On the occasion of the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, LatAm Journalism Review highlights four emblematic cases in the region that remain largely unpunished.

More than half (56 percent) of the murders of journalists in Brazil over the past three decades are in “complete impunity,” meaning that no one has been convicted for these crimes. That’s 25 of the 44 journalists killed for their work in the country since 1992, according to statistics from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

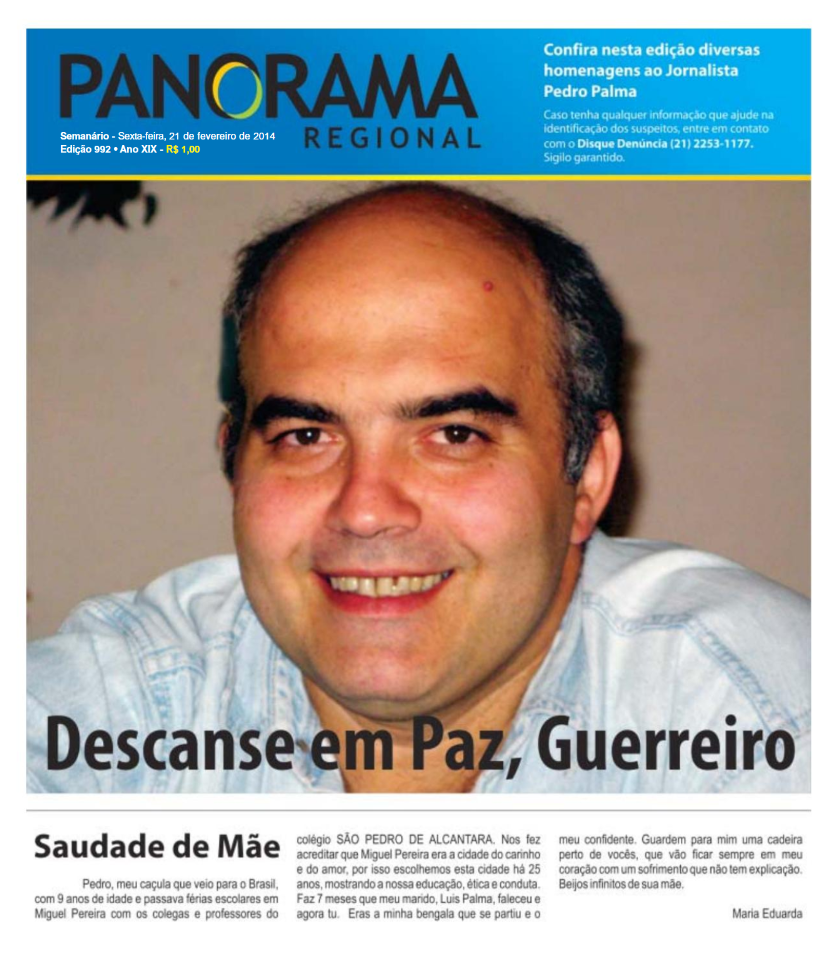

Pedro Palma, owner of the weekly newspaper Panorama Regional, is one of those 25.

Palma was murdered in broad daylight in front of his home in the municipality of Miguel Pereira, in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro, on Feb. 13, 2014. Nine years later, the investigation into his killing remains open and no one has been held responsible. His case illustrates the obstacles to holding accountable perpetrators and masterminds of crimes against journalists in Brazil.

Negligence, communication problems among the responsible authorities, and the fact that the police investigation has been kept confidential, are some of the factors contributing to the impunity of Palma's murder, according to the international initiative A Safer World For The Truth. A collaborative project between the organizations Free Press Unlimited (FPU), CPJ and Reporters Without Borders (RSF, for its acronym in French), the initiative investigated Palma’s case between 2021 and 2022 and published the report “The Case for Transparency: Opportunities for Justice in the Case of Pedro Palma and Beyond” in April 2023.

February 21, 2014 edition of the newspaper Panorama Regional honored Pedro Palma. (Panorama Regional)

Jos Midas Bartman, research coordinator at FPU and one of the report's authors, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) that, compared to other cases of impunity in journalist murders that he analyzed in other countries, “this is not an investigation that's completely botched or where there was a clear obstruction of justice.”

“It wasn't that bad. I do believe that the authorities hoped to have made progress with the investigation, but there were structural issues that prevented it from leading to justice,” he said.

For the researcher, Palma's case is representative of the murders of journalists not only in Brazil, but also in several countries. Globally, local journalists working in small outlets, which they often own, are much more targeted than journalists working in large outlets in capital cities, he said.

“[The journalists who are killed are] usually reporters that cover the relationship between organized crime and politics, corruption and embezzlement, are critical toward local power holders and do not have the protection from the limelight of the capital,” he said. “They're often in a municipality, working for their own media, and do not have the protection of large media organizations. But they are still able to criticize certain people, and not just criticize, but pull the skeletons out of the closet and get attention with their stories.”

Palma was editor-in-chief and owner of the weekly Panorama Regional, which he, his wife and his father founded in 1994. The newspaper covered cultural and political events in Miguel Pereira and other municipalities in south central Rio de Janeiro state. In municipal elections in 2012, Panorama Regional openly supported candidate André Português for mayor of Miguel Pereira. However, the person who won those elections and became mayor was Cláudio Valente, whom the newspaper “severely criticized” for alleged mismanagement and corruption, according to the report by A Safer World For The Truth.

That report analyzed editions of Panorama Regional between June 2013 and February 2014. According to the report, criticism of Miguel Pereira's city hall and investigations into irregularities concerning bids for cultural events in the city that were published in the newspaper during this period stood out.

Bartman said that Palma was “an information activist, in a way.” Days before he was murdered, he sent requests for access to public information about city hall finances and bids related to the city's carnival festivities.

“These are dangerous moves [for local journalists], because it really means they are trying to get skeletons out of the closet, really trying to find proof, real evidence of power abuse and corruption,” Bartman said.

On Feb. 13, 2014, Palma was arriving home when two men passed him on a motorcycle. The man on the back got off the motorcycle, approached Palma and shot him three times. He died at the scene. The man driving the motorcycle turned around, the shooter got on the back and the two fled. The scene was recorded by security cameras at Palma's home and the images were released by the police in April 2014.

Palma’s murder occurred after at least two years of the journalist being threatened for his work. Some of those threats were reported by the journalist to the police, as stated by his family at the time of his death.

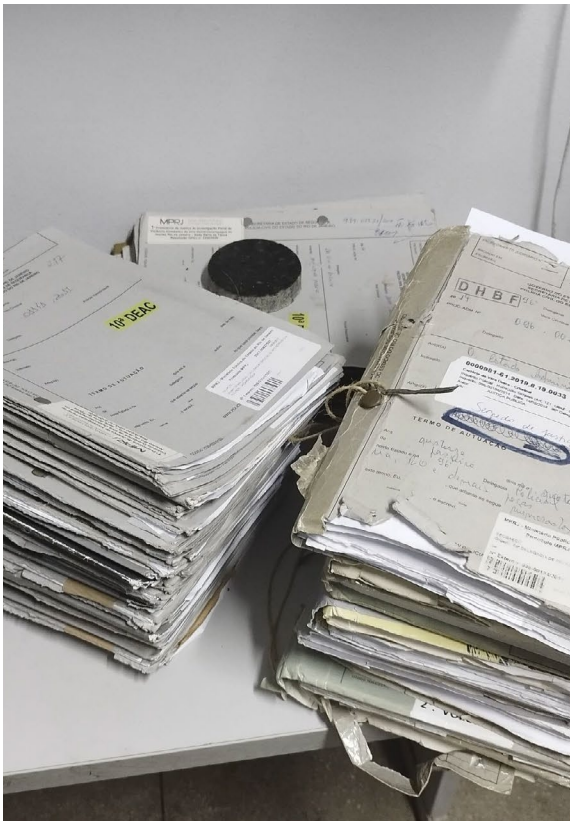

Police files of Pedro Palma's murder investigation. (Courtesy / A Safer World for the Truth)

Initially, the investigation was carried out by the 96th Police Department of Miguel Pereira. A month after the crime, it was passed on to the Baixada Fluminense Homicide Division, in the municipality of Belford Roxo, at the request of the Rio de Janeiro public prosecutor’s office. Eight years later, in June 2022, the case was sent to the 10th Notary Collection Police Station, a unit responsible for “concluding investigative procedures.”

The report from A Safer World For The Truth on Palma's case concluded that there were “excessive and undue delays at crucial stages in the official investigation (...) due to the sluggish communication and unwillingness to act by those within the criminal justice system.” Also according to the report, “the homicide division in charge of the case repeatedly neglected requests from the [public prosecutor’s office] for investigative actions to be undertaken.”

Furthermore, telephone data that could have been analyzed to identify suspects allegedly ended up lost during the investigation. According to the report, a police officer from the homicide division said he was unable to find the data sent by telephone operators. And the agents who received judicial authorization to analyze this data in 2017 – three years after Palma's murder – no longer work at the division.

“That's a big issue that made sure that the investigation was not concluded and no one was prosecuted,” Bartman said.

A man named as a suspect in Palma's murder was arrested in June 2014 in Rio de Janeiro. According to the report from A Safer World for the Truth, this man was not charged with the crime and it is not known what happened to him after his arrest. LJR attempted to contact the Rio de Janeiro Civil Police by email and telephone to obtain more information, but did not receive a response by the time this report was written.

The initiative A Safer World for the Truth also criticized the lack of transparency in the investigation, on which judicial secrecy was imposed from the beginning. This prevented Palma's family members from accessing the case and from being able to “exercise their legal right to propose that additional evidence be collected or witnesses heard, and to scrutinize the investigation to prevent misappropriation of evidence,” according to the report.

Palma's widow was only able to access the investigation files from police in 2022, and only after going to court requesting her right to have access to the developments of the case to find out what had been done so far. Bartman said that it was through her that the team at A Safer World for the Truth was able to analyze the official investigation. According to the report, the police investigation into Palma's murder consists of three volumes and around 500 pages in all, and another five books with thousands of pages of attachments.

Angelina Nunes, coordinator of the Tim Lopes Program of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji), collaborated with the international initiative in investigating the Palma case. She was in Miguel Pereira and interviewed Palma's family and friends, as well as witnesses to the murder, police officers and judicial operators who worked on the case. Nunes told LJR that, so many years after the crime, people in the city are still afraid to talk about what happened. She also pointed out the turnover among the people responsible for the case at the public prosecutor’s office, contributing to the slowness of justice and impunity for this crime.

“When I spoke to the prosecutor responsible for the case a year or so ago, before we produced the report, he said: ‘in six months I will conclude the case.’ Six months later, I called him, and he was no longer [the case prosecutor], it was someone else. So every time the prosecutor who is handling the case changes, [their work] practically starts over from scratch,” she said.

LJR contacted the public prosecutor’s office to obtain more information about the current status of the Palma case.

“Investigations are ongoing. It is not possible to provide further information due to the decreed secrecy,” a spokesperson replied.

Although Palma's murder has yet to be solved, the investigation into the case led to at least three major police operations between 2015 and 2016 to disrupt alleged corruption schemes in the local governments of Miguel Pereira and at least seven other municipalities in the region. These operations were based on Palma's work as well as clues that emerged when investigating the journalist's murder.

For Nunes, the operations ended up overshadowing the investigations into Palma's murder.

“These operations gained volume, gained strength, because [the alleged corruption schemes] involved mayors, secretaries, many authorities. It was absurd corruption, so [the operations involved] the public prosecutor, Federal Police, Civil Police… But the murder [of Palma] ended up not being forgotten, but left aside because other things to investigate emerged,” she said.

For Bartman, these operations made visible the fact that not only the public, but also “democratic institutions were dependent on information from Pedro Palma.”

“Because of Pedro Palma's reporting and also eventually his murder, the [public prosecutor’s office] started large-scale corruption investigations that actually have received much greater attention than the murder of Pedro Palma himself,” he said. “These institutions, even the Judiciary, become visually impaired in a way if these [local investigative] journalists stop doing their work. With someone like that being killed, other institutions have much less capacity, actually, to do their work and start investigations. Even lawyers and prosecutors read newspapers and directly depend on journalistic information.”

In April, when the report from A Safer World for the Truth was published, Bartman and other co-authors of the document presented their analysis to the public prosecutor’s office. According to him, the people responsible for the case welcomed the contribution. The office committed to searching for phone data allegedly lost by police and has since interviewed new witnesses, Bartman said.

According to CPJ, in 12 of the 44 cases of journalists murdered in Brazil since 1992 there is “partial impunity,” that is, some suspects were convicted of the crimes, but not all. Only six cases received “full justice,” in the CPJ classification, with perpetrators and masterminds held responsible for the crimes.

Nunes noted that the complete impunity in Palma's case, with no suspect identified, is “cruel” to the journalist's family, who continue to follow the case and fight for justice.

“The family is in suspense. What exactly happened? Who ordered the killing? Why did he die? ‘Ah, those two boys on the motorbike were the ones who killed them.’ Yes, who are these people? Who hired these people? It wasn't a robbery, it didn't have the characteristics of a robbery. And he had already received threats. So it’s very cruel, the family is in suspense all the time,” she said.

Impunity is also “fuel” for other crimes, Nunes said.

“If this case goes unpunished, if there is no outcome, this will only generate more violence. Impunity is a fuel for more crimes, because the people who commit or who order, the people in charge, are completely sure that nothing will happen,” she said.

She also pointed out the impact of impunity on other journalists in the region, who may self-censor to protect themselves.

“If they killed [Pedro Palma] and nothing came of it, why should I, who have a tiny media outlet, or who am a freelancer, get involved in this story? Why am I going to make reports and investigate some things?” she asked. “This also ends up serving as fuel to discourage many other journalists, so they change the way they work for fear of suffering reprisals, because they know they will go unpunished.”