensation from the State. According to him, the public prosecutor, which was supposed to investigate the case, asked for it to be closed due to an alleged lack of evidence to hold the police accountable.

“There were snapshots, testimonies, videos of fellow journalists, from when they shot, from when I fell. However, the public prosecutor asks us for a ballistic analysis, [but] I have not obtained an [independent] expert. When I say that I am suing a police officer, they withdraw. They did not want to carry out the ballistic analysis," the journalist said. “The trauma remains. I’m no longer a normal person. I’m a person with a disability."

Huaroto: ‘losing vision is like the worst nightmare because it is my work tool.’ Photo: Self-portrait

On Jan. 5, 2017, Marco Antonio Ramón Huaroto, also Peruvian, arrived late at a protest by residents of Puente Piedra, Lima, against the installation of a toll booth. At the time, he was an intern at newspaper Peru 21, of the El Comercio group. As soon as he learned that there had already been a clash between protesters and the police, he proceeded to look for the wounded. That's when the confrontation and repression by police resumed.

“It would have been 40 minutes, 45 minutes since I was at the side [of the protesters] and at some point, from that tank where they had already pointed at me several times, they fired a burst of pellets directly at the body and they hit me like five pellets in the head, in the hands, on the camera, too. And one of those pellets entered my left eye, and from that moment on, I already lost. I no longer remember very well. I just know that it knocked me back and that I started to see everything dark,” Huaroto told LJR. In his case, instead of a rubber bullet, the police used fired small lead balls.

As an intern, the journalist did not have health insurance and his family paid out of pocket for the cost of his treatment and the four surgeries that followed. Today, five years later, he has only 30 percent of the vision in his injured eye, has developed glaucoma, and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Even so, he has not gotten any redress and still accumulates medical debts.

“For a photographer, losing vision is like the worst nightmare, because it is my work tool, my mission. (...) I was no longer able to continue with a career that I was beginning to build and that I felt had many possibilities because I was doing well, because I was beginning to participate in exhibitions, I was beginning to participate in festivals and that ended abruptly,” Huaroto said.

A year after the incident, the photographer returned to the El Comércio group, but was fired in 2020, and has been working as a freelancer. Along with other colleagues, he created the collective Fotografxs AutoConvocadxs-FAC with the aim of serving as a protection organization for independent photojournalists, but also denouncing police violence and carrying out artistic activities.

“Regarding the news from Brazil, it seems positive to me,” Huaroto said, “because they have just done that, you are asking me these questions, and that I can give my testimony again after so long, it already gives me hope that there will not be complete impunity.”

*This story was updated to correct the type of projectile that hit Marco Antonio Ramón Huaroto. It was a lead ball, not a rubber bullet.