When you talk about Colombian magazine Semana you're not only talking about one of the most recognized media outlets in the country, but also one of the most prestigious. Its history, since it was re-founded in 1982 by Felipe López, has been characterized by major journalistic investigations that have gone beyond scandals causing concrete actions by authorities, and by prestigious columnists who have had strong impact on public opinion and spoken directly to the country's leaders.

For that reason, the resignation of at least 16 journalists on November 10 had a national repercussion. Among the most striking resignations were those of Ricardo Calderón, its newly appointed director and author of the most iconic of Semana's investigations, as well as that of renowned columnists such as María Jimena Duzán and Antonio Caballero, illustrator Vladdo, managing editor Mauricio Sáenz, editorial director Ricardo Pardo and president of Publicaciones Semanas Alejandro Santos.

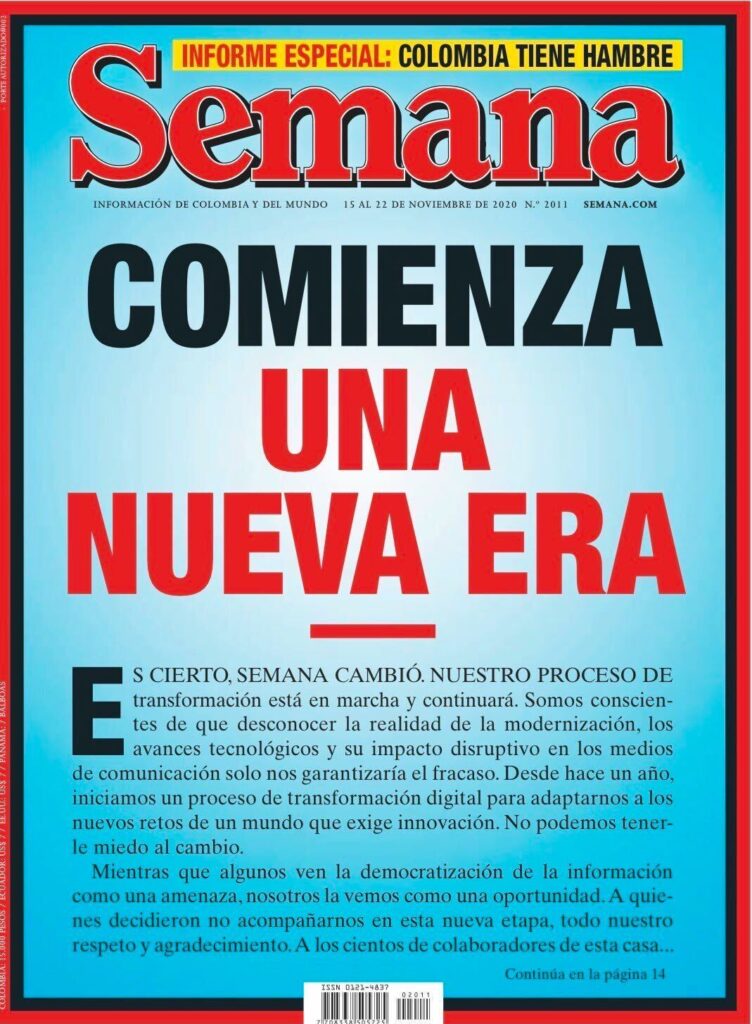

Cover of the first Semana magazine after its acquisition by the Gilinski family.

The feeling among journalists and readers was that the traditional Semana was dying, and that it would soon become a media outlet not only closer to the government, but also one with a tendency towards digital viralization, avoiding investigative reporting. The situation also raised concerns about how it affects the general media ecosystem in the country and what would happen to its audience.

Two media experts shared their findings in an interview with the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

“[The situation] is very serious," Germán Rey, professor and researcher at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and instructor at the Gabo Foundation, told LJR. “Semana was a magazine with great tradition in Colombia because of its journalistic criteria, because of the investigations it carried out, because of the impact [those investigations] had on public opinion in the country, because of the topics it covered with an important journalistic quality. In this sense, we lost an approach to Colombian issues that I would consider absolutely necessary.”

For Rey, the situation of Semana has several worrisome elements that it shares with other countries in the region, such as the media crisis. An economic crisis that before the recent resignations had been evidenced by layoffs, the shutdown of some of magazines that belonged to the group, “the layoff of Daniel Coronell, possibly the most important of its investigative columnists, and that ends in this first phase with the sale of the magazine to the Gilinski family,” he said.

The acquisition of the magazine by “one of the richest families in Colombia,” confirmed on November 10, is considered by Rey one of the special characteristics of the Semana case. Firstly, because, with this purchase, “the media landscape of Colombia is fundamentally in the hands of large economic family groups that have interests in public tenders, infrastructure, banking, the media, as you know.”

On the other hand, in Rey's view, the opinion of the new owner “who wants to turn Semana magazine into a Colombian FOX, into a Creole FOX, is also worrisome. This already determines the direction the media outlet will have in the future,” he explained.

However, Rey also believes that the change in the magazine has a hint of retaliation for the investigations published in the last two years that would account for acts of corruption and abuses within the Army, as well as reports on social protest, the peace process and even investigations on former president Álvaro Uribe.

“All these reports generated a lot of resistance, fears and I understand that what is happening in Semana magazine is in some way a retaliation of certain political movements and power movements in the face of accountability reporting, [in the face of] a kind of journalism that is based on investigation and a kind of journalism that has an open and pluralistic opinion,” said Rey.

Ricardo Calderón was the director of the magazine for almost two months before his resignation. He recently received awards such as the Rey de España and the Maria Moors Cabot. (Photo: Courtesy)

The changes are also oriented toward the search for greater profitability, which is not necessarily a problem in itself. In fact, for Rey, the healthy economic life of the media is necessary even for public opinion.

“But what you need to ask yourself is what is the concept of profitability. With what type of journalism is this profitability made? Is it journalism that seeks to capture an audience, is it sensationalist journalism, is it journalism attached to a political perspective, another right-wing political project, is it journalism that uses the polarization that the country is experiencing in order to be profitable? It is profitable journalism that supposedly made new wine in old wineskins. This is how I would define Mr. Gilinski's proposal,” said Rey.

This search for profitability based on virality and likes is also identified by Víctor García Perdomo, director of the master's degree in digital communication at the University of La Sabana. He said to LJR the magazine will soon notice that the business model based on clicks and views “is not going to be enough to sustain itself in the future.”

“A magazine like Semana that has had important investigations and that is a traditional media outlet will have to find a space in which it reaffirms, as other media have done, the very quality of content," said García. “Among other things, [that is] because online advertising is increasingly placed on large digital platforms. Facebook, Google, YouTube are taking the majority of the advertising money and the traditional media are finding that the business model through subscriptions or through advertising is not sustainable over time. They increasingly depend on subscribers or niche audiences to pay for content and those audiences only gain loyalty through very good quality content, as The New York Times has shown.”

On the cover of the June 15 issue, the first since the massive resignation and since the magazine became the exclusive property of the Gilinksi family, it was announced that a new era had begun and that the shift towards digitization was necessary. “To those who decided not to join us in this new stage, all our respect and gratitude,” said the editorial.

Gabriel Gilinski, the current owner of the magazine, told Spanish newspaper El País that the unification of the print and digital newsrooms has likely generated unrest within the magazine, but that this change was inevitable. However, he said that the magazine will continue to make quality journalism.

“Semana will continue to carry out long-term investigations,” Gilinski told El País. “Why aren't we given the opportunity to show that the new model works and that it will be balanced?”

“When Gilinski talks about giving time to this journalism, I, having followed the process, think that what he hopes for is that likes will increase, users will increase, the audience on platforms will increase and because of that he can increase the profitability of the media outlet that he acquired,” said Rey.

For Rey, the alleged tension between the newsrooms of the print magazine and the digital one is not a convincing explanation.

“The tensions were due to different forms of journalism, different ways of understanding the country and of relating to the country's issues,” he said. “That is where the center of the problem is and, of course, that center of the problem, the problems of Semana magazine, has very serious implications in the understandings of the problems that Colombia has been experiencing for years.”

Opportunity for digital natives

According to García Perdomo, if the audience starts to move away from Semana, Colombia's media landscape is basically one where digital native media and even traditional media, like El Espectador, could have a chance. For him, the departure of renowned journalists and columnists can be used by others to “reinforce” their newsrooms.

In fact, when Daniel Coronell and Daniel Samper Ospina left Semana last June, they created the column website Los Danieles. Both Daniels were joined by Samper Ospina's father, Daniel Samper Pizano - a renowned columnist who was retired - and recently by Antonio Caballero, who resigned from Semana in the last wave. María Jimena Duzán, another renowned columnist who left Semana, now has a segment on the radio station La W.

“Diversification of the offer will come,” said García Perdomo. “Generally what we see in Latin America is that traditional journalists who suffer from this transition try to search, specifically in online spaces, to generate products or projects that have a lot of quality and that are opposite to that desperate search for clicks or that desperate search to generate audience and volume,” he assured.

Native digital media such as Primera Página, on economic issues; La Silla Vacía, on political issues; and even content aggregators like Pulzo, could attract the audience that decides to stay away from Semana.

Rey agrees that professional digital media - as he categorizes media outlets created by professional journalists - will be able to count on Semana's most critical audience, which would also include Cuestión Pública y Vorágine.

However, it is not a question of taking the place of Semana because digital native media outlets do not have the infrastructure to do so, as was said in Presunto Podcast's episode in which they analyzed the case. According to María Paula Martínez, the situation in Semana will have an effect on “freedom of expression” because it is about the change of an important media outlet. Sara Trejos, in that same episode, also pointed out that it would take hundreds of issues of a native digital media outlet to match an issue of Semana.

This is similar to what Rey believes: Before the media ecosystem improves, the situation for them and for the country's information will get worse.

“There is still a lot to get worse,” Rey said. “My diagnosis is very simple: the situation will get worse, the situation in some cases will become more dramatic, the reductions in newsrooms will increase. But in the meantime, there are other styles of journalism that are growing and in the meantime - I would hope, I may be naive and optimistic - society should consider that quality journalism is required. […] We need a kind of journalism where truthfulness reigns, where investigation reigns, where rigor reigns, where public interest reigns. Nothing less than that is what is at play right now.”

*This story was originally written in Spanish and was translated by Erica Alves and Erica Mancha.