Journalist Paula Bianchi graduated from a renowned public federal university in Brazil. However, according to her, her teachers “were horrified” by journalists who worked in the newsrooms of large media outlets. “They spoke in a way as if the newsrooms were a den of co-opted people,” she laughed when telling LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Bianchi's experience is common to many people who went to traditional journalism schools in Brazil. Many of these programs have professors far from the journalism market and who tend to focus more on theory than practice. Thus, it is common for the transformations that shake up newsrooms at increasingly shorter intervals to be little debated during journalists' academic training.

To bridge the gap between universities and newsrooms, some Brazilian media outlets offer training programs that combine classes on topics related to the daily life of the profession and the experience of working in a professional newsroom. In Brazil, the two longest-running initiatives are promoted by two of the country's main newspapers: Folha de S.Paulo and Estadão, both located in São Paulo. With more than 30 years of existence, these two initiatives have been updated to take into account changes in the field and the demand for greater diversity – racial, gender, regional – in Brazilian journalism.

In 2024, Folha will hold the 68th Daily Journalism Training Program, and for the first time it has reserved 50% of vacancies for Black or Indigenous people, or people with disabilities. Meanwhile, Folha, is taking a stance against racial quotas in its newsrooms. The Folha program, which has been running since 1988, is open to people with degrees in any field and has already trained around 700 people. A third of the professionals who currently work in the newsroom of the paper went through the program, Suzana Singer, Folha's training editor, told LJR.

Estadão is holding its 34th Estadão Journalism Course this year, which has been held annually since 1990 (with the exception of 2020, due to the start of the coronavirus pandemic). Aimed at people in the last semester of college or recently graduated in journalism, the course has so far trained around 1,030 young journalists, Carla Miranda, training coordinator at Estadão, told LJR.

Born in the south of Brazil, Bianchi graduated in journalism in 2009. She saw the Estadão course as an opportunity to work at a large newspaper and enter the job market in São Paulo, the largest city in the country. Now editor of Repórter Brasil, she was part of the 2010 class of the Curso de Focas, as the Estadão program is known – the term “foca” (seal) is used in Brazil to describe journalists at the beginning of their careers.

Paula Bianchi (first on the left) with colleagues during Estadão's training program in 2010. (Courtesy)

“College was super cool, but we talked very little about the journalistic process. We talked about philosophy, literature, anthropology, economics, and we had some more journalism classes (...) I was very impressed when I arrived at Estadão and Chico [Francisco Ornellas, then course coordinator] said ‘the profession.’ I thought 'damn, there's a way to do this here with guidelines, there's a way to think about how to do the best interview possible, how to write the best text possible.’ That was really cool, because I felt a seriousness about my profession that until then, in college, I hadn’t felt,” she said.

Miranda considers that the distance between the teaching of journalism at universities and the professional practice of journalism is more pronounced in Brazil than in other countries. This is what would have led to the creation of training programs like those at Estadão and Folha, she said.

“In other countries there is a much greater connection between research carried out at universities and the journalism market. Therefore, you would not need to take courses or activities that help complement this training. (...) Colleges, unfortunately, end up becoming less connected with the needs that are happening on the other side. And for the journalism market, this is also bad, because the market is on a day-to-day basis, on deadline, and loses part of [the academy's] reflections,” Miranda said.

Another motivation for creating the Estadão course in 1990 was the need to “add new talent” to the journalism market, Chico Ornellas, who coordinated the training course from its beginning until 2012, told LJR.

According to him, then-director of the newspaper, Júlio César Ferreira de Mesquita Neto, brought a question to a meeting of the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) concerning how to solve the deficit of young professionals available to work in his newsroom. There, according to Ornellas, Mesquita Neto heard from Jayme Sirotsky, then president of the RBS media group, from Rio Grande do Sul, about the Applied Journalism Course that RBS had launched in 1989. This course ended in the mid-1990s.

Mesquita Neto then brought the idea to Estadão and called on Ornellas to coordinate this initiative, he said. At that time, Ornellas had already worked for 22 years in the publication’s newsroom and held various positions, such as reporter, editor and chief reporter.

Based on demand from the young journalists who were part of the first editions, the Estadão course gained academic recognition as a university extension, due to a partnership with the University of Navarra, in Spain. And having participated in IAPA assemblies talking about the course, Ornellas said that he began to receive requests from young journalists from other countries who also wanted to participate in the program. That's why they opened up to two extra places in each edition for foreigners, in addition to the 30 places for Brazilians.

Carla Miranda, training coordinator at Estadão, participated in its training program in 1997. (Courtesy)

In addition to serving as a breeding ground for future Estadão employees, the course also made the graduates' data available to other media outlets that might be interested in hiring them. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the Banco Estado de Talentos, which contained the profiles and contact information of journalists who completed the course, was a printed document sent to newsrooms in several states across the country, Ornellas said. It then became an online platform, which is no longer up.

The experience with the general course led the newspaper to create the Estadão Economic Journalism Course in 2011. Around 350 people have already undergone the training, which also takes place annually and has an academic partnership with the Fundação Getúlio Vargas School of Economics (EESP/FGV ). According to Miranda, this course was created to serve not only Estadão's economic coverage, but also the Estado group's real-time economic news agency, Broadcast. Students take macroeconomics, finance and politics classes in addition to journalism subjects.

Folha, in turn, debuted its training program in March 1988. Since then, it has carried out two or three editions a year, in addition to programs aimed at specific areas such as cultural journalism, science and health coverage and photography.

“We once did a very interesting class with only professionals over 40 years old. They nicknamed themselves ‘phocosaurs’, because they would be seals and dinosaurs,” laughed Suzana Singer, training editor at Folha, in conversation with LJR.

Unlike the Estadão course, the Folha training program is open to professionals from any field.

“The idea is to introduce people to the principles of Folha’s journalism,” Singer explained. “It’s a chance for a person who studied law, for example, to have time to familiarize themselves. She will not learn what someone else learned in college [of journalism], but she will become familiar with the terms, with the logic [of journalism], with the work.”

Even so, the percentage of journalists is around 60 to 70% of the total selected for each edition, Singer said. And demand for the course remains high: the 2020 edition, the first held 100% online due to the coronavirus pandemic, had 3,388 applications for 20 places, or around 170 candidates per place. According to Folha's training editor, editions in recent years maintained this rate of candidates per vacancy.

Brazil's current vice-president, Geraldo Alckmin, then vice-governor of São Paulo, was interviewed by Folha trainees in 1998. (Photo: Cleo Velleda/ Folha Imagem)

The next edition of Folha's training, which begins in April, will have an emphasis on economics, with classes covering topics such as macroeconomics, coverage of companies, international economics and Brazilian economic history, Singer said. In addition, trainees will also take journalism classes dealing with ethical issues, relationships with sources, pillars of Folha's editorial project, how to prepare for an interview and the importance of the other side, the editor said. And they’ll also be trained in text, with style workshops and grammar classes.

For many years, the program was dedicated to teaching trainees how to create a printed newspaper, emphasizing layout and closing the paper, Singer said. Today these topics are still addressed, but “minimally,” she said.

“We have a big job to explain this new ecosystem of the internet and social networks. They have classes with the audience and engagement staff. The basics remain the same: Folha's pillars have not changed in that time. (...) But everything else has changed. We teach how to do internet research and data journalism. We are passing on all these things to them, because it is very different from when I started, for example,” said Singer, who joined Folha in 1987, a year before the program started.

Journalist Anelise Gonçalves went through Folha’s training in 2021 and told LJR that the Folha Editorial Manual “was our Bible.” In addition to studying the Manual to learn the guidelines for journalism produced by Folha, she also took classes with the newspaper's audience team and learned how to deliver content in a way that broadens the audience it reaches.

“There’s no way around SEO, for example. We had this in [training in] daily journalism; It wasn't just coverage, but also how to package it to have an audience, to be clickable, and to avoid clickbait. We had to provide headline options within the characters for the same article, thinking about SEO,” Gonçalves said.

The change in training content follows the change in supply and demand for journalism experienced by Folha. In 2023, Folha had the third largest average print circulation in the country: 41,000 copies, according to data from the Circulation Verifier Institute (IVC) compiled by Poder360. In 2017, this number was three times higher: Folha had an average circulation of 121,000 copies per day that year. Digital subscribers, which were 164,000 in 2017, reached 755,000 in 2023.

Estadão followed the same trend, but with a smaller drop: from 114,000 copies printed daily in 2017, to 56,000 in 2023. Digital subscriptions also grew, but at a slower pace than those of Folha: from 89,000 in 2017 to 193,000 last year.

Those in the class of 2024, which starts in April, will take classes in politics, economics, law, Portuguese, ethics, data journalism and multiplatform journalism, Miranda said. According to her, young journalists have arrived at the course with great ease in producing audio and video content and in understanding and using social networks to disseminate this content. The difficulty usually lies in how to integrate these different formats to produce and broadcast journalistic content, and this became part of the course, Miranda said.

“They know what's cool on TikTok or Instagram, without a doubt. That's not what I need to teach. What I need to teach you is how to use what you use in your daily life in such a brilliant way to create more powerful journalism,” she said.

Singer and Miranda agreed on the perception that one of the main points to be strengthened in people who come to the courses is journalistic writing itself. Both Folha's training and Estadão's course have emphasized text production in different genres and formats, such as reportage, interview, video script and podcast.

Furthermore, according to Singer, recent generations have come to training “more militant” and with some difficulty in seeking the other side.

“So it’s [necessary] to try to open [the trainees’] minds and say that not everything is right or wrong, good guy or bad guy. There are many things in between. So learn to listen even to people who you think are worthless, and value the counterpoint.”

Bianchi said that one of the most important things the Estadão course gave her was a network of friends who are also colleagues and help each other.

“You get to know, at once, 30 people, ideally from different parts of the country. So you already have contacts in places you wouldn't have [without the course]. (...) It is a very strong network, which I still consider an important network, and even with people who are not necessarily in my class there is a certain companionship, which I call mafia, that helps each other,” she said.

A negative point of her class on the Estadão course, Bianchi pointed out, was the lack of racial and regional diversity and the gender imbalance – the class was made up of 18 men and 12 women.

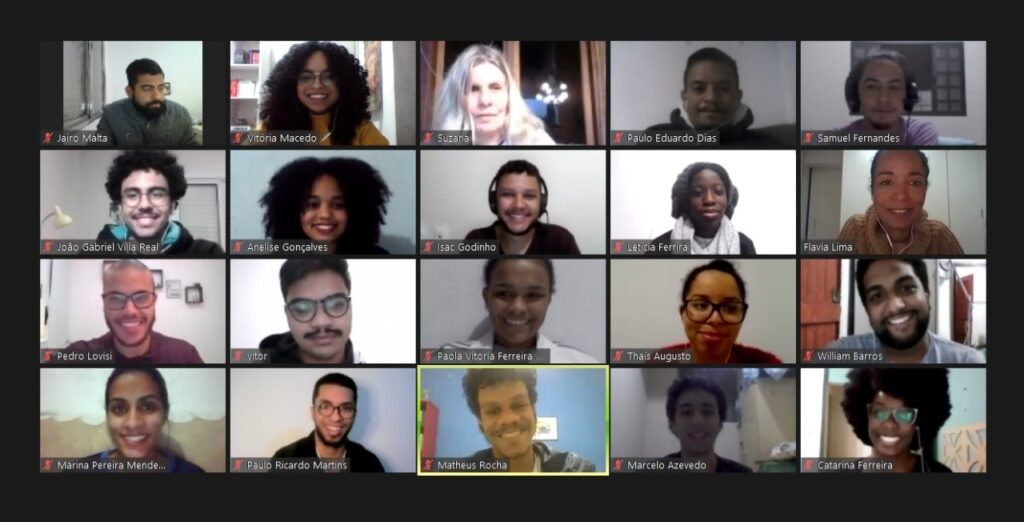

The "focas" of the 33rd class of the Estadão Journalism Course, held in 2023. (Photo: Daniel Teixeira/Estadão)

“I saw the photo of last year's class and saw a much more diverse class than the class I joined. So Estadão, at the time I studied, failed to look at this issue of diversity. Because the more diverse a newsroom is, the more interesting it will be; even the agendas will be more interesting,” Bianchi said.

The fact that it was a full-time course that did not offer remuneration or stipends also made access difficult for people who needed a salary to support themselves or who did not have savings to fall back on during the three months of the course.

Journalist Ana Cristina Rosa, now a columnist for Folha, was part of the 1993 class for Estadão's training course. She told LJR that she left Rio Grande do Sul, the state where she lived, to take the course, and managed to stay in São Paulo because she had money saved, had free accommodation at friends' houses and did freelance work during the course.

“I am a Black woman and the first person in my family to earn a higher education. I had no contacts or a way to reach a media outlet in the center of the country other than through my own efforts. I saw the Estadão course as an opportunity to learn a little about the market and show my ability to work for this market in São Paulo, in a major newspaper,” she said.

Rosa worked at Estadão for four years after completing the trainee course. She said she had two other Black colleagues during this period.

“At that time, this was a non-issue. (...) The idea of racial democracy was much stronger, and it was something like 'you made an effort and you're here. There just aren’t more people here like you because they didn’t make an effort.’ As if that were enough to gain space, which we know it isn’t,” she said.

In a study that analyzed the race and gender profile of people who wrote texts in the newspapers Folha de S. Paulo, Estadão and O Globo between January and July 2021, Estadão was the newspaper with the highest percentage of white people: 88. 7%. However, according to Miranda, “the newsroom scenario is currently not the course scenario,” as the last class had 40% Black trainees, she said.

Over the years, the selection for the course has also changed: instead of demonstrating their knowledge of English – something that in Brazil denotes belonging to higher classes – whoever applies for the course at Estadão will have to present an story proposal, defending the relevance of the report and explaining how it would be produced and in what formats it would be published. And, since 2022, Estadão has provided cost assistance to trainees who request this assistance, Miranda said.

In addition to these initiatives, Estadão is also developing a journalism course aimed exclusively at Black and low-income professionals, in partnership with Universidade Zumbi dos Palmares. The idea is to train professionals who can work in various areas within a media outlet, such as administration, marketing or human resources, said Miranda, who also coordinates this initiative. The course is in the fundraising phase and there is still no forecast for when registration will open.

Anelise Gonçalves and Suzana Singer on the last day of activities for the first edition of Folha's training program exclusively for Black professionals, in 2021. (Courtesy/Folha)

Folha held three editions of its training program aimed exclusively at Black journalists. Gonçalves participated in the first edition, which consisted of online classes between 6pm and 10pm. She took the Folha training while she was interning and finishing college, and said she was only able to participate because it was a 100% remote program, due to the pandemic. The online training made it possible for there to be people from various states in the country in the class, including her, who lives in Rio de Janeiro.

“It was a very positive experience. (...) If it were in person, I wouldn't have been able to stay [in São Paulo], but I think I would have a greater wealth of being able to interact with people. So, I sent messages and emails [to colleagues in the course and Folha journalists]. I have always been that person who talks, but if I had been physically in the newsroom the experience would have been richer,” she said.

In 2024, Folha's training program will return to being 100% full-time in-person. Singer said that “online is very democratic, it helps a lot to bring people in, but it doesn’t even compare” to the experience of holding the program in person in the newspaper’s newsroom. To try to maintain the regional and racial diversity from online programs when they return to in-person programs, Folha will offer scholarships to some of the selected people.

“We don’t have the financial means to pay everyone,” Singer said. “But we have reserved scholarships and we will have socioeconomic criteria to allow those who go through the selection process to be able to take the course.”