With the murder of Gerardo Bedoya Borrero, director of the opinion section of the Cali newspaper El País in Colombia, the last strong voice of protest in Cali was gone, according to the journalist who investigated his murder, Ana Arana. On the night of March 20, 1997, Bedoya Borrero was leaving an apartment complex when he was shot at least five times in his abdomen. Authorities did not define whether there was one or two murderers.

The journalist, also a columnist for the newspaper, was recognized for his criticism of the corrupt political class, drug trafficking and his links with different actors in the State. Twenty-seven years later, the truth about his crime is not known: neither the material perpetrators nor the intellectual perpetrators have been found. Until April 2020, the investigation into his crime remained in the evidence collection stage.

The impunity in the case of Bedoya Borrero led to him being chosen as the first case for the recent campaign of the Inter American Press Association (IAPA) “Voces que reclaman justicia” (Voices claiming justice).

Launched on March 18, the main objective of the campaign is to “rescue the memory of dozens of journalists murdered in Latin America in recent decades,” Carlos Lauría, executive director of the IAPA, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

According to Lauría, this campaign is also embodied in the work that the IAPA has done for years to combat impunity in crimes against journalists in the region. Part of this work includes, for example, presenting cases before the Inter-American Human Rights System.

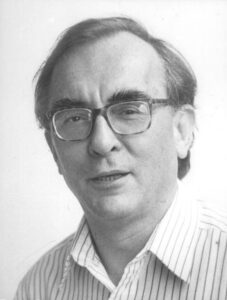

Colombian journalist Gerardo Bedoya Borrero murdered in Cali in 1997. His crime remains unpunished. (Photo: Archive El País, Cali)

That’s what it just did with the crime of Bedoya Borrero. On Sept. 23, 1999, the IAPA presented the case before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) alleging the responsibility of the Colombian State in the murder of the journalist and the lack of investigation and punishment of those responsible.

After years of dialogue between the IAPA as representative of the victims, the Colombian State and the IACHR, the parties reached a friendly agreement on Aug. 16, 2019. As part of the Friendly Settlement Agreement, the State recognized its international responsibility for not investigating the crime, among other violations to human rights.

On Sept. 30, 2019, in a public event, in addition to recognizing this responsibility, the Colombian State apologized to his family members.

“We apologize for the violation of human rights of which Gerardo Bedoya Borrero and his family were victims. This episode should never have happened. And it should not be repeated, in a social State of law in which the protection of life, personal integrity, access to justice and freedom of expression are essential pillars of a democratic society," said then-Presidential Advisor for Human Rights and International Affairs, Francisco Barbosa Delgado.

Two years earlier, in March 2017, the murder of Bedoya Borrero was declared a crime against humanity, preventing its statute of limitations.

However, despite the friendly solution and the imprescriptibility of the crime, the truth is that it remains unpunished.

“Precisely, the initiative fundamentally has to do with persevering in this demand for justice in the face of a level of impunity in most of the countries where journalists are murdered,” said Lauría, who pointed out that the failure to seek justice is a common problem in countries of the region.

“The aggravating factor of impunity in the issue of violence against journalists is that those who perpetrate these types of acts, seeing that there is no punishment for those responsible, feel that they have a green light and that they can continue committing these types of crimes openly without being punished, without receiving justice. Therefore, this is a permanent grievance,” he added.

For Vicky Perea, director of El País, the selection of Bedoya Borrero's case is “an honor” not only for the media outlet where he worked, but for Cali society.

“His is the clearest example of impunity by the Colombian justice system for crimes committed against press freedom,” Perea told LJR. “Gerardo, from his column, maintained a clear and direct position against corruption in politics, drug trafficking, its links with different actors in the State, including its Armed Forces, and against all those phenomena that at the time threatened and affected in a very serious way the lives of Colombians, the Valle del Cauca and Cali.”

She also highlighted the lack of diligence despite the fact that the crime was declared as being against humanity.

"By presenting his case to the public again, through 'Voices claiming justice,' it is to be hoped that his judicial process will be reactivated and now it will be possible to know who were the masterminds of his crime, who were the material authors and that finally, justice is done for him, for his family, for the newspaper El País de Cali, for Colombian journalism and for the exercise of the free press in the world,” Perea said.

Each month, the IAPA campaign will highlight a case in which justice has not been achieved, and in this way pay tribute to their work, their legacy without forgetting the demand for justice, Lauría explained.

IAPA members are invited to join the campaign in different ways: either by republishing the statement that highlights each journalist, by doing their own reports on the case, with an editorial, etc. This same invitation is extended to civil society in general, organizations defending press freedom and media that are not members of the IAPA.

“[Echoing] a message from the president of the impunity subcommittee (of the IAPA, Andrea Miranda), we invite all those who understand and appreciate journalistic work and who are aware of the importance of the administration of justice in crimes against journalists and who want to contribute to keeping the memory of our fallen colleagues alive,” Lauría said.

Perea, from El País, points out the importance of the project to continue the fight against impunity, which she considers the “worst enemy” of press freedom.

“There are multiple events that have not gone unpunished or in which the judicial apparatus of the countries have been forced not to close the investigations, because the IAPA has exerted the necessary pressure on the States or their judicial branches,” Perea said. “The voices, the words of those who have been murdered for practicing the profession of journalism and fulfilling the work they do of being spokespersons for society, have to continue in the collective memory until justice is done for them.”