Two Brazilian media outlets dedicated to local journalism have embraced generative artificial intelligence to grow the impact of their work and automate tasks that demand precious time and effort from their lean teams.

Agência Tatu and Farolete are native digital media outlets that have developed projects that combine data scraping and ChatGPT technology to produce content based on public data.

Tatu, headquartered in Maceió, capital of the state of Alagoas, features local and regional reporting, covering the entire Northeast region. Farolete is dedicated to covering the municipality of Ribeirão Preto, in the state of São Paulo, Southeast Brazil.

“Local journalism has not yet adopted artificial intelligence and projects in this aspect of technology to assist in daily work,” Lucas Thaynan, visualization director at Agência Tatu, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “This is already in the big newspapers, which have greater capacity and a larger technology team, but we have shown that, even with a small team, we can carry out projects that can have a positive impact. It’s a cool experiment to show other [local] outlets that it’s possible to do something along these lines.”

Founded in 2017, Agência Tatu is the first media outlet specialized in data journalism in Northeast Brazil. And SururuBot, its first initiative with generative artificial intelligence, was launched in October 2023 to produce weekly texts publicizing open job vacancies in Maceió.

Lucas Thaynan, visualization director at Agência Tatu. (Photo: Courtesy/Agência Tatu)

“We wanted to somehow use artificial intelligence to create stories. We decided to focus on job openings due to numerous factors. One of them is that we had the data available in a structured way. (...) Another important point is that we wanted a project that would not be stashed away, that few people would access. We wanted something relevant to society,” Thaynan said.

The SururuBot project was financed by the Acelerando Negócios Digitais (Accelerating Digital Business) program, promoted by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and Meta, a company that owns social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. The Digital Journalism Association (Ajor, for its acronym in Portuguese) was one of the media associations supporting the initiative.

The bot works in two steps, as Thaynan explained. The first step is automation, which does not involve artificial intelligence: the Tatu team created a script, a sequence of commands in the Python programming language, to collect and process data on vacancies available on the National Employment System (Sine ) that refer to Maceió.

Article written by SururuBot and published at Agência Tatu's website. (Screenshot)

In the second stage, the processed data is delivered to the bot created based on GPT-3.5 technology, from the company OpenAI. GPT technology, which stands for Generative Pre-Trained Transformer, is a language model that uses machine learning to generate text in human-like language. It's the same thing that drives ChatGPT.

“We did post-training to explain the format, the language, the structure of the text that we needed [the bot] to deliver. It was an arduous stage, because we did a lot of training to reach the expected result,” Thaynan said.

This technology generates text based on data on job openings available that week and sends the content directly to the publisher of the Agência Tatu website. Publication, however, is not automated: a team member reviews the text, checks the information and, if necessary, makes changes, and then publishes the post manually.

“All content on SururuBot undergoes human review. This is essential,” said Thaynan, who said that artificial intelligence is “a fundamental aid” for journalists and that anyone who does not work with it “will be left behind.”

“Why have a journalist every week reporting on job vacancies? Let's put this to a robot, for artificial intelligence to do this boring work, and let's let the journalist do something more complex. Artificial intelligence will not be able to carry out in-depth investigations or relevant interviews. So the role of the journalist is fundamental,” he said.

The team at Agência Tatu. (Photo: Courtesy/Agência Tatu)

For Thaynan, media outlets that want to start using artificial intelligence in their processes must develop a technology use policy.

“We had this concern before launching SururuBot, because this usage policy gives us parameters and limits on how we should work with this new form of technology. (...) We have to provide transparency to our readers about how we produce content and also internally, the team can understand how they can work [with AI],” he said.

Farolete, a one-man project by Cristiano Pavini, is run by the journalist during his time off, he told LJR. After seven years working as a reporter for local media outlets, Pavini went to work at an NGO at the beginning of 2019. However, his desire to do journalism did not fade, and in October 2019 he founded Farolete as “an initiative for the purposes of exercising journalistic practice”.

“I run Farolete alone, and I only produce reports that are of public interest. I don't chase clicks and I don't go after sensationalism. I only do stories that I understand have some relevance for contextualization and impact purposes,” Pavini said.

The journalist said that he felt the need for automated monitoring of bills filed and voted on by the Ribeirão Preto City Council, both to help him carry out reports and to make this information available to the public in a more accessible way.

Journalist Cristiano Pavini, founder of Farolete. (Courtesy)

Just like Agência Tatu with SururuBot, Pavini entered his project in the Accelerating Digital Business program and was selected. He ended up inviting Tatu to develop the technology that resulted in FaroLegis, launched in November 2023.

The FaroLegis process is similar to that of SururuBot, as it also involves two distinct steps, automated data scraping and text production with GPT-3.5 technology.

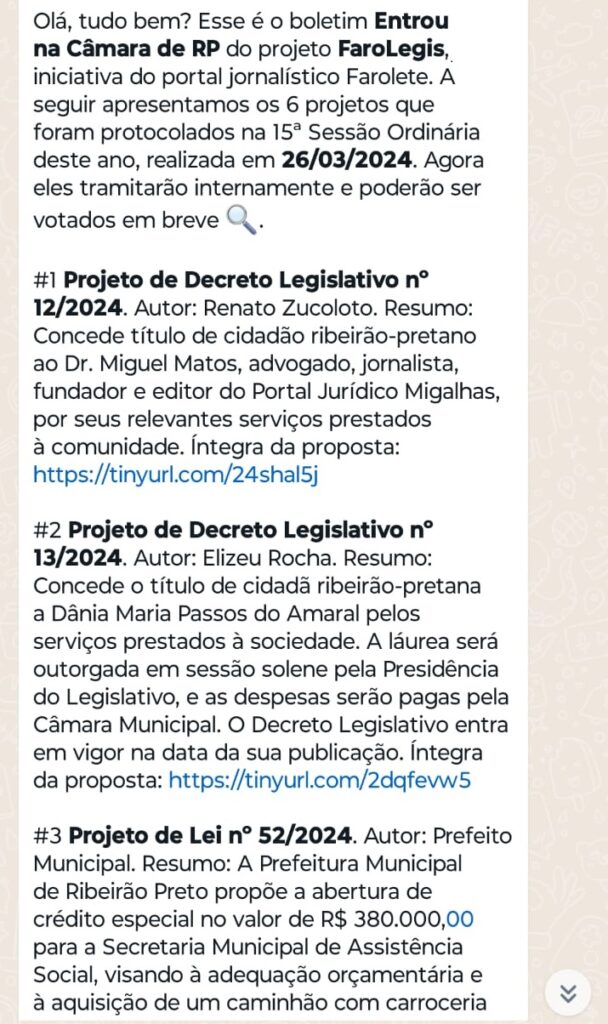

Two bots collect the content of bills filed and voted on at the City Council, available on the Council's website as PDF files. The bots send this data to a generative artificial intelligence model programmed to summarize each bill in 300 characters in a standardized text template already formatted for sending via WhatsApp. The texts are sent by the bots to Telegram, as this application is easier to integrate with the technology used, Pavini said.

The journalist then reviews the texts and forwards them to two WhatsApp groups, one with people interested in the registered bills, who receive the newsletter “Entrou na Câmara de RP” (Entered the RP Council), and another with people interested in the bills that have been voted on, who receive the newsletter “O que a Câmara votou ontem” (What the Council voted on yesterday). These two groups, together, total about 100 people, Pavini said. They emerged from another WhatsApp group managed by the journalist, where he distributes articles published on the Farolete website and other content developed specifically for the messaging application, and which has around 1,200 people, he said.

“The Council has two sessions, every Tuesday and every Thursday. So every Wednesday and every Friday I send two automated newsletters. (...) Of the automatically generated newsletter, I keep 90 to 95% [of the content]. I make one or two aesthetic adjustments. It doesn't tend to hallucinate, because we created a series of commands for GPT” to prepare the text according to the desired parameters, Pavini said.

One of FaroLegis' newsletters on WhatsApp. (Screenshot)

The journalist said that, before developing the initiative, he passed a questionnaire among the participants of the Farolete WhatsApp group to understand what they considered important to include in the newsletters. Then, he sent the links so that interested people could sign up to receive them. According to him, “key actors in society” joined the group, such as members of the Brazilian Bar Association (OAB), members of the commercial and industrial associations of Ribeirão Preto and members of public servant unions.

In addition to enabling citizens to stay informed about the activities of the City Council, FaroLegis also assists Pavini in covering the municipal Legislature.

“For me it's interesting because I'm able to monitor the Council, understand what is being voted on, what is being filed, what the profile of the projects is, without having to go to the Council's website, which is what I did when I was local media journalist. Twice a week, I went to the website and read all the projects, and now FaroLegis summarizes them for me. And when I see that it is something of greater relevance, I will see the project in its entirety”, he said.

A project he learned about through FaroLegis was the Municipal Education Plan (PME) filed by the city of Ribeirão Preto in the Council at the beginning of December. Pavini analyzed the project and published an article about it.

“Some of the points I raised [in the article] were addressed in councilors’ amendments later,” he said.

FaroLegis is available free of charge to the public because the idea, for now, is to reinforce the Farolete brand, monitor it and produce content from it, Pavini said. In the future, he intends to sell this technology as a service to interested institutions.

“If someone wants to monitor whether education is being debated in the Council, I can calibrate the robots for that,” he said.

Pavini said he was “a great enthusiast” of artificial intelligence applied to journalism.

“It is a great ally and cannot be something that is restricted to large media outlets,” he said. “This project of mine shows that. It is an independent local initiative, just five years old. I run Farolete alone and it has a certain recognition in the city. And I managed to use AI in a product that has helped me in my journalistic practice and resulted in a product for my audience. And eventually it could be a product that I can monetize.”