With more than three decades of experience, Mexican television journalist Rafael Ortega has recorded the history of the disability movement in his country and in Latin America.

He entered media when it was still common to use medical terms to refer to people with disabilities (disabled, incapacitated, sick) and when the United Nations still did not have a Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Rafael Ortega conducts an interview. (Courtesy)

In 1988, when he was a journalism student at the Carlos Septíen García school, he was shot. Since then, he’s been in a wheelchair. He wanted to be a war correspondent, but he thinks that maybe he would have been hit instead in Nicaragua or the Middle East.

“I never imagined being locked in a newsroom in an office coordinating newscasts or writing as editor-in-chief. However, that was how my career began,” said Ortega, who started out in journalism on the news desk at the now defunct news agency Eco.

Ortega, who now works for Foro TV, is one of the few journalists with disabilities working in newsrooms in Latin America. In his storied career, he has covered the Parapan American Games 2011, the approval of legislation in favor of people with disabilities and the creation of the first bodies in charge of public policies in this sector.

Journalists do not escape the prejudices and stereotypes that surround disabilities. Although there are cases of reporters with disabilities inside Latin American newsrooms, they are the exception. There is no hard data on this topic, but anecdotal evidence points to this being the case.

To understand the barriers for journalists with disabilities who want to enter newsrooms, as well as the treatment of persons with disabilities in the media, LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) spoke with Ortega and other media professionals about their experience working in newsrooms and their advice for giving stories a human rights approach.

Breaking paradigms

This time, Ortega is sharing his story. More often, he is telling other people’s stories, with a focus on civil human rights organizations or the situation of people with disabilities in prison.

The journalist recognizes other experienced colleagues with disabilities, such as journalist Francisca Saavedra, who was director of international correspondents for Noticieros Televisa. With her, he produced the program “Retos” (Challenges), focused on the search for spaces and opportunities for people with disabilities.

Ortega emphasized the importance of visibility to Saavedra at the beginning of the program: “Television is for people who can contribute. You and I have to break those paradigms. I don't want them to make a television shot that is medium shot. I want the wheelchair to be seen.”

Con Francisca Saavedra, Ortega realizó el programa “Retos”, enfocado a la búsqueda de espacios y oportunidades de las personas con discapacidad. (Cortesia)

He remembered how decades ago it was common for the media to illustrate disability without including the diversity of this population, excluding people with intellectual and auditory disabilities, among others.

He insists that just talking about disability is not enough to appear in the media. It is necessary to have news, something new, he remarks.

"The media will not listen to you if you do not generate news, but not the mournful news, I insist; the news that is useful," he explained.

Like Ortega, Jorge Lanzagorta also adapted to his disability while in school, earning his bachelor’s degree in Communication at the Ibero-American University of Puebla, a state located in the center of Mexico.

“When I entered Ibero, it was the first day that I started using the cane. Throughout high school, I experienced a loss of vision, and when I entered the university, I experienced visual impairment in an educational environment,” Lanzargota, who writes for independent digital media outlet Lado B, told LJR.

It was at university where he learned more about the issue of media and access to information.

Mely Arellano, editor of Lado B, was his professor, and there the idea arose to start publishing in this media outlet, focused on human rights coverage.

One of his stories is "Without resources for the Institute of Disability, but the CRIT receives almost $55 million." CRIT, or Teletón Children's Rehabilitation and Inclusion Centers in English, is a controversial nonprofit organization backed by Televisa that aids children throughout Mexico who have neuromusculoskeletal disabilities.

"I began to explore the issue of resources, review how they were allocated by the State for this Institute. What was its plan?” In his journalistic investigation, he confirmed that the organization Teletón receives more funds than the public institute.

Lanzagorta described working in the newsroom like belonging to a community where "there is always collaboration and support in the process." Collective work at media outlet Lado B is something that allows him to work with confidence.

The journalist acknowledged that in processes in the newsroom that are not accessible to people with disabilities, there is openness at Lado B to solve problems. He explained that one of the most common barriers is the lack of accessibility in news websites. As an example he shared that it is common for there to be a lack of description on photographs for news items that he must monitor to make his reports.

Barriers to entering the newsroom

Ortega’s and Lanzagorta’s cases are the exception in a scenario where people with disabilities are often excluded from newsrooms, something that not only happens in Latin America, but also in the United States, as Sara Luterman wrote for NiemanLab.

“The only newspaper I worked for was the university newspaper,” Peruvian journalist Andrea Burga shared at the 1st Latin American Conference on Diversity in Journalism. The newspaper provided accessibility measures necessary to do her work because, as a blind person, she requires software that helps her read the screen and, in turn, write.

CW from top R: Andrea Medina, Andrea Burga and Verónica González speak at the

According to the journalist, traditional media in Peru refused to install this program and adapt the work equipment on the grounds that it would not be compatible with the newspaper's team.

"For this reason, I started personal projects based on independent journalism because in my country various media told me that they could not give me accessibility measures because they are not prepared for a blind person," said Burga, who is creator of the digital space Sociedad y Discapacidad (Sodis).

Andrea Medina, a journalist from Chile, also shared the complications of working in media newsrooms due to the so-called “attitudinal barriers,” that is, barriers in people’s ideas and prejudices.

“It is very difficult for them to give you those opportunities. I have had certain opportunities to work as a journalist in the media. I was able to do my professional internships in a newspaper with national circulation, in the area where I was trained, the area of economics, but I stopped working in digital media because I had a very long absence,” she said. “They could not wait for me to recover. You start to see those barriers.”

She shared that being a person with the condition Osteogenesis imperfecta, her recovery times after a fracture are different — something she said they did not understand in the newsroom.

Verónica González, who has a visual impairment, recalled the times she heard "you can't cover that." She explained that the main barrier is guessing what "they can or cannot do."

González said that it is important that newsrooms ask people with disabilities before assuming that they cannot do something.

Reporting on disabilities

Mexican journalist Jorge Lanzargota’s experience outside journalism, in the world of activism and high-performance sports, also allows him to see how coverage on disability is usually few and far between.

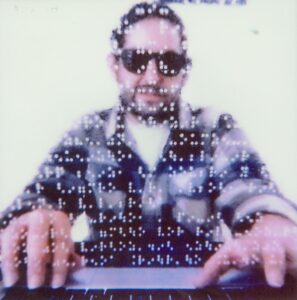

Journalist Jorge Lanzagorta at his keyboard (Courtesy)

For 11 years, he has directed “Fucho para ciegos,” a civil association of soccer for the blind. The sport has allowed him to be a high-performance athlete representing Mexico, winning a bronze medal at the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Paralympic Games.

He comments that one of the reasons why informative content on adapted sport is superficial is because of the so-called “disability myths” that treat these people as if they were heroes.

“Always dignifying the person, putting the person at the center,” is one of Lanzargota's recommendations for better reporting on people with disabilities and for including people with disabilities in newsrooms. His most important piece of advice: “To know people who live with different types of disabilities, and always the person-person approach is something that helps us a lot to get closer to the real experience "

Broadcast journalist Rafael Ortega repeats over and over again that coverage must abandon the focus of pity and that journalism must speak naturally and remove that veil of a specialized topic.

He insists that this is boring and that “we need to talk about the issue of people with disabilities as if it were routine because we are all exposed to a circumstance like this. One day I got up and at night, my life had taken a 180 degree turn.”

For more information and guidance on reporting on persons with disabilities, please see the Disability Language Style Guide, recently published in English and Spanish by the National Center on Disability and Journalism at Arizona State University in the U.S.