A nearly eight-year dream came true for Colombian journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima when, in June this year, congress passed a law creating a fund to prevent, protect, and assist women journalists who are victims of violence.

The fund was officially launched at an event last month that Bedoya described as a space created “for them”—women journalists in Colombia. Government representatives and female journalists from across the country attended, welcoming Law 2358, which formally establishes the fund.

The “No Es Hora de Callar” fund, or “This is not the time to stay silent” in English, was approved in compliance with an August 2021 ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. The court found the Colombian government responsible for violating Bedoya’s rights following her kidnapping, torture, and sexual violence on May 25, 2000, as retaliation for her journalism.

Bedoya Lima, currently gender editor of the El Tiempo newspaper, was kidnapped at the entrance of Bogotá’s Modelo prison in May 2000, while investigating the deaths of 26 inmates and an alleged arms trafficking operation inside the prison. During her approximately 10-hour abduction, she was tortured, beaten, and sexually abused. She was later abandoned some 80 miles (130 kilometers) away on a road near the city of Villavicencio.

Only three people have been convicted for the crime. The masterminds and other accomplices have not been identified.

“I envisioned this fund about eight years ago when we started drafting the lawsuit against the Colombian government,” Bedoya told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “It was something I always felt needed to be created because, when these events occurred, I had no support, and it was incredibly difficult to find anyone who had my back. I don’t want other women journalists to go through that.”

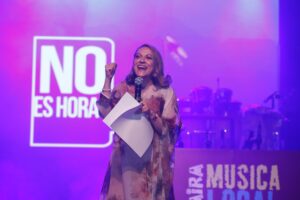

Colombian journalist Jineth Bedoya Lima during the celebration of the 15-year campaign No Es Hora de Callar on Sept. 23, 2024. (Photo courtesy Néstor Gómez / Casa Editorial El Tiempo)

Of the 13 measures ordered by the human rights court in its ruling, five hold special importance for Bedoya as she personally crafted them to protect not only her rights but also those of all women journalists and victims of sexual violence.

The court also called for the creation of the “No Es Hora de Callar" Memory and Research Center. For Bedoya, this is perhaps the most significant measure, as the center will document the history and memory of sexual violence, as well as freedom of expression and the work of women journalists in Colombia.

Bedoya said the fund is not intended to allocate resources for protection measures, such as relocating journalists or responding to emergency situations, as Colombia already has a protection mechanism for this. Instead, its resources—$500,000 U.S. per year for five years, according to the Foundation for Press Freedom—will be used for prevention and research programs.

In collaboration with the center, the fund will focus on academic research that can eventually serve as a foundation for strategies and policies to combat the various forms of violence faced by women in media.

However, the fund will also support ongoing investigations by women journalists who are at risk because of their work.

“We want them to have the tools to move forward with their projects and not self-censor due to threats, intimidation, or lack of support," Bedoya said.

Bedoya is leading several processes to implement the fund's regulations, with participation from the Bogotá-based Foundation for Press Freedom, or FLIP for its initials in Spanish.

Jonathan Bock, FLIP’s executive director, called the creation of the fund a significant step, to address the many difficulties regional journalism faces, particularly with a focus on supporting women journalists.

Bock underscored the 15-year-old “No Es Hora de Callar” campaign, founded by Bedoya, which has identified the work of women journalists in different parts of Colombia. With the fund, they now have greater support and promotion.

However, Bock expressed concern that it took three years after the court ruling to implement reparations.

He said he believed the government complied because of Bedoya’s persistence.

“That can also raise questions about whether it’s the victims or those entitled to reparations who have to bear the burden of leading all of this,” Brock said. “This was really Jineth doing the leading.”

For him, the lessons learned in the process of enforcing the ruling are important for overcoming bureaucratic hurdles and truly finding justice.

Colombian journalist Claudia Julieta Duque, who has been fighting for justice since 2001 following psychological torture by state agents, called the fund’s creation an important first step in addressing and specifically protecting women journalists from violence.

In July 2001, Duque was kidnapped, marking the first direct attack against her for her investigation into the murder of Colombian journalist and comedian Jaime Garzón in 1999.

And from 2001 to 2004 faced a series of direct threats, surveillance, and harassment, which Colombian courts recognized as "aggravated psychological torture" committed by agents and high-ranking officials of Colombia's now-defunct intelligence department. Given the lack of justice in her case, she presented it to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2018.

“It’s commendable that Jineth and her mother, Luz Nelly Lima, turned their case into a positive action for all the country’s journalists,” Duque told LJR.

“For now, with a contradictory government and a president who offends and stigmatizes us, I remain skeptical," she said.

According to organizations like FLIP, the relationship between the press and President Petro has been "tumultuous.” In one of the most controversial incidents, on August 30, the president referred to female journalists as “mafia dolls.” After the backlash, Petro took to his X account, stating, “When I speak of establishment journalists, I’m referring to those who don’t serve the public, but rather work for dark powers.”

“It is contradictory and paradoxical to receive this law from a government that, less than a week ago, called women ‘mafia dolls,’ that two months ago called a journalist a Mossad journalist, and less than three months ago accused FLIP of being an ally of paramilitarism and a friend of drug traffickers. These are the same epithets that were used against us, that were used against me 20 years ago by an entirely different government,” Duque said when the fund was launched.

Bock said he also found it ironic that, on a day meant for celebration, the discussion had to address the president’s repeated criticisms of journalists, especially women. In response to the president referring to women journalists as “the mafia’s playthings," FLIP filed a lawsuit alongside the independent organization El Veinte late last month on behalf of 19 female journalists.