Almost 150 million Brazilians are eligible to vote in the November elections this year, during which mayors and council members will be elected in more than 5,500 municipalities of the country. To better the journalistic coverage and quality of the public debate at this crucial moment for any democracy, the Instituto para o Desenvolvimento do Jornalismo (Institute for the Development of Journalism, or Projor) and the Institute of Education and Research (Insper) launched the Manual GPI Eleições 2020 (2020 GPI election manual) in early august.

The project offers ample material, which is at the same time technical and didactic, with the main concepts, tools and tips on how to cover the next election and local public policies. The site has more than ten sections: Municipalities, Policy, Transparency, Data, Superior Electoral Court (TSE), Ethics, Fact-checking, Impact, Questions, Videos and more.

Manual GPI Eleições 2020. Photo: Print screen

“We joke that if a reporter were to come from mars, know Portuguese, and read the manual, he would be able to get by the elections. We made a project thinking in all the citizens, but above all the local journalists, because they are the ones that can question the candidates,” Angela Pimenta, who is the editor of the project and director of operations of Projor, told LatAm Journalism Review.

In each of the site’s sections, there is a concise introduction and practical tips that include how to write headlines without reinforcing misinformation, how to use dozens of free tools for data journalism, how to fact check and verify photos and videos and even how to measure the impact of the stories.

The TSE section, for example, explains the rules of the elections: who can be a candidate, how the electoral calendar works, the latest changes in legislation and the profile of the electorate. There is an entire section with lists of technical questions to ask candidates, divided by topic (education, health, environment, etc.). The Municipalities section, on the other hand, teaches the role of the mayor and council members, and how municipal taxes and revenues work.

Pimenta states that the journalistic coverage about the candidates ends up being, many of the times, based more on the politician’s personality, and the manual helps to support a more technical debate. "We want to fill a gap with reliable, available, robust and friendly information for the local journalist, because it (the site) has everything there, including references, links, it's a toolbox. The reporter is tired, running late, sometimes he doesn’t know the subject, because it’s outside of his beat, so he can open the questions [in the manual, before going to cover the event]. The idea was to help those who need it,” she explained.

One of the main sections, the Policy section, shows the most important acronyms, goals and challenges in education, housing, the environment, mobility, health and public safety. It also indicates, for each of these areas, what are the responsibilities of the local, state and federal powers, in addition to critical issues and the best sources. Sections such as Impact, Ethics, Data and Fact-checking go far beyond elections and can serve as practical guides for journalism at any time.

The manual’s first edition was released for the 2016 elections and integrates the Grande Pequena Imprensa (Big Small Press, or GPI) project, created by Alberto Dines, the journalist and founder of Projor. The second edition was done in partnership with Insper to make the site more comprehensive. In addition to Pimenta, the project is edited by journalists Francisco Belda and Pedro Burgos and economist André Marques.

Angela Pimenta. Photo: Personal archive

It took over a year for all of the materials to be created and almost 30 professionals participated, in their majority journalists, academics and specialists. The Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) and the Pólis Institute are institutional supporters, and funding comes from the Google News Initiative and the Facebook Journalism Project.

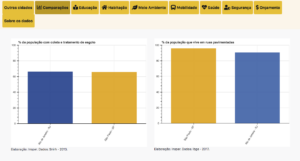

In addition to the content for consultation, the site offers a tool called Raio-X dos Municípios (x-ray of municipalities), which was developed by Insper. The platform is a compilation of different public databases, in which it is possible to search for information about each municipality and compare it with others.

Thus, when choosing a city, the user visualizes a series of numbers, such as the average time of commuting from home to work, provision of hospital beds, percentage of the vaccinated population, access to electricity and basic sanitation, and more. All of these indices are presented with context and graphs, which can be compared to the national average, and with five other municipalities in the same region with similar populations, Human Development Index and economy.

According to Pedro Burgos, project editor and coordinator of Insper's Advanced Program in Communication and Journalism, the tool facilitates the reporter's work, because it brings together information that is dispersed in many databases.

"Not everyone has the time to take a course in data journalism or the ability to extract a million-line CSV (raw spreadsheet file), which is necessary to work with data from municipalities. Sometimes, when you download the spreadsheet [from a public database], the column names are confusing, and you need to have a data dictionary, it's a laborious process. The goal was to make it more accessible," he told LJR.

Burgos states that Raio-X dos Municípios will continue to be updated, even after the elections. He hopes the project will serve as both an educational tool and as reference material not only for reporters, but also for journalism students. This would be important because, according to him, colleges do not usually train journalists to cover public policies.

"There is a deficiency in training at this point, so we are unable to judge what an effective public policy is. We think that putting more money into a problem means helping to solve it, but that is not necessarily true. If you look at the headlines in Brazilian newspapers, a common news article is 'the government only spent 20% of the budget for such a thing.' And this [smaller spending] is considered a failure," he said.

He gave an example about different municipalities that received federal funds to face the COVID-19 pandemic. "When you look at the data, a municipality spent more because it bought 30,000 hydroxychloroquine capsules, which has no effect [against the disease]. So for the journalist to have this slightly more sophisticated view, of not just looking at spending, but measuring the impact, he needs to have better training in public policies," he said.

Raio-x dos municípios, Manual GPI Eleições 2020. Photo: Print screen

Burgos believes it is a global trend to have weaker coverage at the local level. In Brazil’s case, the reason for this is, besides the journalists’ training, because of the lack of engagement and interest of the population in local policies, which is reflected in a lower audience for these articles.

“A policy story has more interest and engagement if it talks about Brasilia, about [Jair] Bolsonaro’s administration, because it is treated as a soap opera, everyday there is a new chapter. It is normal for journalists to write those stories, because we, as readers, we like drama, and there is more of that on the national level. Congress is more dramatic and dynamic than a city council, for example,” he said. With that, Burgos said, there is no incentive from newsrooms or from readers to cover local policies in depth.

That is something that the project wants to reverse, because, according to Angela Pimenta, the local power is the closest and most visible in the life of the people. “Those decisions made by the city hall directly affect the daily life of the people: if there is a hole in the street, if there is no lighting, if the line at the clinic is too long... And yet, in terms of news, this has less coverage. We know more about the Planalto Palace than our city hall."