International and national recognition could not spare Mexican journalist María de Jesús Peter Pino or her family from the endemic violence against the press in Mexico, which has left at least 140 professionals murdered since 2000.

In two years, she went from winning the Ortega y Gasset Journalism Award from Spanish newspaper El País, to living in exile in the United States due to death threats against her and journalist husband Juan de Dios García Davish.

Pino and Davish are two of four Mexican journalists who tell their stories in the new documentary “Estado de Silencio” (State of Silence). For doing their work, they have been subjected to threats, attacks, forced displacement and exile. Even so, they maintain their commitment to journalism and the public’s right to information.

“As journalists, we tell stories. We have to tell ours,” Pino told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) regarding her participation in the documentary, which was screened publicly for the first time in early June at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York.

Mexican documentary filmmaker Santiago Maza directed and co-produced the film, which was made by production company La Corriente del Golfo, from Mexican actors Diego Luna and Gael García Bernal.

Maza told LJR that the 83-minute film is a Mexican view of a global problem.

“Talking about journalism and the problems that cause journalists to suffer violence is talking about all problems,” Maza said. “The documentary talks about organized crime, disappeared people, violence against migrants, exploitation, corruption, impunity. All these problems are very inherent to the reality of Mexico today.”

Pino has worked as a journalist for more than 25 years and specialized in covering migrants in the city of Tapachula, in the state of Chiapas, on the border between Mexico and Guatemala. Davish, her husband, is general director of the Quadratín Chiapas news agency, and Pino is deputy director of the agency and correspondent for the newspaper El Universal. She says in the documentary that the two share a passion for reporting based on denunciations and with a focus on human rights.

Over the years, they have repeatedly been targets of attacks by public authorities and threats from organized crime. One of them, reproduced in the documentary, was received by Davish in a phone call from a person who identified himself as a commander of the Los Zetas cartel. The alleged commander says that members of the criminal group will invade Davish's house and take his family. These threats were repeated until, in mid-2022, the couple decided to leave the city where they were born and lived and to go into exile in the U.S.

María de Jesús Peter Pino and Juan de Dios García Davish during their exile in the United States. (Scene from the documentary 'State of Silence')

The documentary shows Pino and Davish's life in exile and the anguish they felt about being in a strange country against their will. It also accompanied Pino on her return to Tapachula, in mid-2023, where she and her husband are currently, she told LJR.

“I would prefer to not be [in the documentary], but I think it's a way to show what we do and what we face,” she said.

“It is important that society knows what many journalists do, especially in the provinces,” she added. “We are the ones who send the articles published at the national and international level, we put the issue on the table and we work under very deplorable conditions. We are poorly paid, we don't have social security, sometimes they don't pay attention to us. We are very forgotten.”

Other journalists followed in the documentary are Jesús Medina, in the state of Morelos, in the central region of the country, and Marcos Vizcarra, in Sinaloa, in northwestern Mexico. They also had to temporarily leave the cities where they worked due to death threats.

Maza said that the documentary shows how these four journalists were, during filming, at various points along the path of what it means “to be a critical journalist in Mexico: being threatened, secluding themselves after the threat, and finding ways to continue doing the work, but with resilience and adaptation.”

The director said that it is necessary to rescue the “human connection” between journalists who report information and the people who receive it, and that “returning to the human” in journalism is one of the lessons he learned while producing the documentary.

“Information has become anonymous, like something that happens by itself. Everything is on the phone and you see the information and you forget that there is someone who is experiencing the situation and therefore reporting it,” Maza said.

He said that many journalists also experience what they are reporting on, as is the case of the professionals shown in the documentary.

“It is not free for journalists who live on the border to talk about the immigration crisis, for journalists who live in the northeast of the country to talk about the disappeared and the violence carried out by cartels and organized crime groups, or for people who live next to where there are natural resources to talk about the exploitation of natural resources,” he said.

“We, as citizens, have to take responsibility for giving journalism a face, for humanizing journalism, and realizing that we depend on journalists to understand what is happening to us.”

The documentary “State of Silence” highlights the role of Mexican governments in violence against journalists, from the institution of the “war” on drug trafficking, during the administration of Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), to the current government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018- 2024) and its campaign to stigmatize the press.

Former governor of Mexico City Claudia Sheinbaum won the presidential election in June and will be the country's next president. A member of the same party as López Obrador, Morena, Sheinbaum is expected to take office on Oct. 1.

In a recent interview, she said she will do “whatever is necessary to protect journalists.” However, she rejected the conclusions of an Article 19 report on violence against press professionals and said she disagreed that “there was no attention to victims” during the López Obrador government.

Maza said he does not believe that a simple change in the presidency will improve the reality of Mexican journalists. However, he stated that the documentary was deliberately released at this “pivotal moment” during which it may be possible to influence priorities for the next president.

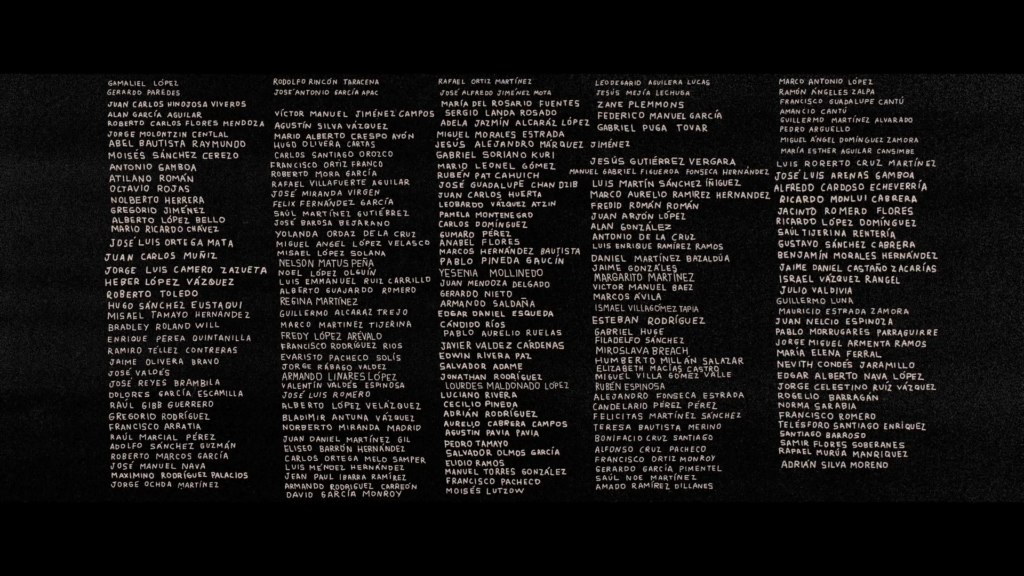

Names of journalists murdered in México appear in the credits of the documentary 'State of Silence'

It’s time to “be very incisive” and to forge alliances between journalists, media outlets, citizens and institutions inside and outside Mexico and put pressure on the new government to give due attention to the problem, he said.

Pino, in turn, said she had no hope of improvement for journalists in Mexico.

“I don't see hope for a change because we are talking about a party that I believe handed us over to organized crime,” she said.

Back in her hometown, she said it was no longer possible to work as she used to.

“Chiapas is convulsing. It is taken over by organized crime. I'm working, but I can't do the jobs I did before. I entered Indigenous communities, I worked on forced displacement, on the migrant issue, that is, they were strong issues, but I could still enter places to talk about certain things. Now it is not possible, we are really silenced,” she said.

According to Maza, public screenings of the documentary are planned for festivals and events in the coming months in Chile, Argentina, Mexico and Colombia. It should also premiere in some theaters on the commercial cinema circuit in Colombia, Mexico, Spain and the United States, and will be available on streaming platforms in October.

He said he hopes the documentary jolts the public out of apathy – “a spiral that is taking over and normalizing violence for us” – and towards empathy with journalists working in the country.

“If we manage to humanize the journalist so that people get involved with the problem, I believe that is the role of the documentary,” Maza said.

Pino said the documentary is “a magnificent work” and that the country’s journalists must make it theirs.

She also hopes that people will stand in solidarity not only with journalists, but also with the vulnerable people who appear in the reports that journalists are being threatened for, such as mothers searching for their disappeared children, migrants fleeing poverty and violence and the activists who defend their communities.

“I don't want them to tell me 'you're brave, you're great.’ The only thing I want with this documentary is for society to see the situation we go through as journalists to bring the information to the comfort of your phone, your television, the radio,” Pino said.

“We [the journalists in the documentary] are visible now. So don't leave us alone. Do not abandon us. Let them join this demand for justice for my colleagues who can no longer demand it today because they have already been silenced.”