Melissa Alfaro Méndez was 23 years old and worked as head of news for Peruvian magazine Cambio. It was 1991 and Alberto Fujimori had been president for just over a year. The country was already seeing signs of how his extreme anti-terrorism policy would take form.

Cambio, considered an opposition magazine, frequently denounced human rights violations at the hands of the government, which even led to it being accused of being as an ally of the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA, for its acronym in Spanish).

On Oct. 10, 1991, an envelope arrived at the Cambio newsroom addressed to director Carlos Arroyo. As part of her duties, Alfaro opened the envelope, which was unfortunately loaded with ANFO gelatin, a complex explosive used only by the Peruvian Army. She died at the scene.

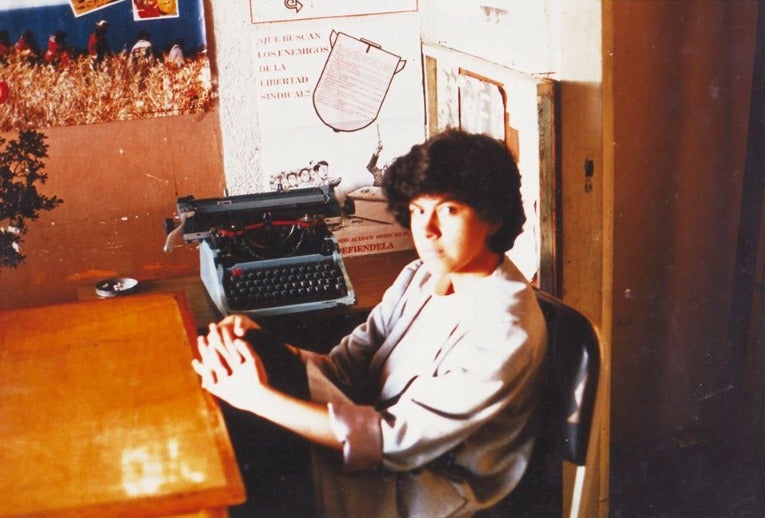

Peruvian journalist Melissa Alfaro. (Photo: Melissa's family courtesy)

Her family has been fighting for justice for 33 years. When they thought the trial would finally begin in 2019, the COVID pandemic halted their hopes. Finally, on March 21, 2023, the trial formally began against three alleged “indirect perpetrators”: Vladimiro Montesinos, Fujimori's former advisor and de facto head of the National Intelligence Service (SIN); Julio Salazar Monroe, former official head of the SIN; and Pedro Villanueva Valdivia, former commander-in-chief of the Army. Víctor José Penas Sandoval, former intelligence agent and retired captain of the National Police, was also charged as alleged material perpetrator of the crime.

The case is currently in the oral trial stage and could take at least four more months, Gloria Cano, head of the legal team of the Association for Human Rights (Aprodeh) and the lawyer representing Alfaro's family, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Despite the slow progress, the murder could remain unpunished due to the Amnesty Law recently enacted by President Dina Boluarte on Aug. 13.

The law grants a general amnesty to members of the armed forces, police and self-defense committees (civilian groups formed by the military to combat subversion) accused or investigated for crimes committed during the country's internal armed conflict (1980–2000). It also mandates the release of individuals convicted of these crimes who are over 70 years of age.

“Ever since [the Amnesty Law] was proposed as a possibility, we've begun to fight against it,” Norma Méndez, Melisa's mother, told LJR. “Our hopes have been dashed after fighting so hard for the trial to move forward, for it to even begin. We had to fight a lot, and with this Amnesty Law, we don't know what's really going to happen.”

The law caused alarm from the beginning of its discussion in Congress and has been rejected by national and international organizations. It was promoted by the Fuerza Popular party, led by Keiko Fujimori, daughter of deceased President Fujimori, who was convicted of human rights and corruption offenses. It was pushed forward by congressmen like former Minister of the Interior Fernando Rospigliosi and also had the support of retired Admiral Jorge Montoya.

Supporters of the law argue it moves the country forward from a time of bloody conflict, is a tribute to those who fought terrorism and is a remedy for cases that have taken decades to try.

Yet, critics worry about what it means for justice for families of human rights abuse victims.

“For us, this is a law that not only violates victims' right to access to justice, but also disobeys the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court [of Human Rights], which says that the State cannot impose obstacles preventing a judicial solution for victims,” Cano said. “What the Amnesty Law does is disobey its mandate to investigate, prosecute and punish human rights violators.”

When the law was still being debated in Congress, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) urged Peru to "refrain from passing amnesties for serious human rights violations.”

In a Sept. 3 decision, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (I/A Court HR) upheld the immediate suspension of the Amnesty Law. This recent decision upholds the July 24 ruling ordering Peru to "immediately suspend processing of the bill [...] and, if it is not suspended, the competent authorities shall refrain from enforcing this law, so that it has no legal effect."

President Boluarte has said the court is trying to interfere with Peru’s sovereignty.

Alfaro’s case isn’t the only one in jeopardy, according to legal experts and press advocates.

When Daniel Urresti, former Minister of the Interior and retired Army general, was sentenced to 12 years in prison on April 13, 2023, as a co-author of the murder of journalist Hugo Bustíos, the ruling was considered historic. Not only because of the sentencing of a high-ranking official, but also because Bustíos's case became the first, and so far the only, to achieve full justice: the entire criminal network had been convicted.

Something "historic" also happened when, on Sept. 30, 2024, Alberto Rivero Valdeavellano, a former high-ranking military official, was convicted for the forced disappearance of journalist Jaime Ayala Sulca in 1984. Another former military official implicated in the case, Augusto Gabilondo García del Barco, former head of a counter-subversive base, is in Spain and his extradition is pending, Juan José Quispe, a lawyer representing Ayala Sulca's family, told LJR.

These important sentences, however, could be affected by the Amnesty Law.

In the case of the murder of Bustíos, the sentence against Urresti is final following ratification by the Supreme Court. However, given that the former military official is approaching 70 years of age, he could be released, Qusipe said. Urresti's defense team has already requested that his sentence be annulled under another controversial piece of legislation, the so-called “Impunity Law," which does not prosecute crimes against humanity committed before July 1, 2002.

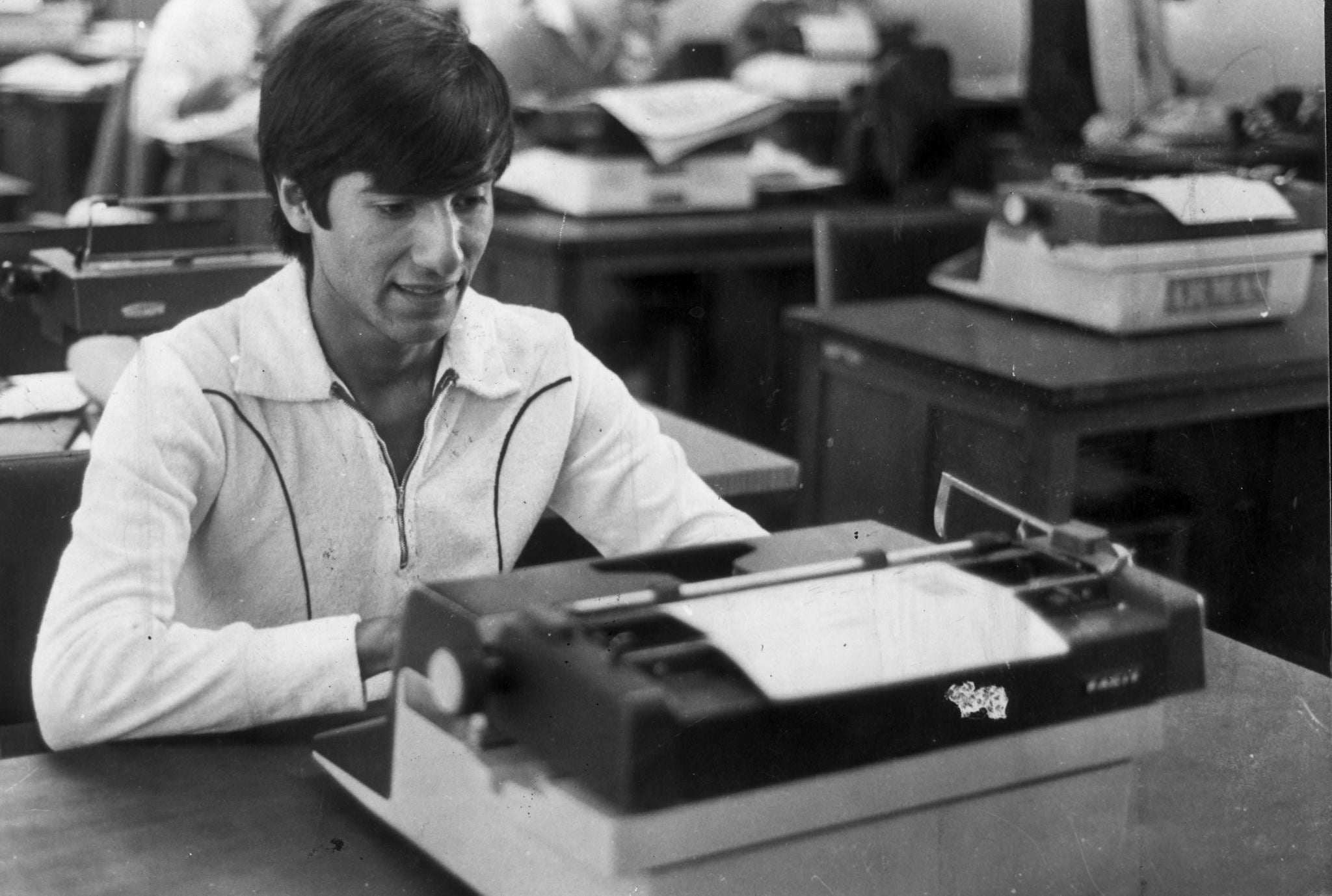

Peruvian journalists Jaime Ayala Sulca disappeared in 1984 during the armed conflict. (Photo: From Facebook page Justicia para Jaime Ayala Sulca)

In the case of Ayala’s disappearance, due to García del Barco's age, his extradition process could also be truncated, the lawyer added.

There are still more cases of violence against journalists from the internal armed conflict. Journalists Pedro Yauri and Hilario Ayuque, along with Ayala Sulca, are the three journalists who disappeared during that period.The investigations into their cases could also be affected, Zuliana Laínez, president of the National Association of Journalists of Peru (ANP), told LJR.

"At the ANP, we have been absolutely firm in rejecting this law, not only because of what it represents for the country—remember that this country has more than 25,000 missing persons, according to official figures—but also because it directly affects several cases of murdered and disappeared journalists," Laínez said.

Laínez emphasized that in addition to the missing journalists, more than 50 journalists were murdered between 1980 and 2000.

Lawyers Cano and Quispe agree that the only solution for now is for Peruvian judges to disregard the law.

"All judges in the Republic are obligated to apply what is known as diffuse control or constitutional control. That is, judges must determine whether the law violates the State's Political Constitution," Quispe said.

Likewise, Quispe said, there is also an "international obligation" to apply conventional control. That is, since the Peruvian State ratified the American Convention on Human Rights and accepted the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, it is obligated to comply with its rulings.

"If a law from a State that is party to the administrative jurisdiction goes against the rulings of the Inter-American Court, they will prefer the rulings of the Inter-American Court to the law of a State party. That is conventional control," Quispe said.

In fact, in a case unrelated to journalism, Judge Richard Concepción Carhuancho has already disregarded the application of the controversial "Impunity Law.” Because of this decision, he faces a complaint for alleged malfeasance before the National Justice Board filed by congressman Rospiglosi.

The Puno Bar Association of Peru demanded the Amnesty Law's repeal due to its violations of international obligations and called on judges to disregard it. In an analysis, the Foundation for Due Process established that the law "lacks legal effect" because it fails the conventionality test, and that the judges' response would be to disregard it.

For now, Melissa Alfaro's family will continue participating in the Thursday protests in front of the Palace of Justice.

“I hope the judges disregard the law. We have that hope,” Alfaro’s mother said.. “We don’t know how the government will proceed; right now, it’s completely against us, the family members [...] we can’t understand such an inhumane woman who can’t think more highly of her people.”