The closing of the annual figures confirmed a trend that was looming with the murder of every journalist: 2022 became the deadliest year for journalists since 2018, according to the records of both Unesco and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

The 86 murders recorded by Unesco's Observatory of Murdered Journalists represented, moreover, a 50% increase in these crimes compared to the previous year. In other words, a journalist was murdered every four days. The figure also meant "a dramatic reversal of the positive trend" of decrease in these crimes highlighted by Unesco since 2018.

The questions were inevitable: what could explain an increase of this magnitude? And what is needed to combat this increase?

For Guilherme Canela, head of Unesco's Freedom of Expression and Safety of Journalists section, explaining this increase - which he calls "a disgrace" - requires academic and judicial investigations, as well as monitoring by the United Nations and Special Rapporteurs. However, he explained to LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) that those who analyze this issue have put forth some hypotheses.

According to Canela, one of these hypotheses has to do with a harmful environment for freedom of expression in previous years. In spite of the "positive trend" of a decrease in the murders of journalists, they [Unesco] had also been warning about the different attacks on freedom of expression in general and journalists in particular. They recorded, for example, the increase of attacks in the digital world - especially online violence against women journalists -, violence against journalists during social protests and "narrative violence against journalism" by political and religious leaders.

Aunque la violencia letal contra periodistas estaba a la baja, organismos como la Unesco venían alertando sobre un aumento en otros tipos de ataques: uno de ellos la violencia digital.

"One of the hypotheses is that we were already monitoring that, although there was a drop in murders, other types of violence were on the rise, so it was not that there was a calm environment for journalism. There were fewer murders, but other types of crimes or attacks [increased]. Perhaps what happened in 2022 is that these other types of attacks, this harmful environment against the press, translated into more murders," Canela said.

Other hypotheses - which are not mutually exclusive - have to do with the war in Ukraine and the pandemic. Coverage of the Ukraine war, which by 2021 did not exist, left 11 journalists killed. On the other hand, 2020 and 2021 were COVID-19 pandemic years that led to many journalists spending time in isolation, doing online coverage and generally reducing their physical exposure.

"Journalists went back to the streets, they covered more protests, they covered more of what had happened in the post-pandemic world and there the risks — including the risks of assassinations — grew again," Canela said. "But I insist. These are some of the hypotheses we’re working with to try to explain that, but more research is needed to understand exactly what happened, why this spike in 2022."

For Mexican journalist and security expert Javier Garza, the increase in murders in 2022 could be explained by two factors: the loss of respect for the value of freedom of expression and the high rates of impunity. According to Garza, the creation of different information bubbles has increased polarization and, in turn, intolerance towards those who have different opinions.

"Obviously that doesn't mean that intolerance has to lead to violence, but the probability of it leading to it increases," Garza told LJR. "We've seen it in some places. For example, in the case of the United States, [we see] acts of violence against journalists that maybe 20 years ago we couldn't conceive of because certain values like freedom of the press were accepted. When intolerance grows, the likelihood grows that some people who are intolerant will resort to violence".

In addition, high rates of impunity create the perfect scenario for an increase of these attacks. "We see that impunity encourages attacks. Every attack happens because the previous one went unpunished," Garza said. "Anyone who now thinks of attacking a journalist to silence him or her can be reasonably sure they will get away with it, because the person who did it the previous time got away with it."

Indeed, Unesco points out the issue of impunity as a problem to be solved immediately. According to its figures, impunity for crimes against journalists remains at 86%. “This proves that combating impunity remains a pressing commitment on which international co-operation must be further mobilized,” Unesco said in a statement.

Unesco figures show that the vast majority of journalists’ murders took place in not-at-conflict countries, although the number of murders in countries in conflict rose during 2022. Unesco found among the possible causes: reprisals for covering organized crime, armed conflicts or the rise of extremism; as well as coverage of issues such as corruption, environmental crimes, abuse of power, and protests.

Vigilia en Chile exigiendo justicia por la muerte de la periodista Francisca Sandoval, ocurrido en 2022. (Foto: Londres 38, espacio de memorias)

As has been the case for several years, Latin America and the Caribbean became the deadliest region for journalists. Mexico, with 19 cases, and Haiti, with nine, topped the list in the region. Colombia (with four cases), Brazil (with three, including the murder of British journalist Dom Phillips), and Chile (with the case of journalist Francisca Sandoval, the first murder recorded after the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet) are some of the countries in the region where murders were also recorded.

CPJ figures concur that 2022 was the deadliest for journalists since 2018, and that Latin America and the Caribbean was the most dangerous region. According to the organization, 67 cases were recorded worldwide, 30 of them in Latin America and the Caribbean.*

"More than half of the killings happened in just three countries — Ukraine (15), Mexico (13) and Haiti (7) — the highest annual numbers CPJ has ever recorded for those countries," the organization said in a statement. "Notably, despite countries across Latin America being nominally at peace, the region exceeded the high number of journalists killed during the war in Ukraine."

In Haiti, covering gang violence, the political crisis and social unrest triggered by the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021 became dangerous assignments. According to CPJ, at least five journalists in that country were killed in the course of their work and it is investigating two other deaths in which members of the police were responsible.

"Along with the criminality and humanitarian emergency in Haiti, the region faced a growing crisis of journalist killings, creating 'media deserts' and contributing to the insecurity of local communities," CPJ added.

The case of Mexico continues to be cause for concern in the region. Annually, it leads the rankings for crimes against journalists and impunity. 2022 was not only no exception, but for CPJ the number of murders was the "highest ever in a single year in that country."

For Garza, the situation in Mexico is "complicated" especially because the arrival of Andrés Manuel López Obrador to the presidency of the country was received with "much hope" that this problem would be addressed, and that they would seek to combat impunity.

"He was a public figure who for years talked a lot about the value of freedom of expression and talked a lot about corruption and the rottenness of the institutions and so on. But it turns out that when he came to power, he set the problem aside. Not only did he not attack it, but on many occasions he even took away resources from the tools that existed to attack it," said Garza, alluding to budget cuts to the Federal Protection Mechanism, to mention just one example.

Moreover, there’s a hostile discourse towards the press. "Although in the case of the president so far it has been verbal, he can set an example for many people who are at lower levels to say 'the president quarrels with journalists, and so do I.'"

What Garza mentions is one of the points that Unesco has been stressing for years: the need for a real commitment on the part of the State [in each country] to combat these crimes.

Canela explained that within the framework of the tenth anniversary of the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, they were able to observe that countries that saw a reduction in violence were those where there was a "coherent and integral implementation" of a three Ps policy: Prevention, Protection and Prosecution.

In places where one policy prevailed over another, results could be seen, but they were generally temporary or insufficient.

Canela also highlighted a key aspect in this search for solutions: to make society understand freedom of the press as an individual right, but also as a collective right.

"When a journalist is killed, everyone loses. It is not 'only' — in quotation marks — this journalist or his or her family," Canela said. "If society does not understand that, it will hardly support more resources, more investment, and a sustainable policy of prevention, protection and procurement of justice."

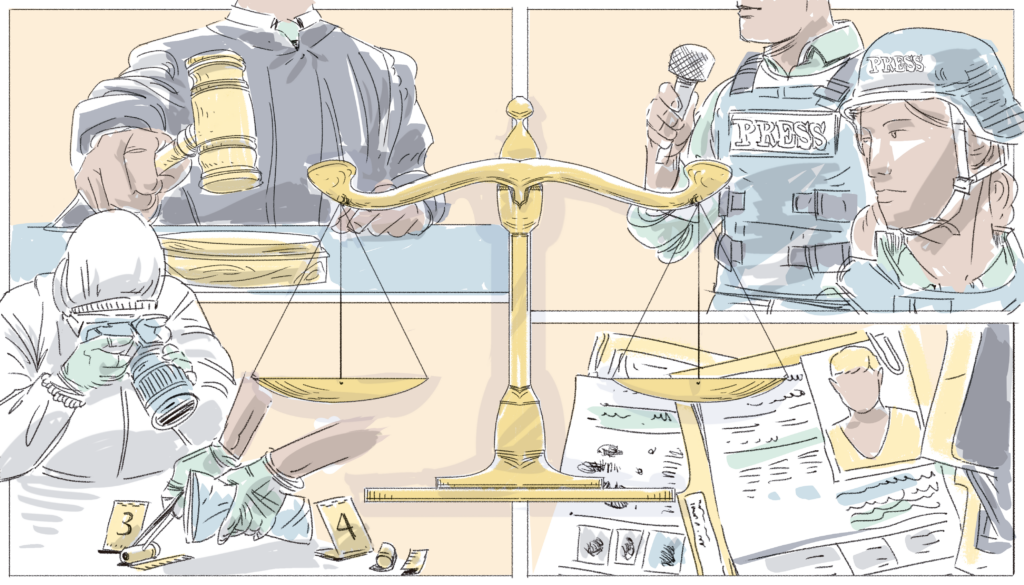

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez - Altais)

The central axis of this more pedagogical approach is to make society as a whole — which includes judicial bodies, government, parliament — see "what these attacks on an institution that is so central to democratic protection mean for a society." There must be "an effort to intensify this dialogue on how we can collectively confront this problem, even though the primary responsibility for protection is the responsibility of the State," Canela said.

Finally, both Canela and Garza believe that one can never have too many self-care measures. Garza emphasizes two aspects: the importance of ongoing training and the creation of networks or collectives to provide support.

"[Networks] where we can rely on other colleagues to share experiences, to learn from them, to help us denounce, so that in those collectives we can also forge links with international organizations such as Article 19 or CPJ," Garza said. "That also helps a lot because it helps above all to make visible the risks faced by journalists in a particular place and to put the authorities on notice that they have a pending job there."

In addition to safety training, Canela gives a special piece of advice: "don't keep quiet." "Looking at possible security risks, investigate crimes against colleagues from a journalistic perspective. That is very important. Do investigative journalism on these issues," Canela said. "And of course, keep denouncing, keep asking for justice and adequate public policies."

*The figures for murders of journalists tend to vary among organizations because they use different methods for recording them.