By Sara Mendiola*

This is the fourth article in a series about the investigation and persecution of cases of violence against journalists in Latin America.**

(Illustration: Pablo Pérez - Altais)

On March 23, 2017, journalist Miroslava Breach Velducea was murdered as she was leaving her home in the city of Chihuahua, in northern Mexico.

Breach was a reporter for newspaper Norte in Ciudad Juárez and a correspondent for La Jornada of Mexico City. In the months prior to her murder, she had published several reports on links between local authorities and drug trafficking groups and she was one of the few journalists who documented the displacement of Indigenous communities in the Sierra Tarahumara due to the penetration of criminal groups.

She was hit with eight shots from a 38-caliber pistol. The details of her work, particularly her revelations about criminal groups operating in the state of Chihuahua, necessitate that her journalistic work must be at least a hypothesis in the motive for the crime. The first investigations carried out by the Chihuahua State Prosecutor's Office indicated this, since the first statements by local authorities pointed to the fact that it was a "narco-political" crime.

But months later, the local Prosecutor's Office changed its tone and ruled out the participation of political actors or officials and pointed only at a criminal group, according to the case files obtained by Propuesta Cívica, a non-profit dedicated to the legal defense of journalists, as part of its work advising Breach’s family.

The local investigators fell into a contradiction about their versions, but both of the two versions pointed to journalistic work. Even so, the specialized institution that the Mexican State created to prosecute attacks against journalists did not consider it necessary to take on the case at the federal level.

The Special Prosecutor for Attention to Crimes Committed against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE, for its acronym in Spanish) was created in 2010 in response to the increase in attacks, particularly murders, against journalists.

A mural in Culiacán, Mexico, remembers slain journalist Javier Valdes, cofounder of the local weekly RioDoce (Photo courtesy of newspaper Noroeste)

Located in the then-Attorney General's Office (Procuraduría General de la República), the objective was to shield the investigations of crimes against journalists from local authorities, who are often accomplices.

The FEADLE had been created precisely to prevent state prosecutors from falling into contradictions such as those exhibited by the Chihuahua Prosecutor in the Miroslava Breach case. Also to avoid the opacity that followed, because in the 10 months after the crime, the local Prosecutor's Office denied the journalist's family access to the investigation, arguing they were not indirect victims of the crime.

But the continuous requests to FEADLE to claim the case and take control of the investigation were ignored despite the context of the crime.

The family of Breach Velducea had to go to a federal judge for him to order the local Prosecutor's Office to recognize the relatives as indirect victims, since this would allow access to the investigation and participation in the process. Even so, the Chihuahua Prosecutor's Office refused to comply with the court order. It took a year after the homicide for FEADLE to decide to take on the entire case.

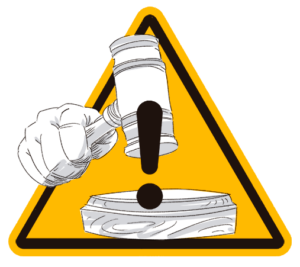

The tomb of journalist Miroslava Breach in the city of Chihuahua constantly has flowers and a banner against impunity in crimes against journalists. (Photo courtesy of Red de Periodistas de Juárez)

The investigation in the hands of the federal government achieved the first sentence against one of the perpetrators, and the hypothesis of the crime’s motive was confirmed: Breach had been assassinated for her investigations. This was evidenced in the trial against Juan Carlos Moreno Ochoa, the first person arrested for the crime.

Moreno was arrested in December 2017, nine months after the murder, and identified as the intellectual author of the crime. His trial began in March 2018, and there various witnesses specializing in criminal investigation exposed how narco-politics operates in the Chihuahua mountains and the possible involvement of politicians of the local government in the crime.

In addition, Federal Judge Néstor Pedraza Sotelo stated in his conviction that in the trial it was proven that Breach was the victim of homicide as a result of her journalistic investigations.

Two years had to pass for the next arrest. On Dec. 17, 2020, the Special Prosecutor's Office arrested Hugo Amed Schultzfor his probable participation as an assistant in the homicide. Schultz was mayor of Chinipas, a municipality in the Sierra Tarahumara, where Breach had investigated the presence of drug cartels.

On June 15, 2021, the former mayor accepted the facts of the accusation and his criminal responsibility and was sentenced to eight years in prison.

The history

Mexico was one of the first countries to create a special prosecutor's office to investigate crimes against journalists. The first version of the FEADLE was the Special Prosecutor for the Attention of Crimes Committed against Journalists (FEADP), created in February of 2006.

One of the initial problems that this new Prosecutor's Office had was that the agreement that created it did not establish a definition of journalist or a methodology to determine what was considered "professional exercise" to establish it as a motive for an attack. This allowed the Prosecutor's Office to establish a narrow definition and declare itself incompetent to investigate most of the crimes before establishing if there really was a connection with journalistic work.

Another problem was that the FEADP was limited to federal crimes and crimes punishable by imprisonment, thus leaving threats or aggressions outside its jurisdiction.

The FEADP lasted just four years and by 2010 it was clear that it had not worked. In the four years before the creation of this Prosecutor's Office, 10 journalists were murdered. In the following four years, there were 32 killed.

For 2010, the Rapporteurship for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, in its 2010 Special Report on Freedom of Expression in Mexico, spoke about the lack of results from the Prosecutor's Office.

“The office has not made any impact on reducing the generalized impunity that holds sway in cases of violence against journalists, if we consider that according to information provided in the course of the on-site visit, since its creation in 2006 the FEADLE had not achieved a single conviction, and had brought only four cases to trial,” the report said.

In that report, the Rapporteurship already recognized the transformation of the FEADP into the FEADLE, which was created in August 2010.

However, the new Prosecutor's Office maintained the ambiguities regarding the definition of “journalist” or “journalistic activity” to justify its intervention. This caused an increase in the declarations of lack of jurisdiction, the motion of the Prosecutor's Office not to intervene in a case. And although the law gives the victims or their relatives the recourse to fight the declaration of a lack of jurisdiction before a court, the resolution of a judge can take from six months to a year, which affects the investigations, especially the collection of evidence.

Cases of success and failure

The case of Miroslava Breach has been considered an achievement by FEADLE, along with the arrests and sentences obtained in the case of journalist Javier Valdez Cárdenas, who was killed in Sinaloa on May 15, 2017, less than two months after Breach's murder.

But both cases are exceptional because of the way in which FEADLE took on the investigation after pressure from groups of journalists, civil organizations and international organizations that defend freedom of expression.

Javier Valdez's case was unusual because on the same day of his assassination, then-President Enrique Peña Nieto announced that FEADLE would take up the case. Peña Nieto was reacting to the public outcry for the crime against one of the most internationally awarded Mexican journalists, recognized for his coverage of organized crime.

A memorial in Culiacán, Mexico, mourns journalist Javier Valdez after his murder in May 2017. (Photo courtesy of newspaper Noroeste)

The case of Javier Valdez was the only one that merited such an intervention by the Mexican president. Peña Nieto did not do so with the 31 murders of journalists that occurred before May 15, 2017, nor with the 15 that followed until November 30, 2018, when he left the government.

Even with the extraordinary intervention of the president, the investigation of the Valdez case was slow to produce results. Two years after the crime, the Rapporteurs for Freedom of Expression of the UN and the IACHR questioned the slowness of the investigations.

There are several cases that show how FEADLE ignores attacks on journalists, including murders. A couple of examples are the murder of Armando Saldaña Morales and the attempted murder of Indalecio Benítez Mondragón.

In November 2013, Indalecio Benítez founded the community radio station Calentana Mexiquense, in the municipality of Luvianos, State of Mexico. This is the so-called “Tierra Caliente” zone, near the limits of the state of Guerrero, a region with a strong presence of drug cartels, which control everything from poppy planting to business extortion. Less than a year after founding the radio station, on Aug. 1, 2014, upon arriving at their home, Benítez and his family were assaulted by several armed men who shot at the car they were traveling in. One of Benitez's children, a 12-year-old son, died.

Benítez filed a complaint with the FEADLE, which began the investigation, but more than two years later, the Prosecutor's Office determined that there was no evidence to link the attempted murder of which he was a victim with his journalistic activity, and so it declined to take the case and sent it to the Attorney General's Office of the State of Mexico.

An evaluation from Propuesta Cívica found that FEADLE's actions were not aimed at identifying those responsible, nor establishing a link with his journalistic activity. Due to the foregoing, in 2017 Benítez and Propuesta Cívica filed an injunction to restore the authority of the FEADLE. A federal judge considered that the Special Prosecutor did not take the necessary actions to establish the link between the crime and Benítez's journalistic work and ordered it to retake the case, which was never resolved.

There are other cases in which FEADLE does not intervene at all.

Two years later, in the same area of Tierra Caliente, near where Benítez's family was attacked, another reporter was killed. Nevith Cortés Jaramillo worked at a news portal that published citizen complaints. On Aug. 24, 2019, he was stabbed to death and the crime is still unsolved.

In the Tierra Blanca area, on the borders of Veracruz and Oaxaca, Armando Saldaña Morales worked in radio and newspapers. He was an announcer for the stations KeBuena and Radio Max and a contributor to newspapers such as El Mundo de Córdoba and Crónica de Tierra Blanca.

On May 2, 2015, he was abducted as he was leaving his office in the municipality of Acatlán, in the state of Oaxaca. Two days later his body was found with four gunshot wounds and signs of torture.

Among the issues that Saldaña was investigating at the time of his death was the illegal theft of gasoline from ducts owned by state-owned oil company Petróleos Mexicanos. It’s an activity controlled by organized crime.

The original investigation was assumed by the Oaxaca Attorney General's Office for the crime of homicide. Propuesta Cívica asked FEADLE to exercise its power to take on the case due to the probable link between the homicide and his journalistic work, but on Sept. 10, 2015, without having analyzed the case or carried out investigations into Saldaña's work, the then-Special Prosecutor Ricardo Nájera Herrera, declared that he would not take on the investigation, according to the follow up of the case done by Propuesta Cívica. To date, the case remains unpunished, the alleged perpetrators remain at large.

Power of “attraction”

FEADLE's main weapon to investigate crimes against journalists that fall within the sphere of state authorities is the so-called "power of attraction," or assertion of jurisdiction. The Mexican Constitution states that federal authorities can take on crimes from the local level when they are connected to federal crimes or in the case of "crimes against journalists, people or facilities that affect the right to information."

The National Code of Criminal Procedures presents a series of scenarios that merit the power of attraction by the federal Prosecutor's Office, but even so it is presented as optional and in case of refusal, the only option for the victim is to resort to a federal judge, which means a long and complex process.

One of the reasons FEADLE was given the power of attraction was the possible involvement of state or municipal public officials in the attack on a journalist. Removing the investigation from the state sphere reduced the risk of impunity. But if this weapon is not used, the local authorities are the ones in charge of the investigations and in most cases there are officials involved.

According to the FEADLE Statistical Report 2010-2021 obtained by LJR, of the 312 people against whom FEADLE has filed criminal proceedings, two thirds (204) are public servants, and of these the vast majority (190) are from state or municipal governments, including a governor and eight mayors. 141 of them are police officers.

Journalists protest outside the office of the Chihuahua state Attorney General to demand justice in the murder of reporter Miroslava Breach. (Photo courtesy of Red de Periodistas de Juárez)

In recent years there has been an apparent paradox with the Prosecutor's Office: it has suffered budget cuts, which in 2022 was just over 14 million pesos, about US $700,000, but at the same time it has given the best results in its history.

Eighty-five percent of the convictions have been obtained in the last four years, but this number can be misleading because in reality in its entire history from 2010 to 2021, the FEADLE has only obtained 28 convictions. Six of them have been for homicides, just a small fraction of the total murders of journalists in Mexico between 2010 and 2021, which is 96. That is, just one in 16 homicides of journalists has ended with the perpetrator(s) sentenced.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has recorded the murder of 11 journalists between January and June 2022. However, only one of those cases, that of Heber López, assassinated on Feb. 12 in Oaxaca, has been taken on by FEADLE. In the rest of the cases, the Prosecutor's Office had not even initiated investigations to determine if the crimes were related to the journalistic work of the victims.

LJR sent interview requests to Prosecutor Ricardo Sánchez Pérez del Pozo for comments on the work of FEADLE, but there was no response.

Violence against the press has increased since the year 2000. The majority of those journalists killed or attacked for their professional practice present two patterns that exemplify the situation in the country, explains Víctor Martínez Villa, a lawyer who has accompanied cases before the FEADLE as coordinator of the legal area of Propuesta Cívica.

“The first is that at the time of the events, the journalists who were murdered or attacked were mostly investigating topics related to drug trafficking, politics, corruption, violence and insecurity. The second, that the murders and attacks on journalists are in severe impunity,” Martinez told LJR.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has pointed out that there is "generalized impunity" regarding cases of violence against journalists, even regarding the most serious acts such as murders and disappearances.

But attempts to create prosecutors' offices to combat impunity for these crimes have not borne fruit. The first test (the FEADP created in 2006) lasted just four years. Its replacement, the FEADLE, has lasted more than a decade, but with mediocre results.

The sentences obtained in the last period, 2018-2021, are mainly for the crimes of homicide, abuse of authority, threats, torture, against the administration of justice and injuries, according to the FEADLE 2010-2021 report.

But the Prosecutor's Office hides behind the figure of "declaration of incompetence" to evade investigations, determining that it does not have the power to intervene, according to Martínez. In 2014, there was an accelerated increase in preliminary investigations, which coincides with the highest number of declarations of lack of jurisdiction, according to the 2018 FEADLE Report. Between those years, of the 803 preliminary investigations that it knew of at that time, it declared itself without authority in 442, more than a half.

FEADLE was created alongside the Mechanism for the Protection of Journalists, established in 2012, two years after the Prosecutor's Office model was changed. But the Mechanism has also presented deficiencies.

“Herein lies the problem of impunity. If FEADLE and the state prosecutor's offices worked properly, there would be no need to have a Protection Mechanism,” Martínez Villa said.

*Sara Mendiola is the director of Propuesta Cívica, a non-profit dedicated to the legal defense of journalists, based in Mexico City.

**This is the fourteenth report in a project on journalist safety in Latin America and the Caribbean. This LatAm Journalism Review project is funded by UNESCO's Global Media Defense Fund.

Read other articles in the project at this link.