From 2018 until June of this year, the Military Police of the State of Rio de Janeiro killed 7,848 people, equivalent to 27% of the violent deaths in the territory of 16.5 million people, according to data from the Institute of Public Security (ISP, for its acronym in Portuguese). Some of these deaths occur when police officers have the right to use force; for example, in the face of an imminent threat.

Other cases, however, present strong evidence of extrajudicial executions, as reported to the UN by several NGOS in 2020. These are situations in which, for example, the dead are often shot in the back or at close range, and then evidence is removed from the scene before forensic examinations can be carried out.

Journalist Rafael Soares, from newspapers O Globo and Extra in Rio de Janeiro, has made covering these incidents his speciality. His primary focus is on investigating incidents such as executions carried out by police officers, the process by which officers become contract killers, and even the emergence of large criminal organizations within the police force, all as part of his coverage of the field of public security at large.

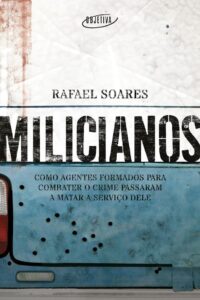

The journalist has just published his first book, “Milicianos: Como agentes formados para combater o crime passaram a matar a serviço dele” (Militiamen: How agents trained to combat crime began to kill in its service) through the publisher Companhia das Letras. In the non-fiction work, he recounts and analyzes various cases in which law enforcement agents in Rio de Janeiro became corrupt to the point of becoming gruesome criminals, forming organizations comparable to the mafia known in Brazil as “militias.” These groups dominate extensive territories in the city and state of Rio, charging illegal fees to those working in all kinds of services, from merchants to transportation services to construction companies.

In Soares' book, police brutality and corruption within the force go hand in hand. The police officer who least respects their ethical and technical obligations and resorts to violence more often, who tortures and kills more, is precisely the one who will have fewer qualms about embracing dishonesty and illegality more fully.

"This idea emerged from an interview with anthropologist Luiz Eduardo Soares [no relation] and contradicts the notion popularized by the film 'Tropa de Elite' (Elite Squad). In the film, you have police officers who torture but still do their job, and those who are corrupt and don't work. But in reality, as Luiz Eduardo told me, both things go hand in hand. Lethality [the capacity to kill] operates precisely within a logic of corruption," Soares said in an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

"The guy who kills a lot is also the one who sells himself for a higher price. That's how it works on the streets, and that's also the police I know. In the lives of these characters in the book, this happened on an absurd scale."

Journalist Rafael Soares working in the newsroom of O Globo and Extra newspapers (Photo credit: Courtesy/Domingos Peixoto/Agência O Globo)

Today, at the age of 32, Soares stands as one of the country's leading reporters specializing in public security. However, when he initially embarked on his journalism career as a student at the School of Communication at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, his aspirations centered on covering the inner workings of political power in Brasília.

Market circumstances led him to the metro beat, and from there, he made the shift to journalism focused on public security. In late 2012, as he was nearing graduation, Soares was interning at Infoglobo – the parent company of newspapers O Globo and Extra, with the former being a national publication and the latter a more local and popular one. Infoglobo served as one of the main entry points for journalists in Rio de Janeiro.

Fábio Gusmão, who was then the head of metro and police beats at Extra, and whom Soares describes as “an editor with the soul of a reporter,” convinced him to take a position as a rookie reporter at the newspaper. Soares's first police story for Extra was initially supposed to be about a public transportation-related construction project. However, based on a tip from a worker at the site, he returned to the newsroom with a scoop about militias in the West Zone of Rio. The article was published on Dec. 8, 2012.

"I had no police sources, no family connections to the police, and I didn't know how a police station operated. And then I wrote this story, and Gusmão liked it a lot," Soares said.

Since its inception in 1998, Extra had a strong focus on human rights and on exposing cases of police corruption, Gusmão told LJR. This, in the view of the journalist who is now the editor-in-chief of the newspaper, defied a prejudice often associated with popular newspapers, that they would uncritically echo official narratives.

"Addressing human rights issues has always been one of the newspaper's core principles, as has exposing police corruption. As a reporter, I myself covered dozens of corruption cases, abductions, and embezzlement, especially within the PM (Military Police). This became a trademark," Gusmão said. "Because we also report on facts related to productivity, some may mistakenly think we're pro-police. But that's a misconception. An incorrect image has been formed in that regard."

Gusmão's approach to the beat, as he explains it, aimed to treat police-related topics as one facet of public security: a domain influenced by politics, with a broad repository of specialized expertise, spanning areas like prevention, the legal system and basic rights.

"One needs to have a comprehensive understanding. I have always advocated for work based on data and investigations. It's essential to grasp that everything has an origin," Gusmão said. "And Rafael specialized in this. He understood that it was necessary to study and comprehend the logic of public security."

The case of the construction worker Amarildo, who disappeared after being taken from his home in the Rocinha favela by police officers in 2013 and was never found (eight police officers were convicted of torture, murder, and concealing a corpse) marked Soares' first major story. Collaborating with reporter Carolina Heringer, who also specializes in public security, Soares published over 60 articles on the case throughout the years.

"Extra had a somewhat distinctive approach compared to most major Brazilian newspapers, which I always kept in mind. We would continue revisiting cases until they reached a resolution, and we placed great importance on that," Soares said. "If, two years later, I unearthed new information about police officers implicated in the Amarildo case, it would still become a front-page headline with a full-page article. As the newspaper was primarily distributed at newsstands, scoops always took precedence over the regular news agenda – it was a way to set us apart from other newspapers."

Without contacts in the police or the justice system at the beginning of his career, Soares adopted a strategy that he continues to employ today: establishing close relationships with the families of crime victims and relying on them to gather information. Initially, he found this to be a relatively straightforward method for getting story ideas.

"If you went to the scene and started building relationships with people, you would often discover witnesses. It was the kind of story where you could compete with other reporters who had their own sources," he said.

Today, the reporter deems this approach crucial.

"To do investigative journalism concerning human rights violations, it is paramount to be close to the victims of violence. Understanding the dynamics within families enables you to recount the victims' stories. Many times, relatives also serve as witnesses, sometimes even the sole ones," Soares emphasized. "I frequently observe the media treating victims' relatives solely as family members, overlooking their role as crucial components in the investigations. That's a mistake."

Over time, other sources emerged, such as neighborhood associations, the Public Defender's Office, the Public Prosecutor's Office, and police stations. As he became better known, one source led to another, in what Soares describes as "a snowball effect." Regarding the police, Soares claims that "the very dynamics of the organization, where internal disputes exist," facilitates making contacts.

According to Soares, his current number of sources is not as high as it once was.

"There was a time in my life, around 2015 and 2016, when I constantly sought to build sources within the police. I liked to stop by the police station and have coffee with the detectives. They told me it was part of the profession, and I did it a lot," he recounted. "But there came a point when I stopped doing that, because you need a relationship of real trust, and I didn't feel that existed. Today, I have fewer sources, but I consider them better than before."

Another method that Soares regularly employs to gather information and scoops is through requests under the Access to Information Act (LAI). The legislation, passed in 2011, allows any person to request information produced by public entities. The journalist says he files information requests almost every week.

"The field of public security is one of the most fertile for information requests, which allow you to bypass limitations. You can access administrative information, information about promotions, or investigation results, for example. The entire first part of the book is based on this type of request," he explained.

Among the documents the journalist refers to are various records of incidents from when Ronnie Lessa, a former police officer now imprisoned and accused of murdering councilwoman Marielle Franco in 2018, was still serving in the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro. Soares kicks off both his book and the podcast "Pistoleiros" (Hitmen), from 2021, recounting how Lessa went from being a police officer known for bold and aggressive actions to being suspected of being a highly specialized contract killer.

The idea for the podcast – which was initially intended to be a written series for O Globo but evolved into an investigation consisting of five audio episodes at the suggestion of the newspaper's executives – emerged while Soares was writing a profile of Lessa. In his career, the journalist saw an example of a pattern and rotten structures within the organization.

"The guy was treated in the PM (Military Police) like a Robocop, and all of his incidents that ended in death, which in theory should have led to investigations, actually prompted praise and bonuses for bravery," Soares said. "So, I started thinking that I knew several stories like this. Stories of police officers who were treated as heroes but ended up going down the opposite path towards crime. And I wanted to demystify that."

As described in the early moments of "Pistoleiros" and as confirmed by authorities consulted by LJR, the former police officer conducted online searches for the journalist's name and address. According to the podcast, these searches, discovered through investigations by the federal police, happened in just one afternoon.

Soares has received more backlash for his reporting. For example, he says that one day he woke up to more than 1,500 messages insulting and threatening him on his WhatsApp. He said his phone number had been shared in groups of police officers and police supporters.

The journalist also said he has been subjected to lawsuits from police officers who are alleging defamation.

Another incident occurred on Dec. 9, 2020, when the then-spokeswoman of the Military Police of Rio, Lieutenant Colonel Gabryela Dantas, recorded a video attacking Soares.

At the time, the police officer responded to an article by Soares that concerned a Military Police unit under investigation for its alleged involvement in the murder of two children in the city of Duque de Caxias, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, and the increased use of ammunition for that unit.

In the video, Lieutenant-Colonel Dantas states that Soares' text is a “totally irresponsible conclusion, in addition to being completely false, it is cowardly and unscrupulous.” She said that Soares was “taking advantage of a national commotion to turn the population against the Military Police,” and asked anyone who watched it to share the video. After strong negative repercussions, she ended up being dismissed from her position.

Such incidents lead to two obvious questions: does Soares not fear retaliation for his investigations, and what precautions does he take in his daily life?

Regarding the second question, the journalist is succinct. He simply mentions that he is careful with his personal data, and, for example, does not share information about his personal life on social media.

As for fear, Soares says he "used to feel it a lot," but not anymore.

"This is a question I get asked all the time, but it's not something I usually think about. It's been 11 years working with this, and I've developed a thick skin. It's not something that crosses my mind when I'm about to publish a story," he said.

The fact that he works for O Globo, one of the largest newspapers in Brazil, provides protection against threats, he added.

"Whenever I've needed anything in this regard, whether it's institutional support or [fighting against] legal harassment, the newspaper has had my back. Covering what I cover while working independently might have been impossible, but O Globo is, in a way, a shield. Perhaps, if I were a freelancer or worked for a smaller or independent outlet, I would have a different answer," Soares said.

The journalist offers practical advice against intimidation:

"I would say that the best vaccine against this kind of thing is to be as transparent as possible in your work. I am the most transparent person possible; I call the lawyer, explain exactly what I want to do in the story, explain that I don't want to harm anyone, and describe how the article will come out," he said. "I don't like being in the position of 'enemy of the police,' I never sought that for myself. I have nothing against the police; on the contrary, my book is precisely an attempt to shed light on a problem that is little documented and little talked about."

The cover of the recently published book 'Milicianos: How agents trained to combat crime began to kill in its service' by Companhia das Letras in Brazil

Soares' work has garnered recognition in various forms. In December 2020, at the age of 29, O Globo promoted him to “special reporter,” considered the highest position attainable for reporters at Brazilian media outlets. In practice, this position offers better salaries and extensive freedom to pursue one's stories without the obligation to publish on a frequent basis.

In terms of awards, the journalist has already received more than 10, including the 2021 Kurt Schork Award organized by the Thomson Reuters Foundation in the "Local Reporter" category for his work covering public security and human rights in Rio de Janeiro.

Recognition also comes from the people with whom Soares learned during his formative years. Regarded by the reporter as one of his "idols" in the field of public security, economist Joana Monteiro, a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation, says that Soares, along with Bruno Paes Manso—a journalist who has ceased regular contributions to media outlets and now conducts research at the university—introduces new knowledge even to experts in the field.

"This investigative journalism work is extremely important. A significant portion of the work in the [public security] field has emerged from this logic of someone who is out in the street, collecting information little by little and piecing it together," Monteiro told LJR. "I haven't read the book yet, but I've listened to 'Pistoleiros,' and I think it is very good. It's not just a new summary of opinions; it introduces new elements and produces new insights. Doing this kind of reporting is not trivial. It takes brutal courage to do many of the things he has done, such as exposing cases of corruption and abuse of force."

Octavio Guedes, former editor-in-chief of Extra until 2017 and now a political commentator on GloboNews, speaks highly of his former subordinate.

"Since he arrived at Extra, Rafael caught the attention of editors for his broad perspective on security. The police reporter is typically assigned to cover one crime after another. In a city like Rio, where one tragedy supersedes the previous one, it takes intelligence and persistence to go beyond the daily crime coverage," he told LJR.

"This means reading the landscape, understanding the need for qualified law enforcement against crime, and addressing the topic of human rights from a journalistic perspective. Rafael, despite being young, had these qualities. That's why I consider him a public security reporter with a well-rounded perspective on all related subjects," he added.

Marcelo Pasqualetti, a personal friend of Soares and a Federal Police agent who served as a consultant on "Pistoleiros," finds it unfair that some police officers harbor antipathy toward Soares. He emphasizes that this sentiment is not universally shared within the police force.

"When I receive criticism, I see an opportunity for growth. But some people take offense, get upset, think that institutions are doing well or are above criticism," Pasqualetti told LJR. "But I think he [Soares] manages to point out flaws and continues to hang around successfully. Many people understand that it's not personal, that it's a critique that needs to be made for the growth of the institutions themselves. The criticism is directed at the institution."

In terms of the future, Soares said he is currently considering proposals to adapt "Milicianos" into documentary and fictional formats for television. The reporter also mentioned his involvement in a long-term investigation for O Globo, in addition to his routine work and publications in the newspaper and Extra.

Frequent publications, at least once or twice a month, are a habit that the journalist maintains even after his promotion to special reporter, a position that theoretically freed him from the need for incessant new articles.

"I like to keep publishing so that people can see that I continue to address these issues. I push myself to publish, both to stay connected to sources, because I know stories, and it's crucial not to overlook them," he said. "This work is also fundamental for me, because it forces me not to disconnect from the real world and everyday life, from what is happening. I also thrive on this routine.”

A substantial amount of the information the journalist hears or knows cannot be disclosed. He remembered that in 2015, he had already heard about former police officer Adriano da Nóbrega allegedly leading a group of hitmen but lacked sufficient evidence to publish this information. It wasn't until 2019, following Marielle's murder and a subsequent police investigation, that Nobrega's name surfaced in the newspaper.

A portrait of the late councilwoman Marielle Franco in the Maré favela, in Rio de Janeiro, in 2018, She's wearing earrings and a black dress with green and red details

Concerning the identity of the individual who ordered the murder of the councilwoman, one of Brazil's most perplexing unsolved mysteries, the journalist stated that he holds strong suspicions that he cannot share at this time. He hinted at the state of the investigation and expressed his belief that it will be resolved soon.

"The narrative surrounding the Marielle case has muddied the waters of what is real about the case," Soares said. "So I think that when investigators do reach conclusions, nobody will believe them because a narrative larger than the case itself has been created. This poses a challenge for the investigation: not only must they arrive at conclusions, but they also need to convince public opinion. However, I believe they will reach those conclusions soon. I am very optimistic."

As for the future of journalism as a whole, Soares said that investigative reporting is a way to overcome the crisis in the industry. In a more chaotic and polluted media environment, with a greater plurality of voices but also widespread disinformation, this is a way for the profession not to succumb, he stated.

"The press as a whole has lost relevance to the public. If we want to recover it, the way forward is by investing in investigation, investing in trying to uncover what others want to hide," Soares said.

In terms of public security in Rio de Janeiro, Soares said that over the past three decades, despite changes in government, the state's approach has remained unchanged, relying on a logic of confrontation and large-scale operations that have failed to effectively solve the problem.

According to Soares, the issue of police violence should be a central topic for debate during election campaigns, as it should be evident that the current policy "not only has been unable to truly address the security problem, but also feeds the workforce of organized crime."

Nevertheless, the journalist expresses optimism regarding the future of security in Rio. His reasoning, though intricate, is straightforward: for decades, public security policy in the state has overlooked the knowledge generated in the field, according to Soares. In this respect, evaluating its effectiveness is challenging because no serious attempt at change has ever been put into practice.

"Joana Monteiro says something that I strongly resonate w

ith: among all the evidence-based approaches we study in this field, none have been tested here. We've never implemented what academia produces—what comprises the best practices in the domain of public security. Therefore, there's still potential for the future. I'd be genuinely concerned if we had adopted these practices and they had all failed," Soares said.