It took 40 years for the family of Peruvian journalist Jaime Boris Ayala Sulca to feel they were getting some kind of justice in his forced disappearance. After a two-year trial, a verdict could be delivered by September against the two military officers accused in the crime.

But a new law approved by congress this month could nullify Ayala Sulca’s and many other cases of crimes against humanity committed before 2002 by military officials and terrorist groups.

Varios medios cubrieron la desaparición del periodista Jaime Ayala. Desde el primer día, su esposa Rosa Luz Pallqui luchó por la verdad y justicia. En la imagen, un artículo que apareció en el periódico La República. (Ministerio de Cultura - Centro de Documentación e Investigación)

“I have fought for 40 years for access to justice since the moment my husband was detained by the marines,” Rosa Luz Pallqui, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “Unfortunately, justice took too long to judge those responsible.”

Ayala Sulca went missing during one of the most violent periods of Peru’s armed conflict, marked by actions from the guerrilla group Shining Path and the government’s extreme measures to contain them. In 1983, the government established a political-military command in the province of Huanta, Ayacucho, to control the actions of this group.

As part of their operations, the Peruvian Naval Infantry set up their headquarters in the municipal stadium of Huanta. Years later, investigations by the Public Prosecutor's Office and reports from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), identified the stadium as a clandestine detention and torture center.

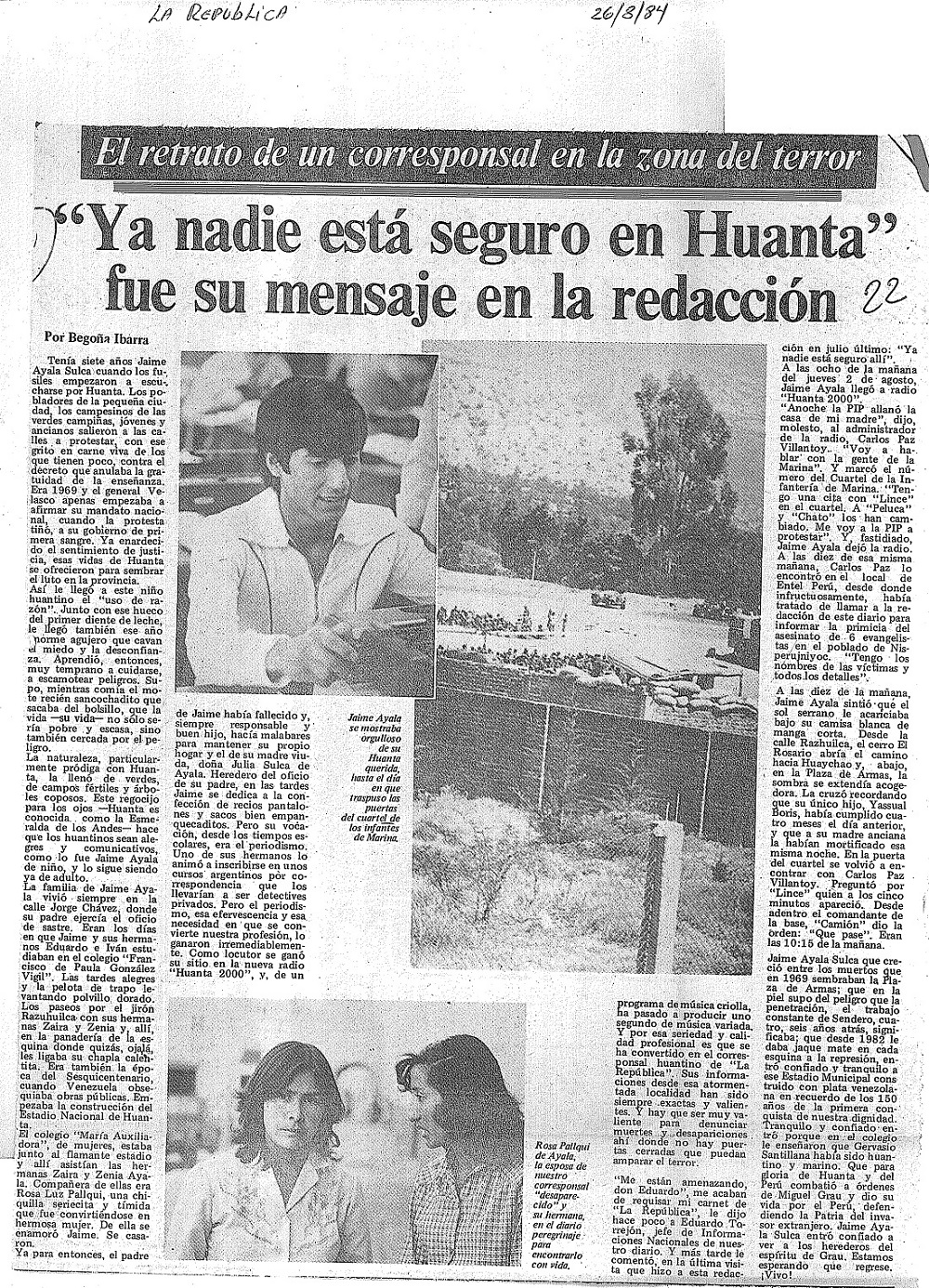

Ayala Sulca, 22 years old, had a journalism program on Radio Huanta 2000 and was a correspondent for the newspaper La República. He covered topics ranging from the Shining Path's actions to human rights violations by the armed forces.

On Aug. 2, 1984, Ayala Sulca went to the military headquarters at the stadium to file a complaint about a raid on his mother’s home the previous day and beatings his brother had received from military officials. Several witnesses who spoke with the prosecutor's office and the truth commission reported seeing the journalist enter the stadium, but they never saw him leave.

Pallqui, Ayala Sulca’s wife, first demanded the release of her husband, and over time, she called for the punishment of those responsible for his disappearance. Finally, she asked for the return of her husband’s body to “give him a Christian burial.” None of these demands have been met.

Pallqui also suffered the disappearance of her father and death threats against her and her son, who was 4 months old when his father went missing. They fled from Huanta to Lima, and years later, when investigations into Ayala Sulca's disappearance resumed, her son continued to receive threats and fled Peru.

“I did not receive any support from the state, nor from any institution,” Pallqui said. “It was a very difficult time for me.”

Ayala Sulca’s disappearance is part of what became known as the “Huanta 84 Case,” the family’s lawyer, Juan José Quispe, explained to LJR. The Huanta 84 Case also includes the murder of six members of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Callqui and the discovery of the Pucayacu graves containing 50 bodies.

These events took place in August 1984 in Huanta and, according to the truth commission, members of the Navy were responsible. In the first investigation opened by the prosecutor’s office that year, the officer in charge of the Navy detachment, Álvaro Artaza Adrianzén, known as “Commander Truck,” and the officer from La Mar, Román Martínez Heredia, were implicated.

Memorial para el periodista peruano Jaime Ayala. (Foto: Tomada de la página de Facebook Justicia para Jaime Ayala Sulca)

This investigation was later shelved and reopened when the truth commission handed the case to the prosecutor’s office as one of the cases considered prosecutable in 2003. This new investigation established the chain of command to determine responsibilities, Quispe said.

According to the truth commission report, Jaime Ayala “was a victim of forced disappearance, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and arbitrary execution by members of the Navy.”

Two officials are being tried in the case: Alberto Rivera Valdevellano, former head of the Political-Military Command of Huanta and La Mar, and Augusto Gavilondo García del Barco, former head of the counter-subversive base of Huanta, who is currently in Spain awaiting extradition. The prosecutor’s office requested they both be sentenced to 25 years in prison. Regarding Artaza Adrianzén, the latest information indicated that he was dead, although his body was never found, and the whereabouts of Martínez Heredia are unknown.

“With 62 victims, over 150 witnesses, and expert testimonies, it was bound to be a very lengthy investigation,” Quispe said.

Human rights observers and Ayala Sulca’s family members are now concerned about a request from the defense to apply Law 32107, popularly known as the "Impunity Law." Enacted by Congress on Aug. 9, the law allows for a statute of limitations for crimes against humanity committed by terrorist groups and military personnel before July 1, 2002.

If the judge grants the request, Quispe said, the case would be closed.

For Zuliana Lainez, president of the country’s National Association of Journalists (ANP), the precedent set by this decision is highly concerning, as this is the first case in which this law is being invoked. She told LJR that there are at least three trials involving violence against journalists that occurred almost 40 years ago and that could be completely closed under this law. In fact, the case of the 1988 murder of journalist Hugo Bustíos, the first crime against a journalist to see absolute justice, could be affected.

Additionally, the ANP has records of at least 54 journalists killed between 1980 and 2000, some of whom may no longer be investigated.

Perfil hecho al periodista peruano Jaime Ayala por el diario La República. (Ministerio de Cultura - Centro de Documentación e Investigación)

“This is a law tailor-made to absolve all those involved as perpetrators of crimes between 1980 and 2000. That’s the risk,” said Lainez, who pointed out that some congressmen are former military and naval officers.

However, she trusts that justice will prioritize other agreements and treaties signed by Peru, as well as calls from various organizations highlighting the unconstitutionality of the law. Quispe shares this belief, suggesting that it might be feasible for the judge to prioritize decisions from Peru’s Supreme Court or the American Convention on Human Rights, which establishes the non-applicability of the statute of limitations for crimes against humanity.

For Rosa Luz Pallqui and her son, the approval of this law was one of the hardest blows.

“It is a law of impunity and not a punishment for the murderers of my husband and hundreds of victims who were detained and tortured in military bases,” Pallqui said.

The next hearing in this case is scheduled for Aug. 23. During it, the judge could determine if the new law applies, Quispe said.