Koos Koster, a 46-year-old Dutch journalist, arrived in El Salvador in March 1982 at the request of the Dutch television company IKON.

His assignment: to make a documentary contrasting life in San Salvador and rural areas where the conflict between the country’s Armed Forces and the FMLN insurgent group was taking place. Koster was joined by producer Jan Kuiper, sound engineer Hans teer Laag and cameraman Joop Willemsen, all of Dutch nationality.

The 12-year civil war in El Salvador, which would eventually end with the 1992 Peace Accords, began just two years before. Salvadoran authorities knew about the journalistic project Koster was leading and viewed it as being favorable to the FMLN guerrillas, according to a report from the Truth Commission.

Koster, who spoke Spanish and had contacts in the region, hadn’t gained much sympathy among Salvadoran authorities due to a report he did in 1980 on the so-called death squads, which authorities also felt favored the FMLN.

The Truth Commission report says that, for this reason, intelligence police monitored the Dutch team producing the documentary. Eventually, officers ordered an ambush by state forces and the four journalists were murdered along with guerrillas who acted as their guides, the report concludes.

It has been 42 years since the murders and no one has been brought to trial. However, the advance of two judicial processes, one civil in the United States and another criminal in El Salvador, could mean someone is punished for the crime.

“Their deaths have marked the lives of the bereaved,” Gert Kuiper, Jan's brother who is leading the civil lawsuit in the U.S., told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) through a lawyer for the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA).

“For me personally, making a point – the formal acknowledgement of plotting the murder and punishing those responsible – is essential,” he continued.

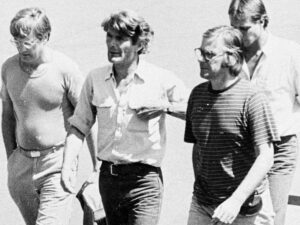

Jan Kuiper, Koos Koster, Joop Willemsen and Hans teer Laag were the four journalists who were killed in 1982 in El Salvador. (Photo: Comité de Prensa de la Fuerza Armada)

Los cuatro periodista holandeses asesinados en 1982 en El Salvador había llegado al país a realizar un documental. (Foto: Comité de Prensa de la Fuerza Armada)

The U.S. case is against former Colonel Mario A. Reyes Mena, commander of the Fourth Infantry Brigade, whom the country’s Truth Commission report says planned the ambush. Now 85 years old, he has been living in the U.S. for more than a decade.

Meanwhile, in one of the most important advances in El Salvador in the journalists’ murders, on Aug. 22, a judge determined a separate case could advance to the trial stage. It’s a decision that became final after the Santa Tecla Criminal Court rejected an appeal presented by the defense on Oct. 22.

Three former high-ranking military commanders accused of being responsible for the murders of the four journalists are being prosecuted: former Minister of Defense, José Guillermo García; former director of the Treasury Police (a type of intelligence police), Francisco Antonio Morán; and the former commander, Reyes Mena. Two other people named in the incident have died.

“It would be very important for us because it is historic,” Oscar Antonio Pérez, director of Fundación Comunicándonos – an organization that represents the families of the journalists in El Salvador together with the Salvadoran Association for Human Rights (ASDEHU), told LJR.

“It is the first case that appears in the Truth Commission report that is going to be tried and it is the first case where high-ranking military commanders who were precisely part of the past conflict are going to be tried. It is very important to break this chain of impunity,” he added.

The events that preceded the murders of the journalists and the murders themselves are recorded in the Truth Commission's report “From madness to hope: the 12-year war in El Salvador” published on March 15, 1993.

The report includes interviews the communicators had with prisoners suspected of being guerrillas, as well as with FMLN contacts. It also points to the monitoring of the journalists, and even how their hotel rooms were searched the day before the crime.

The Truth Commission concluded that “there is complete evidence” that the murders of the journalists “were a consequence of an ambush previously planned by the Commander of the Fourth Infantry Brigade, Colonel Mario A. Reyes Mena, with the knowledge of other officers.” The report says that the ambush was based on intelligence work and was carried out by a patrol of 25 men from the Atonal Battalion under the command of Sergeant Mario Canizales Espinoza (deceased).

Despite the information collected by the Truth Commission and the commitments negotiated in the Peace Agreements that established reparation measures for all victims of the civil war and the establishment of a Transitional Justice system to judge the crimes committed within the framework of the conflict, the approval of the “General Amnesty Law” on March 20, 1993 prevented those accused of the crime from being tried.

It was only until 2016 when the country's Supreme Court declared this law unconstitutional that some crimes committed during the war began to be prosecuted. In March 2018, the criminal suit in El Salvador was filed, but as Pérez said, the prosecutor's office took its time and did not bring the case before the courts until 2021.

For two years, two of the accused have been in preventive detention, although they are serving it in a hospital citing health problems. Reyes Mena is in the United States with an extradition order in force.

When Jan Kuiper's family learned that Colonel Mario A. Reyes Mena had been in the U.S. for more than a decade, they contacted the Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) to obtain representation in the country to file a civil lawsuit, said Claret Vargas, senior lawyer at the CJA.

The case was investigated for several years in order to file the suit on Oct. 9 before a U.S. District Court in Alexandria, Virginia, Vargas told LJR.

Taking into account that the U.S. allows only civil lawsuits against U.S. residents who committed crimes in other jurisdictions, this lawsuit seeks monetary compensation, as well as a recognition of responsibility for the crime. However, its main objective is to achieve some impact on the criminal process being carried out in El Salvador, Vargas said.

In an unrelated case involving another crime, former Minister García lost a civil lawsuit in the U.S. and was extradited to El Salvador, Vargas said. Lawyers hope that something similar will happen with Reyes Mena.

“That’s always the hope, but we have no control over what the immigration authorities are going to do nor is there a legal means by which we can ask for that,” Vargas said. “Obviously what we would hope is that it contributes to the case there because at the end of the day our job is to contribute to the efforts to combat impunity in the country where the crime was committed.”

The legal process in the U.S. does not have a clearly defined timeline. Taking into account the actions of the defense and decisions of the judge in charge of the case, it could take up to a year to see a judgment.

Though the long wait is worrying, Gert Kuiper said these cases are especially about setting precedents for justice in crimes committed during the war.

“It's not about the 3 men getting long sentences. They are very old. The interest for the bereaved families is that they will be held accountable and that justice will be done,” Gert Kuiper said. “When the criminal case finally occurs in El Salvador, jurisprudence can be built so that 200 more murder cases related to the aforementioned war can be heard.”

Pérez, however, said that the inevitable passage of time for victims and perpetrators could deepen impunity.

“The problem is that our victims are dying. And the perpetrators are also dying without being held accountable,” Pérez said.