Journalist Ángel Gahona was killed in Bluefields, Nicaragua, while he was broadcasting via Facebook Live during protests against Daniel Ortega on April 21, 2018. On June 19, 2016, Elidio Ramos Zárate, a journalist for the newspaper El Sur, died after being shot in the head while covering protests and clashes in the city of Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca state, Mexico.

The cases of Gahona and Ramos are part of the list of 10 reporters killed while covering protests, according to the UNESCO report "Safety of journalists covering protests: Preserving Freedom of the Press During Times of Turmoil,” which is part of the World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development series.

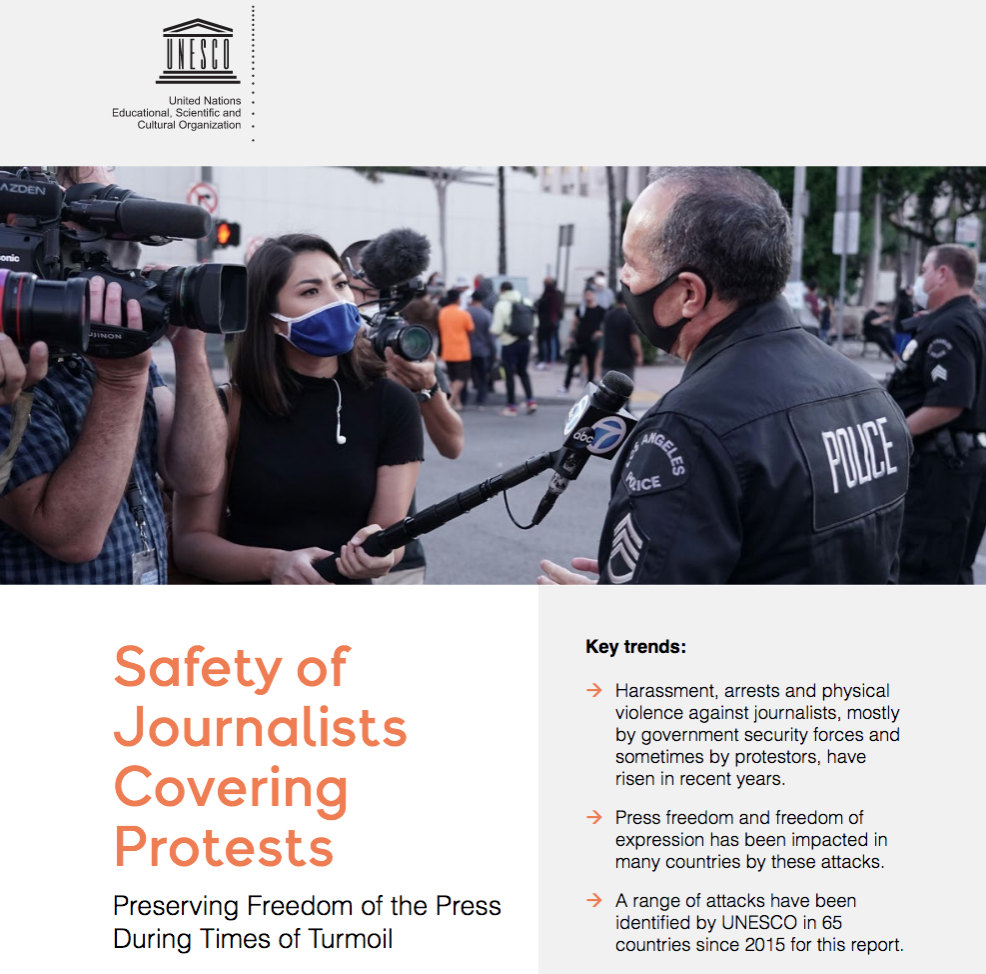

UNESCO's report Safety of Journalists Covering Protests. (Screen shot)

In its report, UNESCO points out the increase in recent years in cases of harassment, detention and physical violence against journalists covering demonstrations. According to their records, from Jan. 1, 2015 to Jan. 30, 2020, at least 125 journalists were attacked while covering protests in 65 countries.

Most of the attacks, according to UNESCO, were the responsibility of members of government security forces, although there are also records of attacks by protesters.

Of the 125 cases, 15 occurred in 2015, 16 in 2016, 21 in 2017, 20 in 2018, 32 in 2019 and 21 in the first half of 2020, “clearly indicating an upward trend in the number of attacks faced by journalists when covering protests.”

The trend seems to hold for the remainder of the year. In Colombia alone, between Sept. 9 and 21, the Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP) recorded 33 violations of press freedom in the context of protest coverage. According to the organization, the attacks against the media and journalists have come from the National Police, in 76 percent of the cases, as well as protesters and unidentified individuals, in 24 percent.

Physical assaults, obstructions of journalistic work, illegal detentions and even threats during coverage were the cases registered by FLIP.

Also in Colombia, in an event that is still being investigated, indigenous communicator Abelardo Liz was wounded by gunshot wounds while covering a protest in the municipality of Corinto, department of Cauca, on Aug. 13 of this year. The communicator died on the way to the hospital.

“Journalists have a double role in covering protests: they are there to guarantee the accountability of the security forces, that is, to inform society as a whole if the actions of these forces were in line with the Democratic State of Law; but they are also there to give voice to the claims of those who protest,” Guilherme Canela, head of the section on Freedom of Expression and Security of Journalists at UNESCO, told LatAm Journalism Review. “Therefore, guaranteeing their safety is, at the same time, an end in itself, since it is to protect the right to freedom of expression and an end to protect another fundamental right, which is the right to protest.”

According to the report, these attacks on the press have violated international laws and norms that have already “been long agreed upon under the umbrella of multilateral institutions.”

In addition to attacks such as beatings, intimidation, surveillance, abduction, arrest, humiliation and destruction of equipment, the report indicates that some public officials used a practice known as “doxxing.” This constitutes publishing private and identifiable information of journalists, which includes their address or names of relatives, "usually with malicious intent." In some cases, print, broadcast or digital media were censored, websites were blocked, and tracking programs were installed on journalists' devices, among other practices.

Although to a lesser extent, protesters also attacked the press, according to the report. Among the practices used by protesters are the temporary occupation of media facilities to take them off the air or to use them to broadcast, temporarily stop them, damage equipment and even set them on fire.

The use of non-lethal weapons against journalists was also highlighted by the report. The document reports, for example, the use of tear gas and rubber bullets in regions such as Latin America, but also pepper balls and butterfly bullets in other regions. In addition to the 10 journalists killed, the use of these weapons left at least 15 journalists seriously injured, according to the report.

Women journalists "were deliberately targeted and attacked because of their gender," the document details. The cases registered for the report reveal women journalists threatened with rape or, once detained by the security forces, forced to strip and humiliated. On another occasion, protesters beat and took the journalist's clothes.

"The data presented by UNESCO are alarming and we need an urgent collective effort to face the problem, one of the most urgent actions is the adequate training of the security forces," Canela added.

Precisely, within the recommendations offered by the report is training for members of the security forces. According to UNESCO, the organization and its associated bodies have carried out training programs on freedom of expression aimed at the security forces since 2013. At least 3,400 members of the security forces from 17 countries, including Colombia, have received this training.

The report also offers recommendations to press workers such as visibly wearing their journalist identification or receiving training on security measures, which it says should be the responsibility of media organizations. The report highlights the Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism's Security Manual for Covering Protests in the Street.

The report is also available in other languages, including Spanish, Portuguese and French.

This story was originally written in Spanish and was translated by Teresa Mioli.