By Aileen Ford

When Miguel Ángel López Solana received the news on August 1 that fellow journalist Rubén Espinosa had been murdered in Mexico City, the entire nightmare that had forced him to escape from Veracruz four years earlier came back to him.

On June 20, 2011, López Solana learned that his mother, father and younger brother had been found executed in the family’s residence in the port of Veracruz (México). According to initial reports, unidentified armed suspects had arrived at the home around six in the morning and opened fire. The exact motive for the crime was unknown, however.

Miguel Ángel’s father and brother were also journalists. His father, Miguel Ángel López Velasco, better known by his pen name ‘Milo Vera’, had worked for years as a columnist for the daily publication Notiver covering stories about security and drug trafficking. His brother, the youngest son in the family, had specialized in photographing politics and the police beat. According to Reporters Without Borders, López Velasco had received threats related to his profession from organized crime groups.

In 2007, for example, drug traffickers had left a human head at the door of Notiver with the following message: “Here we are leaving you a gift […] a lot of heads will roll like this, ‘Milovel’ and many others know it, there will be a hundred heads for my father. Sincerely, the son of Mario Sánchez and La Gente Nueva.” La Gente Nueva refers to a group of armed hitmen whose job is to protect the Sinaloa Cartel.

In the few months following the murder of his family, López Solana would see several of his colleagues die, including photojournalists Gabriel Huge and Guillermo Luna Varela, also contributors to Notiver; Esteban Rodríguez, who had previously worked for the Veracruz daily AZ; Ana Irasema Becerra Jiménez, an administrative employee for the daily El Dictamen; and Regina Martínez, correspondent in the state for the weekly Proceso. López Solana could not wait to see if he would be the next victim of this violence. Following his intuition, he made the decision to go into self-exile in Mexico City, or the Federal District (D.F.).

Nevertheless, over time, López no longer felt safe in the D.F., and along with his wife, the two decided to flee to the United States to seek political asylum. In 2013, they were successful in their petition, and López Solana remains convinced to this day that if he had not left Veracruz, he would be dead.

Thus, when López Solana was informed about the July 31 murder of photojournalist Rubén Espinosa in Mexico City, he felt a profound pain. Four years after López Solana fled to the D.F. from Veracruz in search of protection, Espinosa did the same. But Espinosa was unable to find it. At an apartment in the Narvarte neighborhood, death arrived for him and four women - Olivia Alejandra Negrete, Nadia Vera, Mile Virginia Martín y Yesenia Quiroz.

López Solana agreed to share with the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas his reflections about Espinosa’s murder, the dangers that journalists currently face in his home state of Veracruz and all of Mexico, as well as the significance in his life of having received asylum.

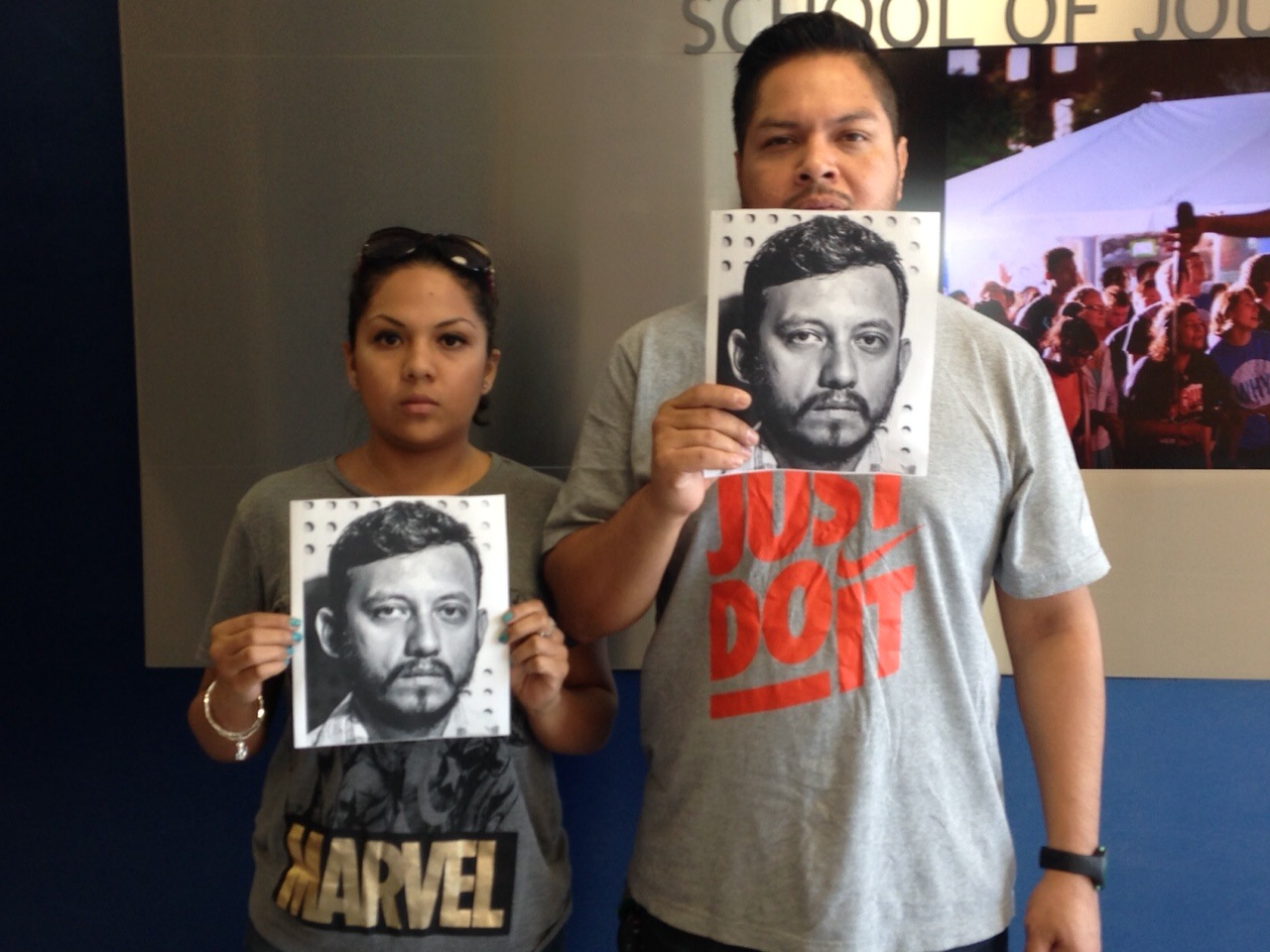

Journalist Miguel Ángel López Solana and his wife Vanessa pose with a photo of Rubén Espinosa on August 5th, 2015. (Aileen Ford/Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas)

Journalist Miguel Ángel López Solana and his wife Vanessa pose with a photo of Rubén Espinosa on August 5th, 2015. (Aileen Ford/Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas)Knight Center: What was the first thing that went through your mind when you learned about the murder of photojournalist Rubén Espinosa and four other women in Mexico City?

Miguel Ángel López Solana: It hurts us…it hurt us. It hurt us because of everything that we have suffered, the murder of a fellow [journalist], all my fellow journalists, and, more than anything, Veracruz. Whether or not it is complicit, the government of Javier Duarte [current governor of Veracruz] is an accomplice by omission. It considers it unnecessary to carry out investigations thoroughly.

[The governor] has made declarations to communication workers telling them to be careful. More than declarations, these seem to be threats. And what Javier Duarte does not realize, being a politician, is that today he is known worldwide because many journalists have been murdered in his state […] and this had led Veracruz to become known because there is blood and gunfire in the state.

Rubén always supported the movement to shed light on the murder of Regina Martínez. Rubén was at the front of those marches. Up to a certain point, he was a social justice fighter, as one of the reporters, defending reporters.

KC: And also the students were beaten in Xalapa and different social movements…

MALS: Journalists are part of the people’s voice, the citizen’s voice. There are many families in Mexico who have lost children, lost their husband, lost their mother. We are a little tired of dealing with death every day in Mexico, seeing it head on, knowing that if you go out on the street, you run a high risk of losing your life without having done anything illegal really. There might be a gunfight with crossfire. It has already been seen how children and mothers have died in these types of regrettable actions.

KC: And what is happening in Veracruz, particularly in recent years, to unleash a concentrated wave of extreme violence against journalists, compared to 2009 or 2010 when the violence was more concentrated in the north of the country, like in Coahuila or Chihuahua, for example?

MALS: I think that what happened specifically [in Veracruz], and in general in Mexico, was the ‘cucaracha’ effect. Perhaps the government is able to combat some criminal groups along the Mexican border with the United States, but this ends up benefitting other groups. So, what these other criminal groups did was to go further south.

And, just like those Colombian bosses who said: “money or bullets," or you want my money or you want my bullets, they are acting with bullets, because they have not been able to force the journalist to fold his hands. He continues forward, informing. My colleagues in Veracruz continue informing under a very high risk […] The minimum guarantees to exercise freedom of expression in Veracruz do not exist.

In Veracruz, even we journalists and photographers do not know what is happening. Just like everyone else, we cannot find a reason why they would be attacking us, murdering us, following us, persecuting us.

KC: Espinosa is the first press worker to die in the D.F. due to events that happened in Veracruz or another state in the country. What is the importance of the fact that he was murdered there?

MALS: Yes, people often say that the D.F. was the only place where you would think you could be safe, beyond common crime that exists there like car thefts and pickpocketing.

I lived in the Federal District. I lived in the Colonia Del Valle, too. I lived nearby where Espinosa was murdered, which is considered a calm and safe place. I walked on those streets, but the moment also arrived when I felt unsafe, I felt like I was being followed, and overnight I disappeared from the Federal District.

I believe a colleague from Xalapa has declared how she saw the way Rubén Espinosa was pursued; he was harassed. It is living with fear. I do not know…you cannot live. In Veracruz, you live with fear. Fear adopts you, you know that it is there to the side, that you go out on the street and look one way and then the other.

Since the murder of my family, a wave of violence has come and increased instead of decreased. It is like a snowball that grows more, and more, and more.

KC: What types of support of resources do journalists have when they are in danger? There is information that the photojournalist Espinosa did not ask for the help of the mechanism for the protection of journalists.

MALS: I asked for it in the D.F. They put me in a hotel two days and that was it. It did not do anything. They told me: “Well, you have to sign here, and it is up to you to make sure you survive going forward."

Maybe he saw too many cases where this type of mechanism does not work. A commission for the freedom of expression exists in the state of Veracruz, but it is only known for the large waste of money among the people who make up the group. They only dedicate themselves to spending money, seeing pretty things, and saying that the governor is fine. They only applaud the governor.

That is not journalism; a journalist is not here for that. A journalist is here to make known what is wrong in society and what is affecting society. I think that the defense mechanisms to protect journalists still need to be improved, and without a doubt, they failed. They failed because they should have been monitoring Rubén more, they should have been paying a little more attention. Not only the governmental mechanisms, but also the international protection mechanisms for journalists.

KC: So, how is the status of freedom of expression in Veracruz?

MALS: It does not exist. Freedom of expression in the state of Veracruz and Mexico does not exist. It does not exist because you run the risk of losing your life, that your family members lose their life, really that one day you will disappear and they will not find you, or in the worst case, that they kill you and say that a car ran you over, or you committed suicide, or that what happened to you was just an isolated case. And that investigation goes cold, or gets thrown into the garbage, and the murder remains in impunity.

That is how it was [in Veracruz], you had to silence yourself, not say anything, and after being kidnapped that was it. Can you imagine having a pistol in your mouth? They put a pistol in my mouth. They kidnapped me, handcuffed me, and beat me. After that, I did not want to leave my house. My house. […] And afterward, you look one way and then the other. You felt like they were going to kill you, and I said: “But why? Well, I don’t know…I don’t know. I have no idea! They’re crazy. And it’s like a person who is on drugs and has guns, and he just goes out and kills. That’s it. It’s done.”

KC: Do you have any hope that a resolution will be found in these murder cases or will the impunity be too powerful?

MALS: Unfortunately, we know that the things happening in Mexico are only due to corruption and impunity. I think that in Veracruz they should hold a forum with international organizations where they agree to create some type of organization in Veracruz whose representatives are from the media. Journalists, truly journalists. Not those directors and owners who receive government money through calls, publicity or agreements. Truly journalists.

Maybe the will exists among citizens and journalists to see justice done and have all that move forward […] That type of petition does not have to come from the government. It has to be society itself, I think with the help of international organizations and organizations that defend freedom of expression and human rights.

KC: And what do you think of the pressure that is taking place these days with the public mobilization and protests in Mexico?

MALS: Without a doubt, right now there is big pressure being applied and it’s becoming more known that in unity there is strength. That really, something very, very serious is happening in Veracruz. That behind all those murders exists a Machiavellian mind. They are planned and pre-meditated murders conceived in the most clandestine manner possible.

KC: Changing topics a little, I would like to know about your experience seeing this situation from afar in the United States. How has your life changed since coming here to seek asylum?

MALS: Coming here, I was reborn. When they gave me political asylum, I was reborn at 30 years old. I really didn’t know what awaited me in this country, and when I saw it, it was the best for me. It’s a country full of opportunities.

What I can say is that, honestly, I’m much, much better than if I were in Veracruz. I’m not so mistrustful anymore; I’m only mistrustful now [laughter]. But, yes, we think it’s been going ok for us, and that we’ve regained tranquility.

KC: In 2012, only 1.4 percent of Mexican applicants received political asylum in the United States, compared to 42 percent of Chinese applicants. Keeping in mind such a low rate and the fact that you form part of a small group of Mexican journalists who currently live in the country with political asylum, do you have any reflections about the process of fighting and winning an asylum case in this country? Does it seem to you like there is a barrier existing in the United States for those who come here fleeing insecurity in Mexico?

MALS: It’s really difficult from the beginning. First, to make the decision that you’re going into exile, and then to know that you’re not going to be in your home, that you’re not going to be in the place where you were born. The first exile, I’ll repeat, was to the D.F., and the second one went further until we arrived in the United States. It’s kind of terrible because you know you’re in another country and there’s no going back.

But I think that beyond asylum, what you most want is that the laws are carried out in your country. What really happened with us is that justice was done. The laws of this country judged us and determined that we were able to receive asylum.

They used to ask me, “What did you feel when they told you that you had asylum?” and when they notified me, I didn’t know whether to cry, or sing, or be happy or sad. Even now I still don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do because it’s very painful to know that what you’re going through can be published and proven, and because of that you’re able to obtain asylum. It fills you with joy, but then you remember that it’s because of the murder of your family that you’re here.

If I hadn’t left Veracruz to go into exile in Mexico, I would be dead. Almost all my colleagues are dead. The ones I worked with every day, the ones I greeted every day, the ones I spent time with, they’re dead.

But it’s a dilemma. More than a dilemma, you can’t compare having asylum with all you had to go through to have it. You wish you could return to your country and not have asylum. You wish that nothing had ever happened. You wish you had your family instead of asylum.

KC: Is there anything else about your experience or what is happening now in Mexico that you think is important for the public to know?

MALS: Without a doubt, the colleagues in Veracruz are living through horror. Horror because it’s very difficult to go out and realize that you can lose your life. In Veracruz, it seems like they’re living in anarchy. The governor doesn’t really care what citizens think or do anything to solve the forced disappearances and kidnappings. We’re tired of seeing our colleagues die, of seeing how friends and family lose one of their members, how everything has fallen apart because of the violence.

It’s very difficult to know that all the murders still remain in impunity, and again and again, I’ll demand that they solve the murder of my family so that it doesn’t get thrown in the trash or frozen.

meote from the editor: This story was originally published by the Knight Center’s blog Journalism in the Americas, the predecessor of LatAm Journalism Review.