With a podcast, a book of crónicas with thoughtful photographs and a mini-documentary available in Spanish and English, the publishing house of the Peruvian University of Applied Sciences (UPC, for its acronym in Spanish) portrays the dignity of eleven men experiencing homelessness by telling their stories.

Team of the UPC multimedia project Casa de Todos, left to right: José Vidal, Carlos Fuller, Luis Cáceres, Úrsula Freundt-Thurne and Franz Krajnik. (Courtesy)

The project "Casa de Todos: faces of the street in Plaza de Acho" was planned and carried out in 2020, during the first months of the declaration of a national emergency and mandatory quarantine in Peru due to the coronavirus pandemic. Between June and July, the Peruvian communicators José Vidal and Franz Krajnik took the photographs, and Carlos Fuller and Luis Cáceres conducted the interviews with people who lived on the street and are now sheltered in a tent erected in a bullring in the historic area of Lima. The project was published at the end of the year.

The initial idea for the project was different, but the pandemic and confinement, as they did to everything, forced a change of plans. Úrsula Freundt-Thurne, dean of the UPC College of Communications and editor of the project, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) they managed to carry out the project, despite the change of topic, thanks to the Erasmus grant from University of Hertfordshire in the UK. "It ended up being a very dignified journalistic project," Freundt-Thurne said.

After the strict quarantine imposed by the Peruvian government since March 15, 2020 to mitigate the aggressive spread of the new coronavirus, the the Society of Charity of Metropolitan Lima, with the support of the Municipality of Lima, decided to make the Plaza de Toros de Acho into a temporary shelter for poor and homeless people. In this plaza, one of the oldest in Latin America, these people receive medical care, food, clean clothes and a bed to sleep in.

The Plaza de Toro de Acho had not interrupted its bullfighting seasons in 74 years, according to EFE.

Carlos Fuller interviewing people inside Plaza de Toros de Acho. (Photo: Franz Krajnik)

The book, which is free and is both in digital and print version, is made up of six chapters: street, square, house, life, community and identity. Within the chapter ‘life,’ the stories of eleven characters who now live in this temporary shelter are told, which will later have a fixed location in another part of Lima. The journalistic crónica and the photographic essay are the means with which these stories and this social initiative born during the emergency are explored.

Among these stories, Fuller, Cáceres, Vidal and Krajnik –all professors at the UPC College of Communications– tell the life of a 70-year-old man who plays the flute and claims to be the Holy Pontiff of Peru. In another story, they narrate the life of an 83-year-old man who, by dedicating himself so much to aeronautics, neglected his own family. They also portray the twists and turns of fate that led a Nigerian and an American to end up lost in limbo on the streets of Lima.

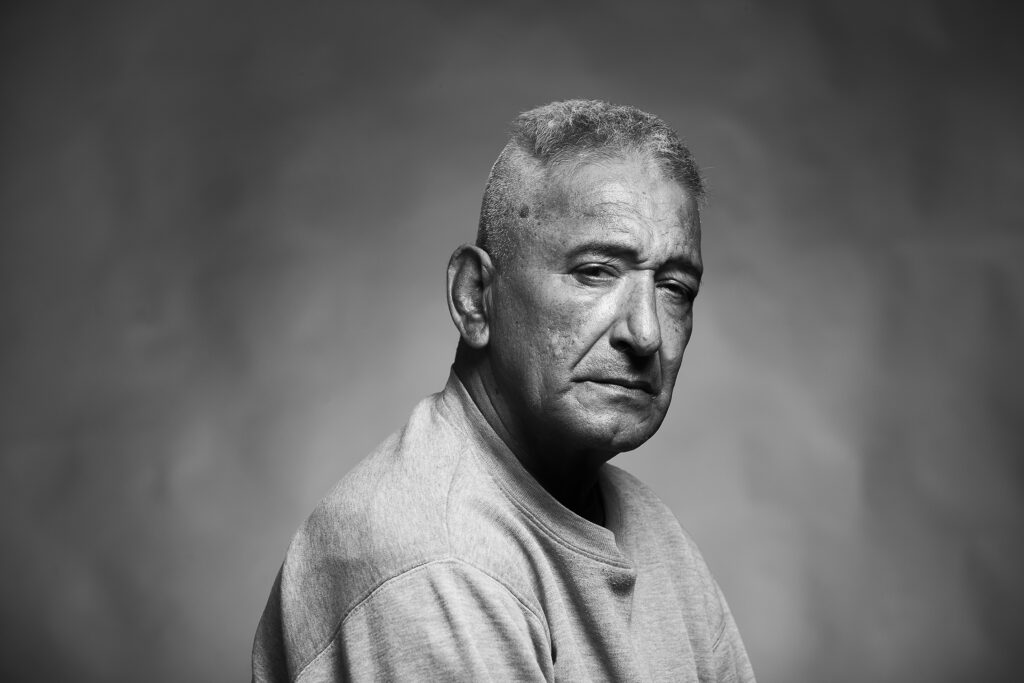

In the photographic part, Krajnik said, an attempt was made to portray these characters through their gestures and the harshness that their faces conveyed. However, he said, an attempt was also made to recover the most human part of each of them.

Photographs by renowned documentary photographers Joseph Koudelka, Alberto García-Alix and Robert Frank served as inspiration for Vidal and Krajnik in portraying the project's interviewees, the photographers explained.

Many of the people portrayed have suffered from alcoholism, drug addiction, have committed crimes, or have been abandoned by their families due to a disability or being elderly. The photographs, in black and white, tried to evoke that past.

“That responds a little to what we wanted to understand, we wanted to see the nostalgia for what these people have experienced, trying to respect, with black and white, that drama that they had lived on the street. But, at the same time, we were not photographing them in the street, we were photographing them inside the bullring. So there, in a way, their present comes together in the bullring, with the past of their drama and their personal stories,” Krajnik said.

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI), in 2019, 20.2 percent of Peru lived in a state of poverty, as published by RPP. With the pandemic, the Central Reserve Bank projected that the poverty rate would rise to 27.4 percent in 2020, the site reported.

The shelter houses approximately 120 homeless people. The characters portrayed in the project were chosen from the information that the medical staff had recorded.

However, as happens in journalism and other fields, one of these people came to them by chance. "Come here, nephew! I want to tell you something," Víctor Manuel Sono Neira, 76, told Fuller, while the journalist walked through the bullring in his protective suit, almost space-like, as the journalist told LJR.

Portrait of Víctor Sono Neira by Franz Krajnik.

Sono Neira turned out to be one of the most controversial people portrayed in the project, according to the journalists. He was an ex-convict who before entering Casa de Todos sold candy on the streets. Sono Neira told Fuller in one of the interviews that he had asked God for a bed and bread to eat. “What else am I going to ask? Who am I to ask? I'm rubbish, brother. Do you think I deserve this? I have hurt, man. I have killed people, brother. I have made my family suffer,” Sono Neira told Fuller, according to what the journalist told LJR.

The project took just over six months, with Zoom meetings every week, between the interview period and the editing of the book and the documentary.

The pandemic not only changed all the logistics of the investigation, but also forced them to wear all kinds of accessories and suits to protect themselves, in addition to making it difficult to verify the data of the interviewees.

“We were always in the white suits, like astronauts, the jumpsuits, the masks and the goggles. We could not enter the ring if we did not dress with the jumpsuit or mask,” Krajnik said.

The process of verifying the information provided by the interviewees was also one of the challenges of carrying out this project during the pandemic, since many institutions were closed and many people were reluctant to interact with the journalists.

“The institutions that could help you verify certain data were neither open, nor could they assist you, nor did they want to assist you. So we had to look at alternative ways of verifying: calling family members, talking to other people, etc.,” Fuller said.

There was another particular case the journalists recalled, the story of American Barry Wallace Frank, Cáceres told LJR. “He is a professor of technical English in oil and mining fields around the world,” Cáceres said. Wallace lived in the vicinity of the housing complex Residencial San Felipe.

To verify his information, “I had to go to Residencial San Felipe to interview his neighbors, to interview his friends, his best friends, who lived with him for a year that he was practically on the street, or sleeping in abandoned cars, as if he were a cat,” he added.

For the podcast, Freundt-Thurne said, the structure of the story changed somewhat and four of the eleven characters featured in the book and photos were chosen. The four episodes of the podcast are four moments in the lives of these four people, which end on a note of hope, the editor said.

“We have quite a few dreams regarding the project, because we think they are the stories of all of us,” Freundt-Thurne said. “You don't have to be homeless to have that story, we all have a relative who has lost their way. And I think it's a way of explaining to the new generations that you have to do things well and that you have to worry about those around us.”