In mid-August 2021, a Brazilian brokerage firm posted a photo of its team on Instagram: around 100 people, all white(and almost all men). In a country in which 54.5 percent of the population is Black, the lack of racial diversity shown in the photo motivated criticism on social networks and even a lawsuit.

A photo populated mostly (or totally) by white people could also be the portrait of many of the great newsrooms in Brazil. In fact, it is the portrait of successive groups of trainees educated by Folha de S.Paulo, as shown in the images that illustrate an article in the newspaper itself about its popular Training Program in Daily Journalism, created in 1988 and which reached its 65th edition in 2021.

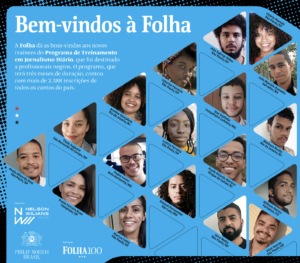

However, in this latest edition of the training program and for the first time in 33 years, the newspaper decided to exclusively select Black professionals. The initiative is part of Folha's efforts to make its newsroom more diverse, Flavia Lima, the newspaper's current diversity editor and coordinator of this edition of the program, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Members of the 2021 Folha training program (Folhapress)

In addition to Folha, Nexo Jornal also launched an exclusive training program for Black people in 2021. These initiatives seek to break down some of the barriers that hinder the entry and permanence of Black journalists in Brazilian newsrooms, also leading to debates about racism and whiteness within organizations.

“The training [program] is Folha de S.Paulo's main new talent selection program,” Lima said. “In all these years, a lot of people who have reached leadership positions at the newspaper have come from these programs. Currently, for example, the two newsroom managing editors (one level below the newsroom director, Sérgio Dávila) have undergone training at Folha. That's why it's important to have a training program aimed at Black people if the goal is to have people of different colors and backgrounds in the newsrooms.”

Flavia Lima of Folha (Courtesy)

According to her, the newspaper recently carried out a census of its employees, and “the portrait that came out of this Folha newsroom was still very essentially white and still a little more male than female.”

“The survey made it clear that Folha is still far from reaching where it aims, which is to have a newsroom that better reflects the society in which we live, that has more plurality and is more democratic,” she said.

“The newsrooms – and I'm not just talking about Folha, but the big newsrooms, of traditional newspapers – are still very homogeneous. The professionals mostly come from the white middle class, with very similar worldviews, habits and routines, and it is inevitable that this ends up being reflected in the coverage that is done, where you look, what we think is relevant,” she said.

Folha's training program aimed at Black professionals received nearly 2,400 applications, the equivalent of 133 candidates per vacancy. Eighteen people (11 men and seven women) were selected and took online classes at night for three months with newspaper professionals and guests. They also produced a special booklet with the theme of Afrofuturism, published in the Aug. 2 edition of Folha.

One of the main objectives of the program, according to its coordinator, was to “absorb” the professionals in Folha's newsroom. Of the 18 people who took the course, one was already working at the newspaper, 12 were hired and two are “in the process of” being hired, while another three are working in other organizations, she said.

“I see a lot of possibility, a lot of potential in this. I think Folha did very well by doing this and can gain a lot from these new visions.”

According to her, Folha's training program aimed exclusively at Black professionals will be carried out annually by the newspaper.

"I think the first step has been taken, which is to recognize that there is an issue and be willing to face it, knowing that the solution will not come overnight, that it is a process, that deconstructing something so deeply rooted will take some time,” Lima said. “I have 20 years of journalism and I've never seen it before. So, this makes me very hopeful that we can have more democratic newsrooms and journalistic coverage, that journalism can become more democratic itself, can better reflect our problems as a society, our different perceptions, different voices, or that is, that the debate can be held including many more people.”

Training for Nexo students

Like Folha, digital native media outlet Nexo Jornal also launched a training program aimed exclusively at Black people this year. The Racial Diversity in Communication Program selected 10 Black journalism students across the country, who will meet three times a week over 10 months to attend online classes in journalistic practices and English.

“Any affirmative action strategy in Brazil has, first of all, a character of historic reparation,” Paula Miraglia, co-founder and general director of Nexo, told LJR. “Brazil is a racist country, a country where racism still plays a very important role in shaping social relations and opportunities. So, we need to think of programs like this and many others as a policy of historic reparation, and these policies are absolutely necessary.”

The program, which was supposed to be in person, ended up being adapted to the virtual environment after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For Miraglia, this turned out to be positive, as it was possible to open the program to people from all over the country, and in the end students were selected from the North and Northeast regions, as well as the Southeast, where the Nexo newsroom is located, in São Paulo.

“We have the opportunity to discuss, to interact, to think about journalism based on different realities, and this greatly enriches the entire process,” she said.

Group of trainees at Nexo (Courtesy Camila Silva)

The intention is to prepare students to work in any newsroom, not just Nexo.

“We created a program so that no newsroom can say no [to these professionals],” Camila Silva, program coordinator, explained to LJR. "Because what exists are several steps and several things basically programmed so that certain people do not access certain spaces, such as newsrooms."

Such barriers would be, for example, the requirement of impeccable text and proficiency in English, including for interns. Many newsrooms, Silva said, want for an internship “a person with ready-made text, who is already someone who has had the opportunity to work on their writing, who writes all his life, who has fostered education and culture at home, who does not need to work to survive and who did not have to choose between studying English or not in order to survive at home with his family.”

Camila Silva of Nexo (Courtesy)

The Nexo program, therefore, is working with students so they can meet these requirements, even if they don't make much sense, she said.

Another expected effect of the program, which had 348 applications for 10 vacancies, is to “impact the market” and inspire other newsrooms to “do their part,” Silva said.

"When you get to some newsrooms that are very white, people say 'ah, we don't have Black professionals around here because we can't find them.’ We presume that just by putting this project on the street, we are already saying that, in fact, there are, throughout Brazil, students from the North, the Northeast, and very well-qualified graduates who signed up to participate in this process even though it was for students, so this is already an invalid excuse.”

Anti-racist training for white professionals in newsrooms

In 2019, journalist Yasmin Santos presented her work for the conclusion of the journalism program at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, entitled ““Letra preta: a inserção de jornalistas negros no impresso” (Black Letter: The inclusion of Black journalists in print). Santos interviewed 47 Black journalists who work or have worked for print newspapers in Brazil, asking about their experiences in newsrooms. Her research was also shared in an article in the piauí magazine, where she was working at the time.

Santos asked her interviewees how many Black journalist colleagues they had throughout their career: 45 percent of them said they worked with up to five Black colleagues in the newsrooms they had gone through, 19 percent said they had worked with up to 10 Black colleagues and 10.6 percent worked with up to 20 Black colleagues. Nearly 9 percent said they never had a Black colleague.

She also asked if they had a Black boss in the newsrooms where they worked. Only 23 percent said yes, and none of the 47 respondents said they had seen three or more Black people in senior positions throughout their professional careers.

Journalist Yasmin Santos. Courtesy

More than half of the journalists interviewed by Santos (55%) said they had suffered racism in the workplace, both by colleagues and by their bosses.

Santos told LJR that she welcomes the training initiatives exclusive to Black people. However, “it is much easier to invest in these young people and students who are entering and who will occupy junior positions within the company, smaller positions, than thinking about how you can also hire Black professionals as editors, newsroom chiefs and higher positions,” she said.

“I think it's an important step, but it's still a very initial step, because we need to discuss this in a structural way,” she said. "I'm also very concerned about not only the entry, but also the permanence of these professionals, because these newsrooms need to be open, they need to be reflecting on diversity, on racism, in order to welcome these professionals, because Brazilian newsrooms are not yet a welcoming environment for this professional. It is necessary that the newsrooms rethink themselves so that this professional can continue not only within this newsroom, but within this career, so that he can grow within this career.”

This type of reflection is happening in the newsrooms of Folha and Nexo, according to Flavia Lima and Camila Silva.

At Folha, “there is a dialogue that has been going on between the newsroom directors, the newsroom managing editors and journalists, reporters and editors, that diversity is a necessity,” Lima said.

The newspaper “has been promoting seminars, inviting experts to speak to the newsroom, in large meetings that bring together all [the newspaper's] professionals to listen to these experts and understand a little about our problems, the roots of why we are not very plural and how to face this in a more pragmatic and effective way,” she said.

“Obviously, it is important that efforts are not petered out in training, especially so that it does not take us five, 10, 15 years to see these same professionals in leadership positions,” Folha's diversity editor said.

At Nexo, Silva said, “since we started with the program, we felt it was necessary to have a more careful look inside the newsroom, because these people would be the ones who would welcome this group that would be arriving from the diversity program.”

We sought to “bring an educational process into the newsroom,” also inviting people to talk to journalists, such as journalist and writer Bianca Santana, who spoke about journalism and Blackness, and psychologist and researcher Lia Vainer Schucman, who spoke about whiteness and racism.

In addition, according to her, Nexo has been trying to hire more Black professionals.

"We were already thinking that it is not possible to have a white newsroom, mostly white, to receive a program for Black people, because people have to see themselves, they have to feel safe, feel welcomed," Silva said.

Marcelle Chagas, founder and coordinator of the Network of Journalists for Diversity in Communication, also considers the training initiatives for Black people to be valuable, but makes the reservation that they could have been developed longer ago.

"I positively assess that after years of a communication structure with little or no participation of Black and Indigenous people, new narratives are being considered, however, I think there are few actions given the history of journalism in Brazil," she told LJR.

Miraglia said that, although the Nexo program is still in month four of the ten planned, a point that has already become evident is that it is necessary "to think about this issue in a more organized and intentional way.”.

“If we, the media organizations in Brazil, really intend to make a commitment to the diversity of their teams, there needs to be a thoughtful, planned, intentional effort, because this is not something that will happen naturally,” she said. “I see this also as a balance of the program, because we also see the limitations imposed on people's trajectories, who do not necessarily have the same opportunities, not necessarily have the same training paths, so we need to be aware of this, if we really want to transform this reality.”

“Structural problems require structural measures,” Yasmin Santos stressed. "We have to get the whole structure of a newspaper, the entire structure of the press, and think of different fronts, on how we manage to transform this. Not necessarily thinking of an isolated project for the entry of Black professionals or journalism students. This is very important, but what can we do beyond that?”

“If we consider the entrance of 10 Black journalists in the universe of 300, 400 professionals, it is still very little,” she continued. “It is not the obligation of these Black journalists to raise awareness among the 300 white journalists they will have to deal with in the newsroom. So, it is [important] to think about the entry of these professionals, think about their permanence, think about a way that brings the discussion of racism not only to Black people, but also white people, so that they can rethink their behavior, think about whiteness and journalism, how they can act to combat racism.”