The year 2023 saw a decrease in murders of journalists around the world: a trend also seen in Latin America and the Caribbean. Despite the significance of that statistic, expert voices point out that it does not represent an improvement in the conditions for practicing journalism and that it could lead to the phenomenon of zones of silence.

Civil society organizations that participate in the National Observatory of Violence against Journalists and Social Communicators welcome the “good will” of the Brazilian government, but state that a lack of personnel and prioritization of the issue are obstacles to its effectiveness. Changes in the Ministry of Justice, where the Observatory is housed, also concern them.

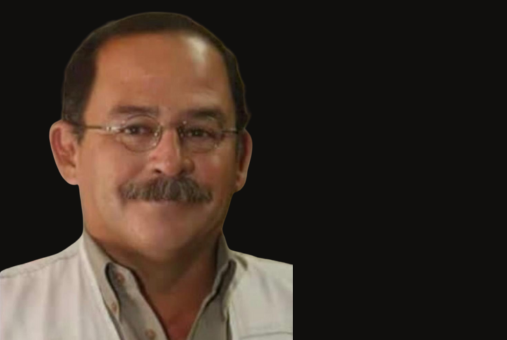

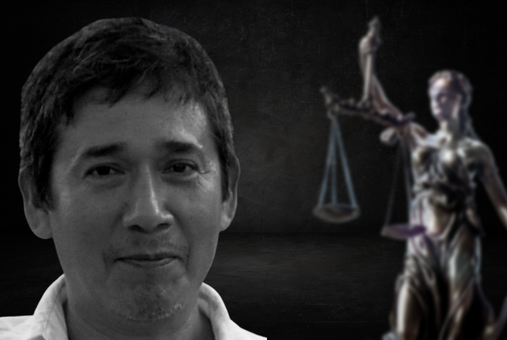

It has been 11 years since Ecuadorian journalist Fausto Valdiviezo was killed. His brother and experts believe that the case has not been solved because of a lack of investigation on the part of authorities because he was a journalist.

On the occasion of Journalist's Day in Guatemala on Nov. 30, a collective of journalists under NoNosCallarán [We won’t be silenced] spoke out against the attacks they have been exposed to for practicing their profession and held a sit-in against the criminalization of journalists in front of the public prosecutor's office.

Stigmatization, threats, detentions, and intimidation are some of the attacks faced by journalists when covering elections in Latin America. In the last semester of 2023, these attacks became evident in the electoral processes in Argentina, Colombia and Venezuela.

A Superior Court of Colombia recently sentenced one of those involved in the case of aggravated torture against journalist Claudia Julieta Duque to 12 years in prison. The journalist said the sentence left a “bitter” taste because the convicted former intelligence official is on the run.

On Nov. 2, 2023, the world marks another International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists. Impunity in cases of violence against members of the media continues to be the norm as killers largely go free. In the Americas, Haiti, Brazil and Mexico top the list of countries globally where murders of journalists go unpunished.

To mark the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, which is celebrated every Nov. 2, LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) is highlighting four cases of journalists from Latin America and the Caribbean that, for the most part, remain unpunished.

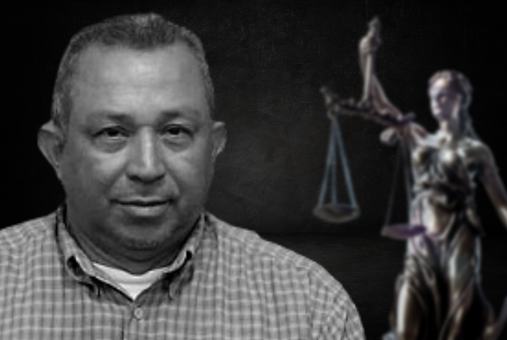

The investigation into the murder of journalist Gabriel Hernández in Honduras has not made any progress in the nearly five years since he was killed. Lack of access to information as well as a failure to protect him before he was killed are questions before authorities.

Brazilian journalist Pedro Palma was murdered on Feb. 13, 2014 in Miguel Pereira in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Nine years later, the investigation into the crime remains open and no one has been held responsible. This is one of 25 cases in Brazil with “complete impunity,” according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. It illustrates obstacles to holding accountable the perpetrators and masterminds of crimes against journalists in the country.

Over the past twenty years, Colombian journalist Claudia Duque has been targeted for her work. She’s been abducted, tortured, threatened, followed and surveilled. Justice for these crimes has been limited. Despite this, she continues to focus on her own journalistic investigations, mainly into crimes against other journalists.

On Jan. 2, 2015, Mexican journalist Moisés Sánchez Cerezo was abducted from his home by armed men. Days later his body was found lifeless and with signs of torture. In the past almost nine years, his family has been dedicated to finding justice with different governments, without much success.