Mexican journalist Miroslava Breach was assassinated due to her journalistic investigations, ruled the federal judge Nelson Pedraza, who issued on Aug. 21 a 50-year prison sentence for one of the material co-perpetrators of the murder, Juan Carlos Moreno Ochoa.

Miroslava Breach. (Photo: Facebook)

The court ruling is emblematic, as pointed out by the Mexican organization Propuesta Cívica, which is representing the Breach family and the international organization Reporters Without Borders, for becoming the first murder trial of a female journalist litigated at a federal level and which had a sentence in Mexico.

“The sentence against Juan Carlos Moreno Ochoa, known as ‘El Larry,’ and who is known in the region as the boss of hitmen of the Salazar group, represented a firm step in this country, in which there is a 99.7% impunity in homicides against journalists,” Mexican journalist, Breach’s friend and colleague Patricia Mayorga told LatAm Journalism Review. “But we are speaking about only one person in the criminal structure that evidently was behind Miroslava’s homicide and the structure continues intact and there is still a lot that needs to be done,” she added.

Almost three years after the trial started for Breach’s murder, Moreno Ochoa was declared guilty on March 18 and sentenced on August 2020. In this judicial process, there is an arrest warrant for Jaciel Vega Villa, who has been pointed out as another perpetrator and who is a fugitive.

Breach was killed in her hometown, Chihuahua, after being shot eight times on the morning of March 23, 2017. She was in her car waiting for her son to take him to school.

Facing the lack of support from authorities and the lack of collective conscience of Mexican society about the importance of investigative journalism in the country, Mayorga said, the support and solidarity of the Mexican journalism industry and international organizations have been important in the first steps and resolution of the trial of Breach’s killing.

“I think that this external support helps us to pause to have a strategy and to advance with more clarity… It means not feeling alone while you are reporting, in your job in a corner of a small town, which is [the experience] we live, not only Miroslava and I, but thousands of journalists in the country, and that gives us a lot of strength,” Mayorga said.

Miroslava Project and 23 de Marzo Collective

After Breach’s murder, and the irregularities and delays in the judicial investigation of her death, the Proyecto Miroslava (Miroslava Project) was born as a Mexican initiative comprised by anonymous journalists from the Colectivo 23 de Marzo (23 of March Collective) and which also has the support from international organizations such as Forbidden Stories, Bellingcat and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLiP).

Colectivo 23 de Marzo, Mexico. (Screenshot)

Up until now, Proyecto Miroslava published three investigative pieces about the loose ends and deficiencies of the investigation by the Attorney General of the State of Chihuahua and the Attorney General of the Republic. The stories are “Unexplored leads in the murder of journalist Miroslava Breach,” “5 other suspicious deaths linked to Miroslava Breach’s murder,” and “The journalist who refused to be complicit.”

These features, which were published simultaneously on Sept. 4, 2019 by more than 20 outlets in Mexico, put great pressure on the authorities, Colombian journalist María Teresa Ronderos, co-founder and director of CLiP, told LJR. “Furthermore, it helped international organizations who went on a mission of freedom of expression, weeks after publishing, as a way to demand the Mexican government for greater results in the investigation of the crimes against journalists.”

Originally, the Attorney General said that the mastermind was Moreno Ochoa, but, Ronderos said, the collective investigation demonstrated that that thesis had many loose ends. “At the trial, the Attorney General categorized him as a co-perpetrator. And the trial confirmed what the investigation [of the Proyecto Miroslava] had said, that politicians were involved,” she pointed out.

Mexican journalist Marcela Turati, colleague of Breach and who was also born in Chihuahua, told LJR that until those who were tried, sentenced, and participated and planned Breach’s death are in jail, Mexican journalists will not be able to feel at peace nor any pride in this sentence.

Turati, founder of the network Periodistas de Pie and the investigative portal and journalistic training Quinto Elemento Lab, pointed out that in Miroslava's case the signs she left in her columns and what she told colleagues, friends and family members about the threats she received were very powerful.

“There is enough evidence that what bothered them was her investigations into narco politics in the Sierra Tarahumara, a place where organized crime has ruled for several years. She notified the [Protection] Mechanism, officials, told her family members, she made it clear that she was being threatened," she said.

According to Ronderos, what is still missing from the ongoing trials are the convictions against the masterminds. She pointed out that the suspicious actions of possible cover-ups and obstructions to the judicial investigation found by the Proyecto Miroslava investigations remain to be clarified.

“Proyecto Miroslava continues to tie up the loose ends of the trial's revelations and its own findings. The transnational alliance of Mexican and foreign journalists also continues,” Ronderos emphasized.

The last investigation in the Sierra Tarahumara, in northern Mexico

Mayorga, correspondent for Revista Proceso, worked very closely with Breach in the features about politics and drug trafficking in the Sierra Tarahumara. She said that, at the beginning, both did not warn about the signs and subtle warning they were receiving at that moment from people in the region about the dangers they faced in investigating those issues. She had to leave Chihuahua after Breach was killed and published her articles anonymously.

“The first threats came after the stories about the candidates and pre-qualified narco candidates of the PRI [Institutional Revolutionary Party]. The threats were intimidation to the Miros family, in Chinipas, and at the same time there was a group of spokespeople, politicians, businessmen [who said] to stop investigating this, you are in danger. In retrospect, you see it as a system that intimidates you or gives you a warning because it comes from people with power, they are from such a broken system in Mexico,” Mayorga expressed.

Mayorga considers that the corrupt political system and its ties to organized crime in the region still continues and has not been dismantled by any kind of justice system. “I do not feel confident nor secure to do the same type of journalism as before, and I have been writing some more social stories, stories about logging, etc., but not as deeply investigated,” she lamented.

The sour taste of half justice and Javier Valdez

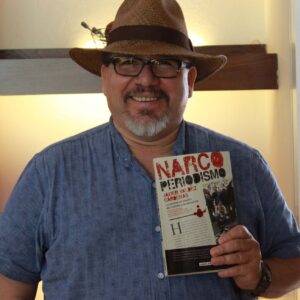

To do journalism in Mexico has an implicit risk, Mexican journalist Alejandro Sicairos told LJR, however, it would be encouraging to be able to do investigative journalism if the attacks on freedom of expression were clarified duly by the government.

Sicairos, co-founder of the weekly investigative journalism outlet Ríodoce and who was a close friend of Javier Valdez, the recognized journalist who was killed by organized crime two months after Breach, said that in Miroslava’s case, he feels that justice continues to be incompletely carried out.

Javier Valdez. (Photo: Facebook)

“And in that despair or in that attitude to file away these types of cases, what ends up happening is that they detain one of the implicated or one of the suspects and all the weight of culpability is set on them and they do not go after the people who were more deeply involved with these types of homicides. We are left with that sour taste in the mouth of institutions that are not fully dedicated to crimes that go against freedom of expression in Mexico,” he pointed out.

In the trial of Valdez’s murder, who was killed at the hands of organized crime on May 15, 2017 in Culiacan, Sinaloa, there is a sentence handed down by a federal judge at the end of February 2020 against one of the perpetrators of the homicide. However, the other person accused during the process continues without a sentence due to postponements, according to the newspaper Noroeste.

Sicairos does not see any political willingness from the current administration, nor of the federal or state authorities to end the impunity of crimes against journalists and against freedom of expression.

According to the 2019 Global Impunity Index of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Mexico is in seventh place within the ranking of 13 countries with the most impunity of crimes against journalists in the world. Since 2000 until May 2020, 159 journalists and media professionals have been killed, according to the National Commission of Human Rights of Mexico (CNDH).

“In Mexico, there isn’t anyone who will stop the trigger, anyone who will stop the hands of any type of criminal. What exists is the sensation [of a bitter taste],” Sicairos said. “And the case of Javier Valdez is a particular example here in Sinaloa that we do not have the necessary constitutional guarantees to do journalism. Not yet,” he concluded.

This story was originally written in Spanish and was translated by Perla Arellano Fraire.