At the beginning of July, Brazilian journalist Lúcio Flávio Pinto announced on his blog, which he has been updating several times a day since 2014, that he had decided to end his "daily public journalistic activity." Colleagues and readers received the announcement with sadness and perplexity. With 57 years in the profession and about to turn 74 years old, Lúcio Flávio Pinto is synonymous with independent and intrepid coverage of the Amazon and the corruption of political and economic powers in the region.

In a conversation with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR), Pinto spoke about his decision and the state of his health and reflected on his career. He also criticized the press in Pará, the state where he was born and where he works, and nationally, especially regarding journalistic coverage of the Amazon.

"Covering the Amazon is expensive. You have to travel a lot, and that is expensive. The local press no longer does this, it reproduces what the national press publishes. What the national press publishes is the result of public figures, researchers, NGOs who dictate what should be established because they have the primary source. Journalists no longer go to the primary source, they go to the intermediaries and repeat what they say, they do not question," he said.

Lúcio Flávio Pinto in 2016. (Photo credit: Paulo Santos / Acervo H)

Asked what he would say to young journalists covering the Amazon, Pinto said he would urge them to be "a character from I-Juca Pirama, the famous poem by Gonçalves Dias: Children, I saw it.'"

"If you write about a tree falling, be there to see the tree. If you didn't see the first [falling tree], see the second. If you know about a major land conflict in the interior of the Amazon, go there. If you don't hear the first shot, hear at least some. Don't be seduced by the power of the computer. Get out from behind a screen and go to the field," he said.

From his beginnings in 1966 as a journalist in Belém, the capital of Pará, Lúcio Flávio Pinto dedicated himself to doing local investigative journalism with national and international relevance. This was recognized by the various awards he received throughout his career, including the Colombe d'Oro per la pace in 1997; the International Press Freedom Award from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) in 2005; the tribute at the Congress of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji, by its Portuguese acronym) in 2009; the Vladimir Herzog Special Award in 2012; and his distinction by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) as one of the 100 Information Heroes in 2014, where he was the only Brazilian on the list.

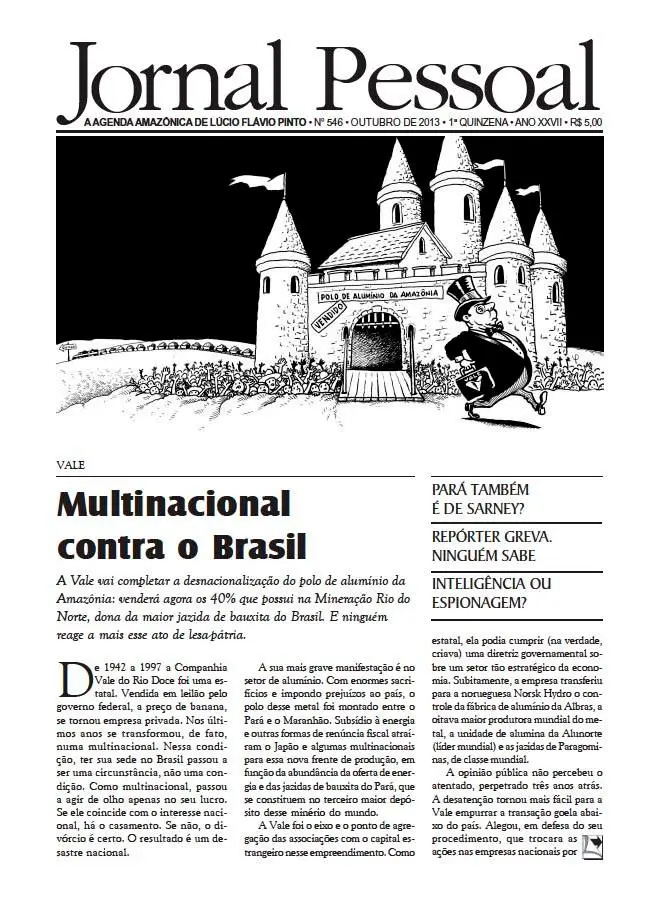

He worked for local and national newspapers, including coordinating an Amazon branch of the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo in the 1970s, which had reporters based in all the capitals of the region. In 1987, he founded Jornal Pessoal [Personal newspaper], a one-man newspaper: Pinto conducted investigations, wrote stories and analysis, laid out the newspaper, took care of the printing and distributed it at newsstands in Belém every 15 days. He did so for 31 years, a period in which he never accepted advertising in the newspaper and supported it with sales and contributions from readers, in addition to taking money out of his own pocket. In December 2018, its last edition circulated.

"I can't make journalism a professional instrument. It is, in fact, the instrument of causes I’ve had and have, since many decades ago," he said, explaining that in July 2019, he tried for the first time to move away from "everyday, breaking news, frontline journalism," as he wrote on his blog. At that time, he was already feeling the advance of Parkinson's disease, diagnosed in 2016.

"I've wanted to stop everything since then. I would stop for a few days and come back again, because I would learn about things that had not been published anywhere, as happened in 1987 with Jornal Pessoal. It came about because of the murder of a former state deputy, a very serious case of a planned assassination, and no newspaper published the names of those involved," he said.

Pinto said he spent three months investigating the murder of former deputy Paulo Fonteles de Lima, who died in June 1987, and created his Jornal Pessoal to publish that story.

"I published a story giving the names of everyone: middleman, intellectual author, etc. I was going to do just that issue, but then there was an embezzlement at Banco da Amazônia and none of the newspapers wrote about it, because they were involved. So I went on from there because of the silence of the press. Silence that isn’t free," he said. Pinto alleges that the main press in Pará is allied with governments and companies involved in corruption schemes and predatory exploitation of the Amazon.

An October 2013 issue of Jornal Pessoal. (Screenshot)

Throughout his career, he was the target of 34 lawsuits. Two are still open, both filed in 2005 by brothers Rômulo Maiorana Jr. and Ronaldo Maiorana, heirs of Grupo Liberal, a conglomerate of companies in Pará. Among them are TV Liberal, a Rede Globo affiliate in the state, and the newspaper O Liberal, where Pinto worked in the 1970s and 1980s.

Pinto has written extensively about what he calls the "largest communication complex in northern Brazil," as he said in the introduction to his book "A lethal weapon - The press of Pará," released in 2015 and one of 21 books he has published.

On Jan. 21, 2005, Pinto was assaulted and threatened by Ronaldo Maiorana, then-director of the newspaper O Liberal and now president of Grupo Liberal. According to Pinto's account published by Abraji, he was having lunch with friends at a restaurant in Belém when Maiorana, accompanied by two security guards, approached him and punched him. Pinto said he was "grabbed by the collar, thrown to the ground and kicked by Maiorana and the security guards, repeatedly, when he tried to get up.. The businessman also allegedly threatened to kill him.

Pinto filed a complaint with the police, which resulted in a lawsuit that led to Maiorana being ordered to pay a fine equivalent to 50 minimum wages. "Not in cash, but as a provision of food baskets to charities, one of which is very close to the [Maiorana] family," Pinto wrote.

In his post "Pardon me, readers," published July 8 on his blog, Pinto explained that he decided to interrupt his "daily public journalistic activity" when he realized he had committed an error in a text published on the blog days earlier. He attributed this "cognitive failure" to worsening Parkinson's disease.

"In all my journalism life, of more than 57 years, I have faced aggressions, threats, lawsuits because I was perfectly confident of what I published," he said.

"I’ve even established my confidence against attempts to assault me on the assumption that I have proof of everything I say. When I had this incident a few weeks ago, what was in question was my ability to discern the data with perfect lucidity before publishing it. Hence I got a very big jolt, because Parkinson's has reached the cognitive part. I saw the information and read it differently," Pinto said.

Although he has decided to end his original journalistic production, he intends to continue writing on his blog and disseminating the work done in these almost six decades. Pinto hopes that by slowing down the pace of his work, he will be able to slow the progression of the disease.

Lúcio Flávio Pinto in 2016. (Photo credit: Paulo Santos / Acervo H)

"It's a distressing thing," he said of the difficulties imposed by Parkinson's disease. "It shakes me a lot because maybe these episodes will repeat, and if that repeats more often, then I’ll stop writing altogether. It's a factor that I can't fight anymore, if it repeats itself," he said.

Pinto's text about his decision to leave daily journalism resonated among other journalists, especially those who have known him and followed his work for several decades.

Marcelo Beraba, co-founder and first president of Abraji, sent the text to colleagues of the association the day after its publication. "It is a text of honesty and commitment to journalism, and it really moved me. I do not remember, in these more than 50 years of journalism, reading anything stronger, more courageous and more honest. A moment of reflection on our lives, our limitations and our commitment to ethical journalism. A lesson in ethics and courage," he wrote.

Speaking to LJR, Beraba said he has known Pinto "for decades, I don't even remember since when.”

"I worked at Globo in Rio in the 1970s and followed his work as a correspondent for Estadão in the Amazon. It was a period of military dictatorship, censorship, public policies and harmful projects for the Amazon — and there was Lúcio Flávio investigating and reporting. He had to have a lot of courage and discernment. This willingness and commitment to closely monitor public spending and the consequences of projects and programs for the people of Belém, the state of Pará and the far reaches of the Amazon remained intact, even after he left the traditional press and created his own journalistic outlet," Beraba said.

In response to Beraba, journalist Miriam Leitão, also a member of Abraji and honored by the association in 2019, said Pinto's text "is a lesson that goes beyond journalism."

"I met Lúcio Flávio in the early 1980s when I went to cover Pará," Leitão told LJR. "His work is a forerunner for covering the Amazon with concern for the environment, Indigenous rights, and the constant denunciation of collusion between economic and political groups in the region. His journalism faced all kinds of economic blockades and judicial persecution and [yet it] remained. His work can be defined as long resistance. And it will continue to be. His texts have been a reference source for other journalists," he said.

Kátia Brasil, co-founder and co-director of the agency Amazônia Real, where Pinto has maintained a weekly column since 2016, told LJR that she got to know his work by reading Jornal Pessoal in the early 1990s. "Lúcio Flávio has always been a fighter for good journalism," she said.

From left to right, journalists Kátia Brasil, Leonêncio Nossa, Lúcio Flávio Pinto, Paulina Chamorro and Eliane Brum in 2015. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Kátia Brasil)

"In Pará, the power the press has in relation to political and business events is very evident. Especially regarding deforestation in the Amazon, mining, large corporations that invest millions of dollars to exploit mineral and forest resources in the state. We don't talk about the environmental impacts or the devastation in Indigenous territories, and Lúcio Flávio has always brought that in Jornal Pessoal," she said.

Brasil also said it was "an honor" to have him as a columnist at Amazônia Real. "He teaches me too much, especially to be patient, to know how to face challenges, which are many, and to face the powerful, those people who file lawsuits against our work and manage to censor our stories (...) He, who has already been faced with so many impacts, always has a word of comfort, of hope, of never giving up," she said.

Pinto told LJR he was "very happy" with the expressions of affection and solidarity he has received from colleagues and readers in recent weeks, but lamented that "the best and most intense messages came from outside Belém, outside Pará, outside Brazil."

"It seems that the farther my reader is, the more generously he evaluates me. Because those who are here know they cannot count on my pen to serve friendships or interests. I have no friends when I sit down to write. The devil commands me. I say, 'Devil, please, I don't want to write this about this guy, he's such a nice guy...' And the devil says 'write it!' And God says: 'It's your fight with the devil in the land of the sun,'" he joked.