"For me, it was very hard when I photographed Yolanda Ordaz's objects, particularly a cap that she wore, because since she died ... or since they murdered her, the cap remained inside a gift box," Félix Márquez said in an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "And when I opened that box, Yolanda's scent was still there."

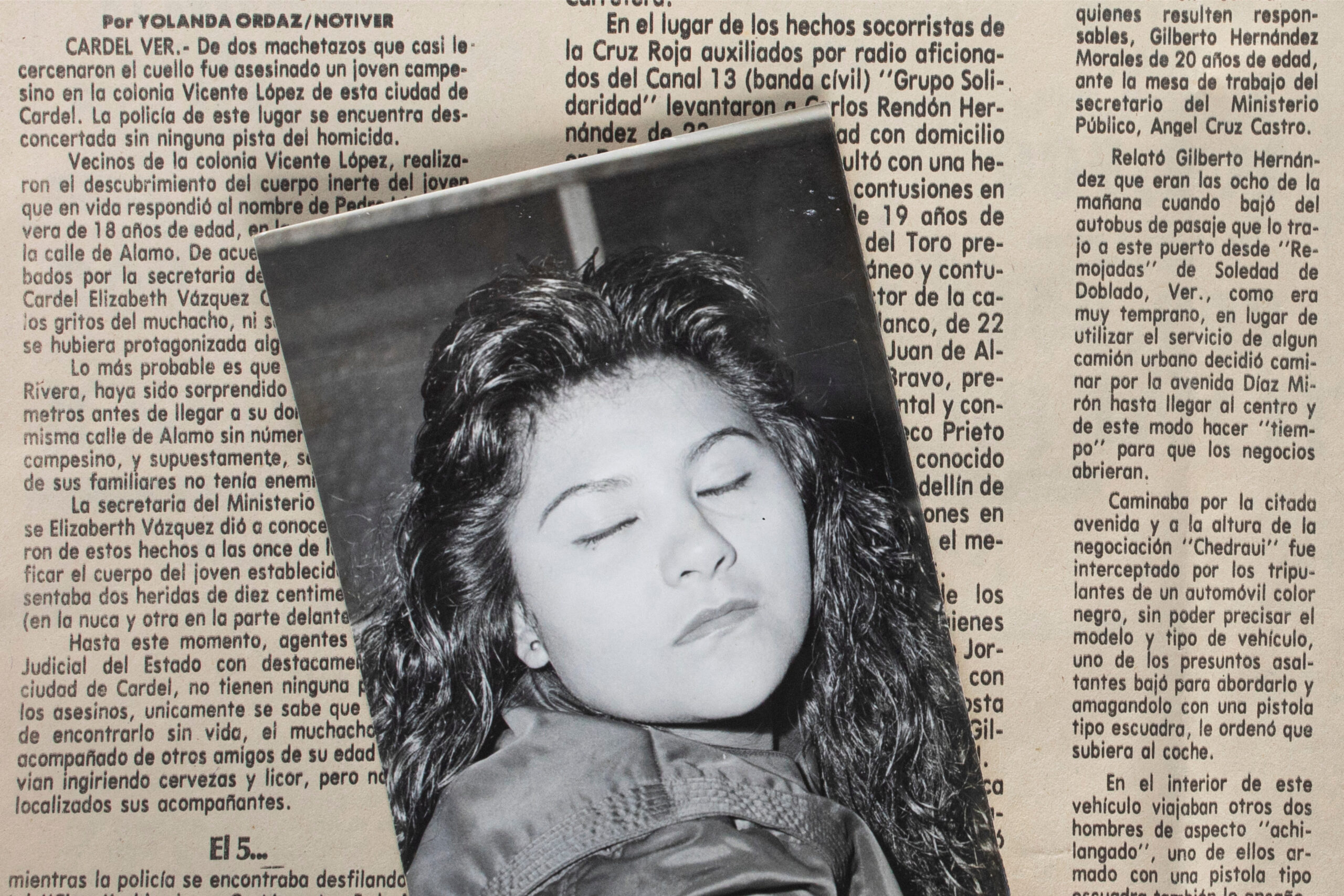

Photograph of family album and article by the Veracruz journalist Yolanda Ordáz de la Cruz, who worked for the newspaper Notiver. (Photo: Félix Márquez)

Márquez, 32, is a photojournalist born in Veracruz, currently a correspondent for the Associated Press in his country, and a contributor to various national and international media. He often covers the war on drug trafficking, migration, human rights and children's rights in Mexico.

In 2015, the photojournalist decided to contact some of the families of his murdered Veracruz colleagues, many of them his friends, to photograph the objects that identified them. They were things they used or carried with them when reporting, as well as photos from family archives.

Proyecto Vestigios (Vestiges Project) –launched initially on Instagram and later on its own site on Dec. 6– is more than a journalistic investigation, “it is a work of personal introspection,” Márquez said. It includes seven journalists killed in Veracruz between 2011 and 2015.

The images of the project are also accompanied by a short and concise text on the journalists’ deaths.

During the administration of then-governor of Veracruz Javier Duarte (2010-2016), Article 19 documented the murder of 17 journalists. From 2000 to 2020, there have been 30 deaths of journalists in Veracruz, with the Duarte government being the most lethal period for communicators in that state, according to data from the organization.

"Félix is a very committed photojournalist, I have known him for several years and we know each other through tragic situations," Marcela Turati, co-founder and editor of Mexican investigative site Quinto Elemento Lab, told LJR.

In 2019, Márquez won a scholarship from Article 19 that financed investigative projects, with editorial support from Quinto Elemento Lab.

With this scholarship, the photojournalist managed to finish his project, although the pandemic delayed the entire process because he could no longer have contact with the relatives of his colleagues. "These were very tense months for the project," Turati said.

In recent years, Márquez has spoken repeatedly with many of the families of the deceased to ask them what they remember about their loved ones and, at the same time, ask himself that same question to make sense of the objects that he has chosen to highlight to tell the stories.

Among the journalists in this first installment is Yolanda Ordaz de la Cruz, a reporter for the newspaper Notiver with more than 20 years of experience in nota roja reporting. She was abducted, tortured and found dead on July 26, 2011.

“Although I did not work with her for as long or as closely as some other colleagues, well the times I met her she was always perfumed. And well, opening that box where the cap was, made me…, I mean, it was very hard,” Márquez said.

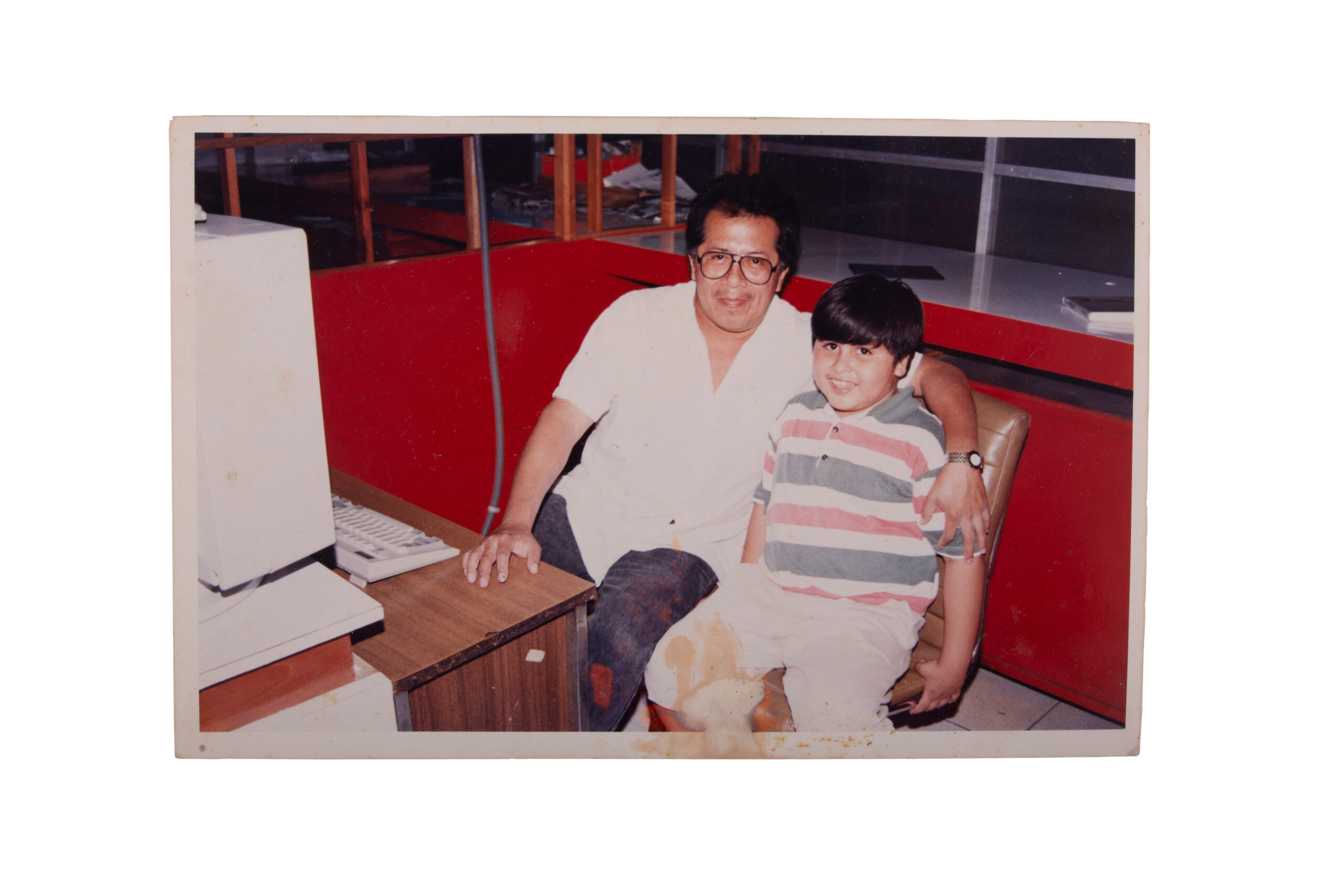

Miguel Angel López Velasco and Misael López Solana, father and son in the newsroom of the Newspaper Notiver in the 1990s. (Photo: Félix Márquez)

It also includes Miguel Ángel López Velasco, known as Milo Vela, and his son Misael López Solana, who were massacred in their home, along with their wife and mother, at dawn on June 20, 2011. Father and son worked for Notiver: López Velasco as editor-in-chief and his son as a photojournalist.

“From my point of view, [‘Milo Vela’] was the best nota roja journalist in the state of Veracruz and the one with the most experience, books, contacts. And his son always grew up in the Notiver newsroom,” Márquez said. One of their objects included in Vestigios is a photograph from the family album, where López Solana appears as a child, together with his father, in the Notiver newsroom. "Misael was my friend," Márquez recalled.

The project also tells the story of reporters Guillermo Luna and Gabriel Huge, who were murdered in Boca del Río, Veracruz, on May 3, 2012.

“They were uncle and nephew. Gabriel Huge brought Guillermo into the world of news and nota roja journalism. They were both abducted and murdered on the same day, in a very brutal way,” Márquez said.

Among Luna's objects is the camera with which he worked. It was a camera that no longer had a shutter button and taking pictures with it was difficult. Luna was young, wore sports T-shirts, sunglasses and liked reggaeton, said Márquez, who used to come across the journalist on various commissions.

Guillermo Luna's camera used while working for VeracruzNews and El Regional newspaper until the day of his murder. (Photo: Félix Márquez)

Gregorio Jiménez, found dead on Feb. 5, 2014, and Moisés Sánchez, abducted and murdered on Jan. 2, 2015, complete the group of journalists honored by the project.

From his taxi, using a megaphone, Sánchez narrated news about his town that he included in his newspaper, which he wrote by hand and then photocopied to distribute in his district. That megaphone is one of the objects Márquez chose to photograph for his project.

An emblematic case of murders of journalists in Veracruz is that of Regina Martínez, who was brutally killed at her home on April 28, 2012. Márquez tried to include her in this first installment of the project, but Martínez's relatives were unable to grant him an interview.

According to Turati, as a consequence of Martínez’s murder, a small collective of journalists critical of the authorities was formed, and Márquez was part of this group.

Regarding the aesthetics of the photos, Márquez looked for different formats to portray the objects of his colleagues in the best way.

“I opted for the white background and artificial lighting to highlight each of the details of the object, such as the dust, scaling, rust, plastic wear, etc. This was in order to demonstrate the passage of time through them, and white was a background that left nothing to the imagination, nor does it take away your attention. My closest reference in this project is forensic photography,” the photojournalist said.

Vestigios has been shown in 2020 as part of the United Nations Journalists at Risk virtual event. In 2019, it was shown in Fredrikstad, Norway, during the DOK Festival. And in 2018, some images from the project were shown at the Bronx Documentary Center in New York and at Photoville.

France’s Le Monde and The Washington Post of the U.S. published the recent official launch of Vestigios, accompanied by the international journalistic investigation about the 2012 murder of Mexican journalist Regina Mártinez. Twenty-five journalistic media from different parts of the world, under the direction of Forbidden Stories, participated in this report called The Cartel Project.

“We are very honored, at Quinto Elemento and I also know at Article 19, to be able to contribute and help incubate these documentation and denunciation projects through art, through photography, of what has happened in Veracruz and about these murders and disappearances that should not have happened, that we must remember,” Turati said.

“Veracruz is the biggest cemetery of journalists,” the editor emphasized.

Márquez plans to make a second installment of the project in which he will include colleagues killed outside of Veracruz. In this second part, he plans to include photojournalist Rubén Espinosa, his great friend and colleague, who was shot dead in Mexico City on July 30, 2015 along with a group of four people.

"For me, Rubén was one of my best friends within the profession and to date I have not been able to photograph his objects because I don't dare to do so," Márquez said, moved.

Days after Espinosa's death, Márquez had to leave Mexico, as the topics the two covered were very similar and he felt that his life could be in danger. With the help and connections of his colleagues and friends, he managed to go into exile in Chile for a year. He returned to Mexico in 2016.

"I would like not to have to photograph more murdered comrades," Márquez said. "Unfortunately, we are in Mexico, one of the most dangerous countries to practice journalism, but I would like Vestigios to end soon."