More than three years ago, a group of Paraguayan women journalists started a WhatsApp group to share their experiences of sexual harassment and workplace mistreatment at one of the country’s largest media conglomerates. Some also reported their cases to the Ministry of Labor or filed charges in court. Now, after years of persecution and legal proceedings, some are calling recent court rulings “historic” and a vindication of their fight.

The first victory for the journalists came in November 2025 when Carlos Granada, former top newsroom manager at the Albavisión Group, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for coercion, sexual coercion and sexual harassment against six women journalists.

The next month, Lorena Romero, a former producer for the company, won a workplace mistreatment case against Albavisión. Romero, who was also one of the six journalists who won the criminal case against Granada, said she left the newsroom after being subjected to workplace mistreatment following her reporting of Granada and for supporting public demonstrations demanding justice in these cases.

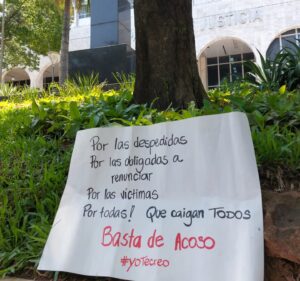

In 2022, journalists from Albavisión Paraguay demonstrated against sexual harassment and workplace mistreatment. (Photo: Courtesy)

And in February 2026, a judge ordered Albavisión to reinstate journalist Angie Prieto, ruling that her dismissal was unjustified. Prieto said that the dismissal also occurred because she denounced and publicly protested Granada's harassment of her and other colleagues.

The legal decisions are striking in Paraguay, a country where eight out of ten women journalists say they have suffered sexual harassment.

“This is an historic ruling and a vindication for women, for women journalists, for journalists and communicators, and for the working class in general, that we must not remain silent in the face of violations of our rights and abuses of power,” Prieto told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) after the most recent decision. “It is a clear and powerful message in favor of freedom of expression and association.”

The struggle Prieto refers to began around May 2022 when at least four of her colleagues resigned from the media outlet where she worked.

At that time, Prieto was working as a journalist and presenter for Channel 9, part of the Albavisión Group, a media conglomerate with a presence in 15 countries in Latin America. In Paraguay, specifically, it is one of the three most important media conglomerates, controlling the National Television System (SNT - Channel 9), Paravisión, C9N, the regional channel Sur TV, and RQP.

Her investigation into the departures of her colleagues led to the discovery that they claimed to be victims of sexual harassment. Prieto, who remained at the channel, said she and other women journalists felt the need to support and accompany them through this process.

“We felt in that position of wanting to help them, of wanting to try to put a name to what was happening,” Prieto said.

Because of her position and recognition at the media outlet, she said she felt obligated to speak out about what the women were saying.

“That’s when we realized that it was practically a situation that occurred in many media outlets, and that no woman, no journalist, wanted or could say, ‘Yes, it’s true, this is happening to me,’ because we were afraid, afraid of losing our jobs, afraid of not being believed. So that’s when we found strength, enough strength among ourselves,” she said.

They created the WhatsApp group called “Yo te creo” (I believe you), a kind of “support group”, Prieto said, where many more women journalists began to share what they were experiencing or had experienced.

Perhaps the most “impactful” moment, Prieto said, was realizing and understanding that they were victims of what they usually reported on: gender violence.

“Identifying with those situations and consciously telling ourselves that yes, I was a victim of this, I was also part of this, but as victims, it also affected us psychologically a lot,” Prieto said.

The movement was already unstoppable. By July 2022, the Network of Women Journalists and Communicators of Paraguay demanded that the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security intervene in the media outlet and sanction it for “covering up harassers” and punishing women who report abuse.

And while at first, Prieto said, they felt the support of Albavisión, with the collection of complaints and information, they later found themselves victims of persecution and workplace harassment.

Angie Prieto durante su época de periodsita y presentadora para el grupo Albavisión. (Foto: Cortesía)

Prieto, for example, was sued by the group's manager, Marcelo Fleitas, for defamation based on the WhatsApp group and other statements she had made. She was acquitted in 2024.

In the legal case concerning Prieto’s dismissal, Albavisión’s defense said it was justified because she had defamed senior management. Taking into account the defamation acquittal, the court ruled in the recent 2026 case that her firing was not justified and ordered her reinstatement as well as financial compensation.

“With this ruling, I only hope to clear my name and my image, which were severely damaged by an unjustified and illegal dismissal,” Prieto said. “I hope to be able to get my professional life back on track, which was put on hold for almost four years, and return stronger than ever to continue doing what I love, which is journalism.”

However, she said she would not return to a place that “hurt her so much."

LJR requested statements from the Albavisión Group through its manager, but had not received a response as of publication.

Prieto said she suffered not only workplace harassment but also sexual harassment. She was one of at least 20 women journalists who accused Carlos Granada. The trial against Granada, however, concerned the case of six other journalists. Prieto's testimony was heard at the trial, but it was not admitted into the legal case due to the statute of limitations prescribing.

However, she accepted the sentence against Granada as a form of redress.

“We felt very heard,” Prieto said about the sexual harassment trial. “It’s a landmark case for us as journalists, but more than that, as women, as a society, to carry forward this entire process with all it cost us, with all the losses we suffered. It was very, very impactful. Like a before and after. Even in our lives, I could say.”

Prieto, who has become the face of the women who filed the complaint, described how the events impacted the journalists' lives. She said at least four had to leave the country, others left journalism permanently after failing to find other employment. During the trial, it was reported that some even considered suicide, according to news outlet ABC.

Granada was sentenced to 10 years in prison in the first instance. On Dec. 19, the sentence was upheld by a judge, but there are still avenues for appeal, Mirta Moragas, a lawyer with the Feminist Legal Clinic, the organization that supported the group of women journalists, explained to LJR.

Granada has maintained his innocence and has never accepted the charges. His defense team announced they will appeal the decision.

One of the messages left outside the Palace of Justice in Asunción (Paraguay) when Carlos Granada, a former top newsroom manager of the Albavisión group, was first charged in 2022 for the crimes of sexual coercion and harassment, among others. (Photo: Courtesy)

Despite the delay in this trial reaching a conclusion, Moragas highlights the impact of the sentence against Granada.

“It’s a case of great magnitude,” Moragas said. “Certainly, there were six victims in total at the oral trial, but the system that allowed this person to operate in this way for several years, whether through action or omission, is of a very large scale.”

But perhaps the most significant aspect of the ruling is that it helps to illustrate the consequences of sexual harassment for women in the workplace, the lawyer said. The ruling's characterization of harassment demonstrates the impact on women who are victims, and even on women who are not, Moragas said.

“That’s why it’s said that harassment is a continuum,” Moragas said. “There’s sexual harassment, abuse of authority and if the person doesn’t give in to those demands, what follows is a context of retaliation.”

The reprisals in this case included changes to the journalists' schedules, less airtime and the obligation to wear certain types of clothing that sought to exploit women's sexuality, Moragas said.

The lawyer also highlighted how this case demonstrated the difficulty women journalists face in reporting such incidents, not only due to retaliation in the workplace but also within the broader media landscape. The women journalists who were fired or resigned struggled to find new positions in journalism, she said.

“The fact that no other media outlet has taken in the journalists who left this channel, many of them very talented, that's also a message. It's a message of punishment for those who speak out,” Moragas said. “And that's also a very powerful and terrible message for women in general. I mean, what will happen to you if you speak out? And I think there's still a debt owed by the media, by the State, by society in general, and well, let's hope that changes in the short to medium term.”

A 2022 survey in Paraguay revealed that 60% of women working in the press have been victims of sexual harassment. 22.9% indicated they may have experienced sexual harassment, while 17.1% answered no. 56.9% reported experiencing mobbing (workplace harassment).

The case of Paraguay is part of the regrettable panorama of Latin America and even the world where women journalists face both sexual violence in their workplaces and online violence.

The 2024 #MediosSinViolencia study, conducted by the Argentine organization Comunicación para la Igualdad with support from UNESCO, found that 75% of those interviewed in Latin America said they knew of at least one case of gender-based violence against women journalists, both happening online and in the real world. Almost half (48%) said these cases of violence occurred in the journalists' primary workplace, that is, a newsroom, television studio or radio station.

The study also reported that the main perpetrators in offline environments were allegedly people in management positions (49%) at the media outlets where the victims worked, and colleagues at the same hierarchical level (27%). Psychological and verbal violence (65.6%) and sexual harassment (28%) are the main types of gender-based violence against women journalists.

Interviews were conducted with 108 journalists and managers, men and women, from 95 media outlets in 14 Latin American countries.

This article was translated with AI assistance and reviewed by Teresa Mioli