By Ramiro Silva

The year 2018 will see presidential elections in several Latin American countries, and with them, the risk of widespread misinformation caused by fraudulent news, often referred to as "fake news." In Brazil, concern about the problem has moved public authorities, and within four months of the election, the Superior Electoral Court (TSE, for its acronym in Portuguese) has made its first decision regarding the fight against fraudulent news in the electoral context.

On June 7, substitute minister Sérgio Banhos ordered that five texts about presidential candidate Marina Silva, from the Rede Sustentabilidade party, be deleted from the internet. According to a note on the TSE's website, he based the decision on a resolution passed in December 2017 that regulates election propaganda in the 2018 election.

According to the ruling, the party denounced to the court that a Facebook page called the Partido AntiPT "is allegedly publishing, repeatedly, made-up information that offends the political image" of Silva. The links were published on Facebook in 2017 by the page, which has more than 1.7 million followers. According to Valor Econômico newspaper, the posts refer to the website Imprensa Viva, linked to the anti-PT profile on the social network.

Banhos also gave 48 hours for Facebook to remove the posts with the content and 10 days for the company to provide access records to one of the posts, data on the origin of the registration of the page responsible for the publications and the personal data of its creator and administrators.

The minister noted that freedom of expression is guaranteed in the Brazilian Constitution, but that "its protection does not extend to anonymous manifestation" and that the absence of identification of authorship of the news "indicates the need to remove publications from the public profile." "Even if it were not so, I note that the information has no proof and merely states facts that are devoid of reference or source, with the sole purpose of creating a commotion about the person of the candidate," Banhos wrote.

Movements in Congress

With an eye on the elections, Brazilian congress members are also creating initiatives against fraudulent news. A Joint Parliamentary Front for Confronting Fake News was established on May 23, composed of 11 senators and 218 deputies.

According to Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, the front has the objective of putting pressure on the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Rodrigo Maia, of the Democratas (DEM) party in Rio de Janeiro, to put in motion bills that punish broadcasters of fraudulent news before the election, scheduled for October 7.

According to a survey by Agência Pública, 20 bills are going through the Brazilian Legislature with the aim of criminalizing everything from the creation of internet rumors to the publication of made-up news in the press, to the dissemination of false news. The penalties range from fines of 1,500 reais to up to 8 years of imprisonment.

In an interview with Folha, deputy Márcio Marinho of the Partido Republicano Brasileiro (PRB) of Bahia and the coordinator of the parliamentary front, said that the front is not intended to restrain journalists' freedom of expression. "We do not want to censor anything, on the contrary," he said.

However, associations of journalists and experts on the subject have already expressed concern about the Legislature’s initiatives. The executive director of the National Association of Newspapers (ANJ), Ricardo Pedreira, is one of them. "The debate about 'fake news' requires care, so that this phenomenon is not a smokescreen to undermine serious journalism, to prevent full freedom of expression," Pedreira told Folha.

Contradictions in the fight against fraudulent news

The journalist Natalia Viana, director of Agência Pública, published in the May 25 edition of the weekly newsletter of the publication her account of the debate about "fake news" that happened in the Chamber of Deputies on May 22, the day before the launch of the parliamentary front. According to her, the event became "an arena for attacking journalists."

Viana said that one of the guests of the event was Carlos Augusto de Morais Afonso, who, after a story from newspaper O Globo, was revealed to the public as the creator of the site Ceticismo Político (Political Skepticism). In March, the site helped to amplify fraudulent news about councilwoman Marielle Franco, of Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL), the day after her murder in the center of Rio de Janeiro. Anderson Gomes, driver of the car in which she was riding, was also killed in the attack.

According to the director of Pública, Afonso used his time in the debate in the Chamber of Deputies "to attack fact-checking organizations Agência Lupa e Aos Fatos." The two agencies were targeted by online attacks due to a partnership with Facebook, launched May 10, against the spread of fake news on the social network.

In the debate, Afonso presented the results of a "dossier" with posts from Lupa, Aos Fatos and Pública journalists from their profiles on social networks. In the document, journalists are ideologically classified as "left", "extreme left" or "undefined," and this classification is used to question the reputation of the agencies. "That is, exposing and attacking journalists for doing journalism," Viana wrote.

The Marielle Franco case

In March, even before the partnership with Facebook, the agency Aos Fatos carried out a check that helped to dislodge the fraudulent news that was circulating in social networks about councilwoman Marielle Franco after her murder.

False information about Franco was part of the intense exchange of messages and postings on Brazilian social networks in the days following her assassination, which at that time became the subject of greatest Twitter engagement in this decade in Brazil, as stated by Fábio Malini, coordinator of the Laboratory on Studies on Image and Cyberculture (Labic), from the Federal University of Espírito Santo (Ufes), to Radio Guaíba.

Rumors began to spread on Whatsapp, Twitter and Facebook the day after the councilman died that Franco had been married to Marcinho VP, a well-known Rio de Janeiro trafficker who has been serving a prison sentence of 48 years since 1997. Another rumor said that the councilwoman had been financed and killed by the criminal faction Comando Vermelho.

In a report published in the newspaper O Globo on March 23, reporters Marco Grillo and Gabriel Cariello, with the help of Labic researchers, identified that a link from the site Ceticismo Político with the rumors about Franco had been the most shared on Facebook on the topic. According to the Globo story, among the public figures who helped spread the fraudulent news were the Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL), which has 2.7 million followers on Facebook, Federal Deputy Alberto Fraga, of the DEM of the Federal District, and the judge Marília Castro Neves, of the Court of Justice of Rio de Janeiro (TJRJ).

On March 28, two weeks after the councilor's murder, Judge Jorge Jansen Counago Novelle of the TJRJ ruled that Facebook erase the posts with fraudulent news about Franco on its platform. At the end of April, Judge Luiz Fernando Pinto, also of the TJRJ, changed the decision to establish that the social network will only have to exclude pages whose links were pointed out by Franco's sister and girlfriend, who are the authors of the suit that asked for the exclusion of all offensive content about her on Facebook, as Folha reported.

Academic and corporate initiatives against the problem

Some academic research has been produced to identify the authorship of fraudulent news and the means by which it is disseminated. In addition to the aforementioned research by Labic, the Digital Political Debate Monitor of the University of São Paulo (USP) identified that more than half of the fraudulent news spread about councilwoman Marielle Franco were shared in family groups in Whatsapp, as reported by BBC Brasil.

The “Eleições Sem Fake” (Elections Without Fake) project, coordinated by Professor Fabrício Benevenuto, from the Department of Computer Science of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), aims to bring transparency to the media space. One of its tools is the "Bot or Human?" system, which allows you to identify whether users who promote hashtags and trending topics on Twitter in Brazil are human or robots, and it singles out fake profiles.

Facebook and Whatsapp, the two most used social networks in Brazil, also announced measures to curb the spread of fraudulent news. As Folha de S. Paulo reported, Whatsapp has created a three-pronged strategy against the problem. The first group of actions will be targeted at users, who will be able to report and block unwanted content, and also includes identifying messages that are relayed from one user to another. The second measure consists of mechanisms to detect spam, or messages sent in high quantity, via metadata. For the third front, they will try to approach the Brazilian Electoral Justice and other public agencies, in order to respond promptly to judicial orders that point to electoral manipulation and dissemination of false news.

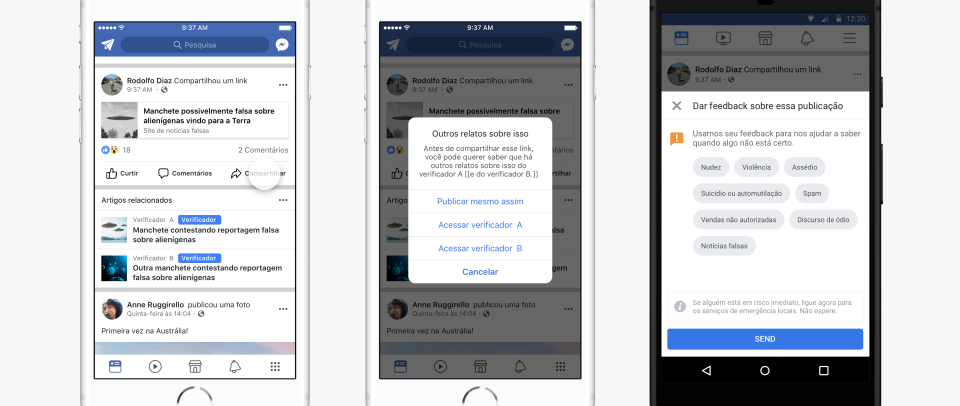

Facebook announced its partnership with Brazilian fact-checking agencies Aos Fatos and Lupa to combat false news on the social media platform. (Facebook)

Mark Zuckerberg, co-founder of Facebook and owner of WhatsApp, has included efforts against false news in the social network’s resolutions for 2018. "We won't prevent all mistakes or abuse, but we currently make too many errors enforcing our policies and preventing misuse of our tools,” he said, according to CBS News.

In partnership with the agencies Lupa and Aos Fatos, the social network debuted its news verification program in May in Brazil. The initiative was launched in December 2016 in the United States and has since been implemented in several countries, including Mexico, Colombia and India, in partnership with member fact-checking organizations of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN).

The agencies have checked the posts that network users flag as fake. If the content is indeed considered false by the checkers, they will have their organic distribution reduced and can not be boosted. Pages that repeatedly share content that is considered to be fake will have their reach diminished and will not be able to advertise to increase their number of followers.

People and page administrators will also be notified, when they try to share content considered to be false, that their truthfulness has been questioned by the agencies. The text with the check may also be associated with the questioned content, so that it reaches the user’s timeline accompanied by the verification that flagged it as false. Facebook claims that in the U.S., this method has reduced the organic distribution of news that is considered false by verification agencies by up to 80 percent.