From analog to digital, virtually all media organizations have followed a one-way route. But Paraguay’s outlet El Surti is doing the opposite. Since April, the investigative outlet has been publishing a print version of its most impactful stories.

Its first issue featured an investigation on pollution in the metropolitan area of Asunción. The second focused on the production of cement and lime. And the third told the story of a town that went nearly six months without sleep thanks to the noise from a bitcoin farm. This July, they are publishing a fourth edition on how the western region of Paraguay has become a major logistical hub for drug trafficking.

“Our print edition represents a couple of years of evolution in El Surti’s work,” co-founder Alejandro Valdez told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “We realized the key is not necessarily reaching the most people, but reaching the right communities, the right people who can influence the issue at hand.”

El Surti’s print edition looks like a small magazine with an average of 50 pages. The cover stands out with an illustration by a different artist in each edition, and the inside pages feature text, images and graphics that collectively tell a story.

This is not the first time El Surti has experimented with print. The outlet has also published collections of its best stories and books. For example, in 2023, they released Ruido (“Noise”), a book based on an investigation into disinformation during that year’s elections in Paraguay.

The difference this time is that El Surti’s print edition is a monthly publication, which allows them to maintain regular contact with their audience.

Each El Surti print edition has been launched at an event with music, drinks and interactive activities. (Photo: El Surti)

The print edition also represents a new source of income at a time when digital-native media outlets are facing challenges to financial sustainability.

To receive El Surti’s print edition, readers must pay a monthly subscription of 60,000 guaraníes, or about U.S. $8. If they pay annually, they receive a 16 percent discount. The service is only available in Paraguay and can only be ordered over WhatsApp.

Valdez said they currently have 100 subscribers and plan to reach 500 so it becomes a sustainable revenue source representing at least 10 percent of the outlet’s annual revenue.

“We are going to publish 10 issues this year. In terms of sustainability, it is currently an investment and part of a broader strategy,” he said.

El Surti is covering the costs of the print edition using its own funds and some grants it has received to boost the impact of the team’s stories, Valdez said.

El Surti’s mission and vision is to do journalism that inspires civic engagement, Valdez said. Part of the outlet’s strategy has been to step away from the screen — “to speak without algorithms or cookies,” he said, and hold in-person gatherings.

Each print edition has been launched at an event with music, drinks and interactive activities like a mural of the cover that attendees can help paint, or a table with rough drafts where subscribers can create their own designs.

“Many of those who joined my team at the launch party were already familiar faces. We've met them in events we've held in the past,” co-founder Jazmin Acuña wrote on LinkedIn after the launch of the first edition.

She added: “These gatherings reassure us that we have power to bring people together…We can nurture trust, spark curiosity, strengthen communities around information and remind everyone—ourselves included—that journalism can be a source of joy.”

Mauricio Maluff, a local university professor, was one of the first subscribers to El Surti’s print edition. He has followed the outlet’s investigations since the beginning and, on one occasion, even offered to make a donation to help support independent journalism.

“For journalism to work and be independent, it needs funding somehow, and that money should come from the readers themselves and not depend on outside power,” Maluff told LJR. “I went to one of the events they organized and it’s beautiful to build community around journalism.”

In the era of artificial intelligence (AI), where automated image generation is becoming common, El Surti is also betting on hand-drawn illustrations.

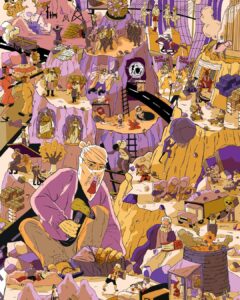

May print edition cover for the investigation “Una de cal y otra de miseria” (One of Lime and Another of Misery) included several references about the exploitation of bodies and resources. (Photo: El Surti)

Each print edition has featured a cover without a headline, where the illustrations take center stage and tell their own visual story.

Since El Surti’s founding, visual journalism has been a fundamental part of its work. So much so that its graphic style has earned awards such as the Gabo Prize for Innovation in 2018 and the Global Youth & News Media Prize in 2019.

In 2020, the outlet also created Latinográficas, a learning and collaboration community for journalists, designers and illustrators aimed at boosting the visual storytelling of news in Latin America.

“Illustration is not just a supplement, but rather a part of the journalistic process,” Jazmín Troche, visual editor at El Surti, told LJR. “While the investigation is being carried out, we are already thinking about the cover. Our main idea is for it to convey a message, to invite the viewer to pause, to look with intention and to tell necessary stories.”

The reporters behind each investigative story are invited by the illustrators to take part in the creative process for the cover. Each month, a different illustrator designs the cover and is responsible for creating an average of 30 visual references — whether from Indigenous art, pop culture, literature or cinema — that relate to the report.

For example, the May print edition cover for the investigation “Una de cal y otra de miseria” (One of Lime and Another of Misery) included several references about the exploitation of bodies and resources: the treasure hunt in the Paraguayan film “Empty Cans,” unemployed workers resorting to striptease in the film The Full Monty, Rafael Barret’s chronicle on slavery in the yerba mate fields of Alto Paraná and the video game Minecraft.

Troche explained that given the large number of visual references, readers might feel lost. That’s why they decided to include a game at the end of each print edition that invites readers to discover the references on the cover. The game, inspired by classic paint-by-number activities, presents the cover in black and white with each element numbered. On another page, a detailed explanation of each number and its meaning is provided.

“We conduct in-depth research to ensure the references make sense with the text,” Troche said. “It’s not just about having a beautiful cover, but rather the idea is also to create discomfort through beauty, to represent injustices, to create a tool that serves the community.”