The Amazon rainforest represents a danger for anyone who wishes to travel deep inside, including journalists. The recent murders of Guardian correspondent Dom Phillips and Brazilian Indigenous affairs expert Bruno Pereira made clear the risks involved in covering the Amazon.

Nevertheless, there are news outlets, initiatives and journalists who have made use of innovative methodologies, strategies and technological tools to dodge the dangers of covering this vast region spread over nine countries.

Using artificial intelligence, satellite images, geo-referencing and data journalism, journalists from Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela have developed outstanding feature stories that comprehensively address some of the environmental and social conflicts that threaten the Amazon.

The series of feature stories "Corredor Furtivo", by Joseph Poliszuk, was published between January and February of this year in Armando.info and El País. (Photo: Screenshot of "Corredor Furtivo")

In the Venezuelan state of Amazonas, considered the country's forest reserve, all mining has been prohibited since 1989. However, in recent years there has been an increase in illegal mining activity in the area, with consequences that include the arrival of organized crime groups and the transformation of the region's social fabric.

Being a vast territory - the state of Amazonas alone has a surface area similar to that of all of Uruguay - and with multiple complexities, Joseph Poliszuk, co-founder of the investigative journalism site Armando.info, knew that the phenomenon had to be covered comprehensively. However, the multiple risks posed by the Amazon made it almost impossible to start an on-the-ground investigation.

"You could make the effort to visit one location or two, but our idea was to transcend the denunciation and the chronicle and to go beyond," Poliszuk told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "We wanted to talk about a phenomenon and covering it from a single location was very difficult. That's why the idea of artificial intelligence came up. We understood that it was the only methodology that would allow us to go beyond denouncing and chronicling."

In collaboration with El País and with the support of the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network, Poliszuk and his team used artificial intelligence, satellite imagery and field reporting to locate dozens of illegal runways, mostly located near about three thousand mines and deforestation zones.

With the help of Google Earth, Poliszuk's team manually located on a map some clandestine runways. They were able to confirm their existence, which had been documented through reporting work dating back to 2016. However, it wasn't until they approached the organization Earthrise Media, based in the United States, which is dedicated to developing artificial intelligence, machine learning and design initiatives to combat climate change, that they were able to take the investigation to the next level.

Earthrise Media developed a computer vision analysis algorithm of satellite photographs that was programmed to detect images similar to the aerial captures of mines and runways that Armando.info had included in its manual map.

"Based on those samples, we programmed a robot to search for similar images. We programmed this robot based on the data and images from the Sentinel 2 satellite of the European Space Agency, which has been in the air since 2015," Poliszuk said.

In order to detect false positives in the algorithm results, the journalist did an exhaustive review with images from Google Earth and from the satellite imagery and geospatial content provider organizations Planet and DigitalGlobe, which they were able to access thanks to the support of the Pulitzer Center.

"It's not that we didn't go into the area. We went into the area, but now we had a map, and we weren't going in blindfolded. It's much easier to see the information that way," Poliszuk said. "It's not that this was a technology-only job. The technology allowed us to go into the field without being blindfolded."

The data obtained were captured in the series of feature stories "Corredor Furtivo [clandestine corridor]," published between January and February of this year in both Armando.info, from Venezuela, and El País, from Spain. These stories stand out for their data visualizations through maps and cartographies, in which the participation of the Spanish newspaper was key, according to Poliszuk.

In this six-part series, the geolocated data is contrasted with other layers of information, such as unlawful groups (Colombian guerrillas, gold mafias and Brazilian criminal groups) present in the Venezuelan Amazon, as well as the relationship of these groups with the Indigenous communities in the area.

"Corredor Furtivo" showed how technology can help circumvent dangers involved in reporting in the Amazon, although for Poliszuk, the most significant impact of the project was that the Venezuelan National Armed Forces, which had never admitted to the presence of clandestine runways despite multiple complaints from local inhabitants, finally blew up some of these structures in May of this year.

"These complaints had been sitting for years in state agencies and they did not acknowledge Indigenous people's complaints," Poliszuk said. "[With a view] from above, it was easy to confirm what they had been denouncing for years."

With a methodology similar to that of Armando.info, Brazilian independent journalist Hyury Potter, who specializes in corruption and environmental issues, also teamed up with EarthRise Media to use the same algorithm to detect illegal runways in the Brazilian Amazon.

Also as part of the Rainforest Investigations Network, Potter was also able to contrast the algorithm's results with data on deforestation, mining requirements and Brazilian legal runway records obtained via public information requests.

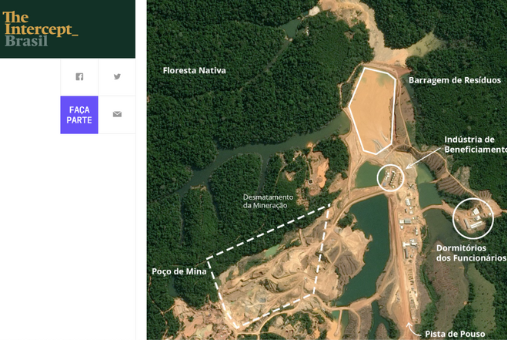

As a result, Potter published the project "Deforestation Runways: The Expansion of Illegal Mining in the Amazon," a series of feature stories published in The Intercept between September 2021 and February 2022, on the environmental impact of clandestine runways.

"Anything that looks like a runway in the middle of vegetation, between 200 and 600 meters long [around 650 and 2,000 feet], the algorithm detects it and adds it to the data," Potter told LJR. "Our job over the last seven months was to check the data [visually]. We sorted out which of those runways were legal, registered in Brazil, based on the Brazilian Aviation Agency’s data, then we loaded the data and excluded all the runways that were already registered."

At the end of the series, Potter found there were about 1,300 illegal runways in the Brazilian Amazon territory.

"There are more illegal runways in the Brazilian Amazon than runways registered by the government. This is a very shocking fact," he said.

The data obtained with artificial intelligence and traditional sources in Poliszuk and Potter's feature stories on illegal runways were localized and contrasted on maps. This geo-referencing, according to the journalists, helped significantly to place the Amazonian phenomena in its right dimension, since it is such a vast territory.

"Joining geographic science with journalism has this advantage: it allows you to look at scales of time and space over broad topics, as opposed to just narrating an event from a field perspective," Gustavo Faleiros, a journalist specializing in geo-journalism and coordinator of the Rainforest Investigations Network, told LJR. "It doesn't demerit the field perspective, but it's really a geography issue. It's a matter of perspective: you look from a ground perspective or you can look from a broader perspective."

Following the use of the algorithm in the investigations of Armando.info and The Intercept, the Pulitzer Center and Earthrise Media formed a partnership and created The Amazon Mining Watch, a web application launched in April of this year, which seeks to monitor the state of mining activity in the entire Amazon rainforest.

Hyury Potter, author of the "Deforestation Runways" series, spent nearly seven years studying geo-referenced data and maps to understand how to research the Amazon. (Photo: Screenshot from The Intercept's "Gana por Ouro" feature story)

In its beta version, the platform (available in English, Spanish and Portuguese) locates on an interactive map the mining regions detected by the algorithm. However, it is hoped that in the future it can be fed with data from other journalistic investigations and NGOs, and that information on other environmental phenomena in the region can be added.

Its goal is to enable journalists, activists and researchers to use geo-referenced information to contextualize and validate their research. The platform is open source and its methodology is available through GitHub.

"To maintain coverage [in the Amazon] for a long time we are going to need applications like this. And it doesn't just apply to mining. It could also be used to monitor climate change, because these issues are going to continue for decades," Faleiros said. "I believe that satellite or geographic information will always be very central to environmental research.”

Prior to "Deforestation runways," Potter spent nearly seven years studying geo-referenced data and maps to understand how to investigate the Amazon. His first investigative journalism project using geo-referenced data was "Amazonía Minada [Mined Amazon]", published in InfoAmazonia, which consists of a map that updates in real time the requirements for mining activities in Brazil that could affect Indigenous communities.

The platform meets the requirements of Brazil's National Mining Agency. Each time a new application is filed on Indigenous lands or protected areas, a Twitter bot publishes the name of the applicant, the threatened area, the type of mineral and the current status of the process. In addition, the map is updated every day with data added to the Agency's databases, which are geo-referenced.

"It's a very simple project, but a very big one," Potter explained. "We have done more than 10 feature stories based on this data, because we found big international mining companies and politicians connected to these requisitions, so there's a lot to say about this."

InfoAmazonia has a long expertise in producing journalistic tools and investigations based on geo-journalism, which, in the words of Gustavo Faleiros, consists of creating a dialogue between layers of data and layers of stories, where such data provide some kind of context to the stories.

Faleiros, co-founder of InfoAmazonia, shared his expertise in this area with the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network fellows, training them to conduct investigations with geo-referenced data, geospatial analysis, as well as in the use of satellite imagery and interactive maps.

"Fieldwork is obviously essential, but coupling this fieldwork with a broader view of a territory can make these investigations quite powerful," Faleiros said. "With this sort of three-pack that includes rigorous fieldwork, data work - which is largely geospatial analysis - and cross-border and transnational collaboration, this [Network] initiative has been created, which continues the work based on these three pillars."

In addition to mining, another primary activity that causes significant deforestation in the rainforest is cattle ranching.

Colombian journalist César Molinares addressed the issue of cattle ranching as a cause of deforestation through data journalism. His project "Catching the Big Fish Destroying Colombia’s Amazon" sought to investigate how the supply chains of large industries benefit from indiscriminate logging for extensive cattle ranching.

The feature stories that make up the series, published in the news outlet 360-grados.com, are based on data obtained via public information requests. These data were analyzed and presented through visualizations that contrast cattle movement with the points most affected by deforestation.

"When people talk about deforestation, they always talk in the abstract [...]. We use data to come closer to where deforestation phenomena are taking place," Molinares told LJR. “What we did with that data was to geo-reference it and cross-reference it with other deforestation and soil degradation databases, and with satellite photographs, and thus we began to locate the cattle.”

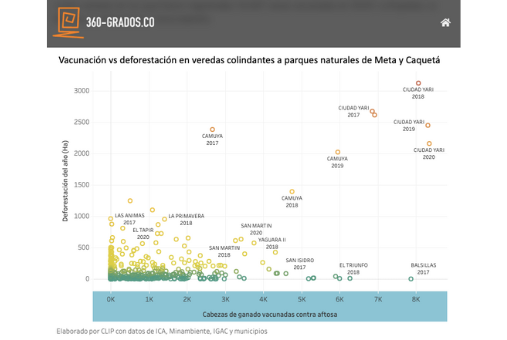

The first article in the series, "The Cattle Siege of the Amazon", reveals through an interactive map the relationship between cattle vaccination records and the regions of Colombia with the most deforestation.

Although cattle ranchers in protected areas of the Amazon do not declare the existence of their herds, in order to be able to export the products derived from them, their cows must be vaccinated. With these geo-referenced public records of vaccinated cattle, Molinares and his team were able to prove the existence of illegal herds in protected parks.

"With this project, César [Molinares] was one of the first journalists in Colombia to get his hands on animal health data. He was able to prove that even though they were illegal, cattle herds were receiving vaccinations in national parks," Faleiros said.

The data visualizations were carried out by the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) with technical support from the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development, who have proven experience in geo-referencing and identification of deforestation hotspots. The project was also supported by the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network.

Thanks to data analysis and map visualization, César Molinares was able to do more targeted and focused field reporting on specific points in the jungle (Photo: Screenshot of the report "The Cattle Siege of the Amazon" from 360-grados.co)

By analyzing the data and visualizing it on maps, Molinares was able to do more targeted and focused field reporting at specific points in the jungle, where they talked to the inhabitants to find out if they were aware of what was happening. In this way, they found that there was a relationship between the data on illegal cattle ranching and episodes of violence in some territories.

"I believe that in Colombia there had never been an investigation that tied the data to social phenomena or violence in the territories," Molinares said. "When you geo-reference, you begin to identify socio-environmental and social conflicts, or conflicts in general over land issues.”

Molinares added that contrasting data allowed him to identify actors and cases derived from illegal cattle ranching activities in the Amazon, such as murders of environmental leaders and park rangers who had begun to document cases of deforestation. These cases are generating new feature stories that are currently in process.

Data journalism helps to carry out investigations in a more intuitive and focused way, according to Molinares. For this reason, he has focused on developing a strategy of access to information to take advantage of legal loopholes and avoid obstacles placed by government agencies to avoid providing information.

"The argument we have established, and we have already won several court battles, is that because [the Amazon] is a matter of public interest in which there should be transparency and access to information, the data should not be restricted," he said. "So we have fought several court battles in which we managed to establish a precedent for state entities to hand over the information."