Narrative journalism is a tool to tell stories that are true, as defined by Argentine journalist Leila Guerriero in her narrative journalism workshops for the Gabo Foundation. Guerriero also says that this type of journalism serves to portray reality with literary tools, and that in this genre, the form of the text, the use of language and rhythm are elements as important as the story that is going to be told.

LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) spoke with three journalists who specialize in long-form narrative journalism: Mónica Baró (Cuba), Diego Fernández Romeral (Argentina) and Beatriz Valdés (Colombia) about best practices for producing features or crónicas of quality narrative journalism.

All three have received the Gabo Prize in the Text category for pieces that fall in that genre: Baró in 2019 for “The blood was never yellow,” Valdés in 2023 for “The cry for justice and reparation for Afro-Colombian women who were sexually assaulted,” and Fernández Romeral this year for “The night of the horses.”

Below, we present 15 recommendations from these authors for writing long-form narrative journalism pieces as memorable as their winning works.

From the journalists' trenches, the only thing that can keep narrative journalism alive is to develop an eye to detect stories that can really move people and allow them to question their opinions and beliefs, Fernández Romeral said.

“Learning to detect those stories that have so much complexity in themselves that they leave you in uncomfortable places, that produce emotions in you, will allow things like this [the success of ‘The night of the horses’] to continue happening,” he said. “This is how I think narrative journalism is sustained, finding the stories from our work as journalists.”

A good story of narrative journalism cannot be done at the speed of other journalistic genres, said Fernández Romeral, whose crónica “The night of the horses” took about a year to complete. Mónica Baró dedicated three years to investigating and writing “The blood was never yellow.”

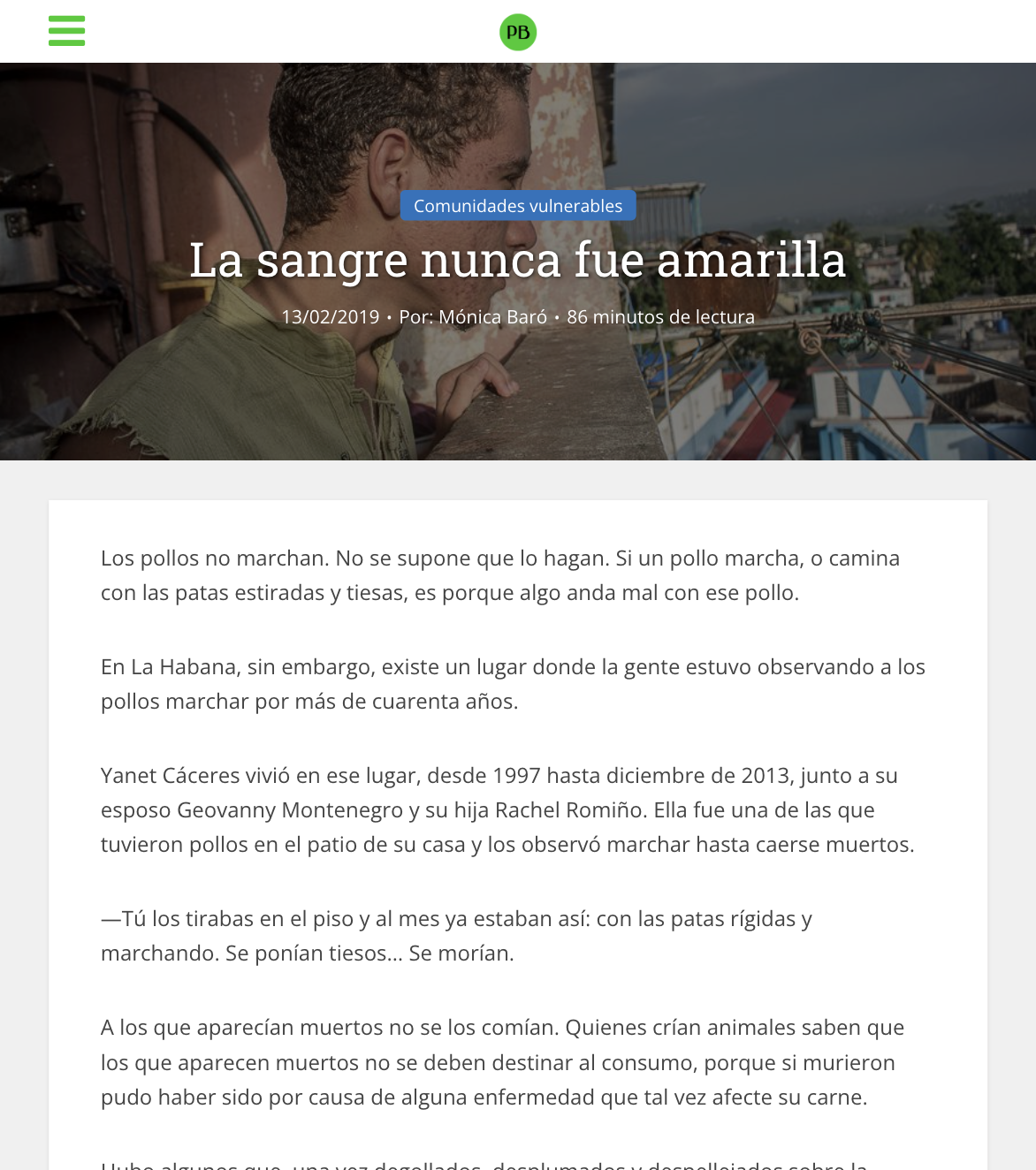

Baró's Gabo Award-winning report on lead contamination in a Havana community and its impact on the health of its inhabitants. (Photo: Screenshot from periodismodebarrio.org)

“There are stories that when you detect they can take months, you should choose one and give it all the time it needs. Don't hand it over until you have what you had in mind. Even if it's just one, let's give ourselves the pleasure of doing it that way," said Fernández Romeral, quoting Argentine journalist Javier Sinay, who also won the Gabo Award for "Fast. Furious. Dead: a Buenos Aires crónica.”

Baró said that in Latin America very few journalists have the ideal conditions to produce a long-term report. Therefore, you must be aware that doing so always involves giving up several things.

“The ideal circumstances don’t exist, much less if you are a Latin American journalist, much less if you are an émigré or living in exile,” she said. “Then it is simply a matter of choosing, betting on yourself and betting on a story.”

As in other genres, in narrative journalism the author's voice must be kept as neutral and as invisible as possible, Baró said. However, there are stories that allow the author's voice to be more present. Although there are no formulas to know in advance what type of language works best for each story, journalists should ask themselves the question before starting to write.

“I somehow avoid generalizing the same voice for all stories because I feel that all stories have their own soul and demand their own narrative. Not only with the language, but also with the structure,” Baró said.

Thinking about the narrative structure that the story will follow before sitting down to write it is very helpful, not only to avoid losing the thread of the narrative, but also to ensure that the story has the meaning you want to give, Valdés said.

“The structure is key for you to know where you’re going, but for me it is also key for you to feel that the story actually works and that it is not simply like a string of information in which one thing simply follows another.”

Defining a narrative structure involves assembling the stories that will make up the feature, configuring the chapters and arranging the scenes, once the reporting and the material used to tell it have been reviewed, Valdés said. In the case of her award-winning report, the journalist put together a narrative structure around a main character, whose story is the guiding thread of the narrative.

“It's like structuring at which moments complementary information enters, at which moment something that a source told you can enter that is related to or differs from what the main character told you,” she said. “It is knowing where the consistency of the story may be, or if they are perhaps a series of stories, what is the glue that unites them.”

Spanish allows a very different relationship with time than other languages when it comes to narratives, Baró said. This opens the possibility of playing with the structure of a long-form crónica so as not to necessarily present it chronologically.

“In the rationale of Latin America and the Caribbean, time is perhaps a much more diffuse element,” Baró said. “We are used to approaching stories not necessarily chronologically, but sometimes by something that suddenly shocks us and that's where we start. I try to play a little more with the structure.”

Although narrative journalism breaks with the rigid structures of other genres to give rise to aesthetic and literary elements, it is important that the author does not lose the journalistic objective of her work, Valdés said.

Therefore, the narrative must obey the information, and not the other way around, so that the message transmitted is clear, she added.

“Many times one is tempted to write in a literary and poetic way, but the idea is not understood. And if the idea is not understood, it is useless,” she said. “It is important that what is going to be communicated is clear. For me, journalism absolutely has to be of service. So if it doesn't work for you because you don't understand it, I think the objective is not being achieved.”

Adjectives must be used in narrative journalism very carefully, especially when a story addresses tragic or crude themes, Baró and Fernández Romeral agree. For the Cuban journalist, whose stories have addressed topics such as deaths, crimes and illnesses, using qualifiers to describe events can border on the morbid.

“The stories, what is happening with the characters, the events themselves already give an image of reality,” Baró said. “When the image is so well given by the facts themselves and they are also harsh images, it seems to me that the adjectives become too crude.”

Fernández Romeral said that he learned from journalist Julio Villanueva Chang, founder of the defunct Peruvian narrative journalism magazine Etiqueta Negra, that hard data must be linked to narrative images that help understand them based on something else.

The research and writing of “the night of the horses” took journalist Diego Fernández Romeral about a year. (Photo: Screenshot of gatopardo.com)

In the case of his story, which addresses the issue of illegal horse meat trafficking, so that the reader had an idea of the amount of money that this business moves in the world each year (US $500 million), the journalist compared it to the inheritance that Queen Elizabeth II had left her family.

“You should never fall into how tedious the data is or data overstimulation,” he said. “You have to give an image so the reader feels something, because a number does not convey emotions. The data is necessary because it is journalism, but we need that data to convey emotions.”

Journalists who aim to write a piece of narrative journalism must have a lot of patience and invest time to gain the trust of sources, ideally over several encounters. That’s especially true of sources in vulnerable conditions or who have experienced tragic events, Baró said.

Sometimes, the journalist said, the first interviews serve more to gain people's trust than to obtain information for the story.

“For me, the most relevant things do not arise in the first meetings. What interests me most is when people are less defensive and trust you more,” she said. “You have to get people to give you the words, the statements, the emotions that you are going to tell without the interviewee being conscious of it, which is attractive for literary journalism. That is a process that takes work and another series of strategies.”

Baró and Valdés agree that interviews for long-form features must be much more extensive than those required for other genres. In addition, it is important that the people you’re interviewing be in a controlled environment, where they feel calm and commit a good amount of time.

“These interviews require time, they require observation, they require paying attention,” Valdés said. “In my case [for the Gabo Award-winning story], the interviews were very long, they were hours of interviews.”

Baró said that for stories about sensitive topics it is particularly important for the journalist to ensure that she has enough time to dedicate to the interviews, so that the interviewees feel empathy.

“If you are going to ask a person who has been the victim of an attack, or who has lost a family member, and you ask them about that pain, about something so intimate, leaving after 10 minutes is a little disrespectful,” Baro said. “Hurrying can be understood as not caring.”

There is no payment that is enough to compensate for the time and effort put into the production of a long-form narrative journalism report, Fernández Romeral said. For this reason, he said, the ideal thing is to do these types of stories when you have the economic part resolved.

“If I had done ‘The night of the horses’ for the money, I would have had to finish it in a month, which is how long I would have been able to live with the payment for the crónica,” he said. "You have to make that decision to say 'even if it's one story, I'm going to do it just for the story.' When you find THE story, you know that you are going to give yourself to it, that you are going to dedicate everything it needs and that you are not going to do it for the payment, because the payment will never be enough.”

To write good narrative journalism, it is essential to read many pieces of the genre by different authors, the journalists agree.

But Baró goes even further. The Cuban journalist said that before starting a feature, she tries to dissect the texts of other colleagues to try to decipher how they were made.

“Before doing a story, I look for how a similar problem has been told and I try to go beyond reading it and try to deconstruct the reporting behind it,” she said.

Self-editing allows you to do an introspective exercise before the text reaches the hands of an editor, Valdés said. It also helps the journalist to identify the lack of necessary data, or if there’s too much information. Likewise, with a self-editing process you can know if the narrative flows correctly or if adjustments need to be made, Valdés said.

Valdés' piece takes the story of Aura, an Afro-Colombian woman who suffered sexual violence during the armed conflict in Colombia, as the guiding thread of the narrative. (Photo: Screenshot from elespectador.com)

“Suddenly you think that you wrote something beautiful but then you see that either it is not understood or it is actually information that is not necessary, or that, on the contrary, can confuse,” she said. “I think the self-critical eye is like the first great filter for you to be able to understand that your narrative is achieving its objective. And, on the other hand, so that later the external editing process is not so painful.”

To self-edit effectively, it is advisable to “let the text rest” for a few days and then return to it with fresher eyes, the journalist said.

Narrative journalism is not exempt from the need to verify the accuracy of information. To do this, follow-up interviews are important, Valdés said.

“Sometimes you are writing and realize that you are missing a piece of information and that piece of information cannot be ignored. It’s essential to be able to return to the source, to the protagonists, to ask more questions,” she said.

The journalist added that it is important to make sure sources are available so you can contact them in case you need to verify dates, ages, places, or other data that, if not available, would leave loose ends in the narrative.

“At the time of the interviews, you don’t know how important that data is going to be in the story, so I also believe that having the possibility of returning to the sources to verify is a fundamental point,” she said.

When you dedicate so much time to a narrative journalism feature, you should avoid thinking about issues such as how well readers will receive it, how many clicks it will generate, or whether it will win any awards, because that distracts the journalist from the goal of telling a good story, Fernández Romeral said.

“You have to work for the story. It is true that if you work for the story, then everything that happens comes on its own,” he said.